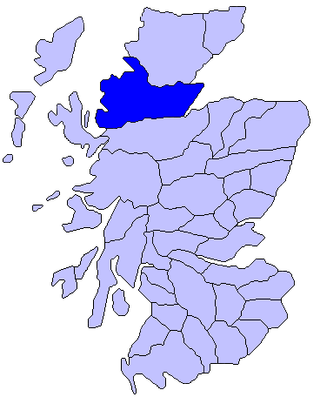

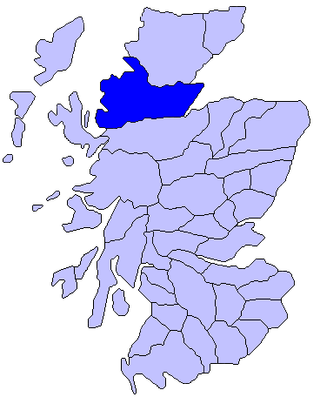

Ross is an area of Scotland. It was first recorded in the tenth century as a province. It was claimed by the Scottish crown in 1098, and from the 12th century Ross was an earldom. From 1661 there was a county of Ross, also known as Ross-shire, covering most but not all of the province, in particular excluding Cromartyshire. Cromartyshire was subsequently merged with the county of Ross in 1889 to form the county of Ross and Cromarty. The area is now part of the Highland council area.

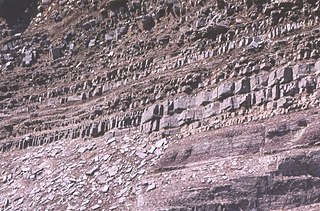

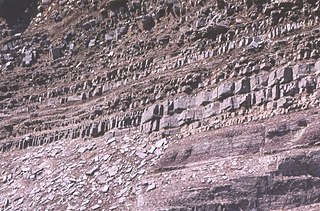

Liathach is a mountain in the Torridon Hills, in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. It stands between Loch Torridon and the neighbouring mountain Beinn Eighe. The mountain is a ridge running east–west, with several peaks, and its upper half is made up of many steep rocky terraces. The highest peak is the Munro of Spidean a' Choire Lèith at 1,055 metres (3,461 ft) high. The other Munro peak is Mullach an Rathain at 1,024 metres (3,360 ft) high.

The Torridon Hills surround Torridon village in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. The name is usually applied to the mountains to the north of Glen Torridon. They are among the most dramatic and spectacular peaks in the British Isles and made of some of the oldest rocks in the world. Many are over 3,000 feet high, so are considered Munros.

The Moine Thrust Belt or Moine Thrust Zone is a linear tectonic feature in the Scottish Highlands which runs from Loch Eriboll on the north coast 190 kilometres (120 mi) southwest to the Sleat peninsula on the Isle of Skye. The thrust belt consists of a series of thrust faults that branch off the Moine Thrust itself. Topographically, the belt marks a change from rugged, terraced mountains with steep sides sculptured from weathered igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rocks in the west to an extensive landscape of rolling hills over a metamorphic rock base to the east. Mountains within the belt display complexly folded and faulted layers and the width of the main part of the zone varies up to ten kilometres, although it is significantly wider on Skye.

The Northwest Highlands are located in the northern third of Scotland that is separated from the Grampian Mountains by the Great Glen. The region comprises Wester Ross, Assynt, Sutherland and part of Caithness. The Caledonian Canal, which extends from Loch Linnhe in the south-west, via Loch Ness to the Moray Firth in the north-east splits this area from the rest of the country. The city of Inverness and the town of Fort William serve as gateways to the region from the south.

The Stac Fada Member is a distinctive layer towards the top of the Mesoproterozoic Bay of Stoer Formation, part of the Stoer Group in northwest Scotland. This rock unit is generally 10 to 15 metres thick and is made of sandstone that contains accretionary lapilli and many dark green glassy fragments of mafic composition.

The Lewisian complex or Lewisian gneiss is a suite of Precambrian metamorphic rocks that outcrop in the northwestern part of Scotland, forming part of the Hebridean Terrane and the North Atlantic Craton. These rocks are of Archaean and Paleoproterozoic age, ranging from 3.0–1.7 billion years (Ga). They form the basement on which the Stoer Group, Wester Ross Supergroup and probably the Loch Ness Supergroup sediments were deposited. The Lewisian consists mainly of granitic gneisses with a minor amount of supracrustal rocks. Rocks of the Lewisian complex were caught up in the Caledonian orogeny, appearing in the hanging walls of many of the thrust faults formed during the late stages of this tectonic event.

The Hebridean terrane is one of the terranes that form part of the Caledonian orogenic belt in northwest Scotland. Its boundary with the neighbouring Northern Highland terrane is formed by the Moine Thrust Belt. The basement is formed by Archaean and Paleoproterozoic gneisses of the Lewisian complex, unconformably overlain by the Neoproterozoic Torridonian sediments, which in turn are unconformably overlain by a sequence of Cambro–Ordovician sediments. It formed part of the Laurentian foreland during the Caledonian continental collision.

The Unkar Group is a sequence of strata of Proterozoic age that are subdivided into five geologic formations and exposed within the Grand Canyon, Arizona, Southwestern United States. The Unkar Group is the basal formation of the Grand Canyon Supergroup. The Unkar is about 1,600 to 2,200 m thick and composed, in ascending order, of the Bass Formation, Hakatai Shale, Shinumo Quartzite, Dox Formation, and Cardenas Basalt. The Cardenas Basalt and Dox Formation are found mostly in the eastern region of Grand Canyon. The Shinumo Quartzite, Hakatai Shale, and Bass Formation are found in central Grand Canyon. The Unkar Group accumulated approximately between 1250 and 1104 Ma. In ascending order, the Unkar Group is overlain by the Nankoweap Formation, about 113 to 150 m thick; the Chuar Group, about 1,900 m (6,200 ft) thick; and the Sixtymile Formation, about 60 m (200 ft) thick. These are all of the units of the Grand Canyon Supergroup. The Unkar Group makes up approximately half of the thickness of the Grand Canyon Supergroup.

The Bass Formation, also known as the Bass Limestone, is a Mesoproterozoic rock formation that outcrops in the eastern Grand Canyon, Coconino County, Arizona. The Bass Formation erodes as either cliffs or stair-stepped cliffs. In the case of the stair-stepped topography, resistant dolomite layers form risers and argillite layers form steep treads. In general, the Bass Formation in the Grand Canyon region and associated strata of the Unkar Group-rocks dip northeast (10°–30°) toward normal faults that dip 60+° toward the southwest. This can be seen at the Palisades fault in the eastern part of the main Unkar Group outcrop area. In addition, thick, prominent, and dark-colored basaltic sills intrude across the Bass Formation.

The Shinumo Quartzite also known as the Shinumo Sandstone, is a Mesoproterozoic rock formation, which outcrops in the eastern Grand Canyon, Coconino County, Arizona,. It is the 3rd member of the 5-unit Unkar Group. The Shinumo Quartzite consists of a series of massive, cliff-forming sandstones and sedimentary quartzites. Its cliffs contrast sharply with the stair-stepped topography of typically brightly-colored strata of the underlying slope-forming Hakatai Shale. Overlying the Shinumo, dark green to black, fissile, slope-forming shales of the Dox Formation create a well-defined notch. It and other formations of the Unkar Group occur as isolated fault-bound remnants along the main stem of the Colorado River and its tributaries in Grand Canyon.

Typically, the Shinumo Quartzite and associated strata of the Unkar Group dip northeast (10°–30°) toward normal faults that dip 60+° toward the southwest. This can be seen at the Palisades fault in the eastern part of the main Unkar Group outcrop area.

The geology of the Isle of Skye in Scotland is highly varied and the island's landscape reflects changes in the underlying nature of the rocks. A wide range of rock types are exposed on the island, sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous, ranging in age from the Archaean through to the Quaternary.

The Dox Formation, also known as the Dox Sandstone, is a Mesoproterozoic rock formation that outcrops in the eastern Grand Canyon, Coconino County, Arizona. The Dox Formation comprises the bulk of the Unkar Group, the older subdivision of the Grand Canyon Supergroup. The Unkar Group is about 1,600 to 2,200 m thick and composed of, in ascending order, the Bass Formation, Hakatai Shale, Shinumo Quartzite, Dox Formation, and Cardenas Basalt. The Unkar Group is overlain in ascending order by the Nankoweap Formation, about 113 to 150 m thick; the Chuar Group, about 1,900 m (6,200 ft) thick; and the Sixtymile Formation, about 60 m (200 ft) thick. The entire Grand Canyon Supergroup overlies deeply eroded granites, gneisses, pegmatites, and schists that comprise Vishnu Basement Rocks.

The Sixtymile Formation is a very thin accumulation of sandstone, siltstone, and breccia underlying the Tapeats Sandstone that is exposed in only four places in the Chuar Valley. These exposures occur atop Nankoweap Butte and within Awatubi and Sixtymile Canyons in the eastern Grand Canyon, Arizona. The maximum preserved thickness of the Sixtymile Formation is about 60 m (200 ft). The actual depositional thickness of the Sixtymile Formation is unknown owing to erosion prior to deposition of the Tapeats Sandstone.

The Stoer Group is a sequence of Mesoproterozoic sedimentary rocks that outcrops on the peninsula of Stoer, near Assynt, Sutherland. The dominant lithology is sandstone with breccias and conglomerates developed near the base It is subdivided into three formations. It lies unconformably on the underlying Archaean to Paleoproterozoic age gneisses of the Lewisian complex and is in turn unconformably overlain by the Neoproterozoic Torridon Group.

The Sleat Group, which outcrops on the Sleat peninsula on Skye, underlies the Torridon Group conformably, but the relationship with the Stoer Group is nowhere exposed. It is presumed to have been deposited later than the Stoer Group, but possibly in a separate sub-basin. It is metamorphosed to greenschist facies and sits within the Kishorn Nappe, part of the Caledonian thrust belt, making its exact relationship to the other outcrops difficult to assess. The sequence consists of mainly coarse feldspathic sandstones deposited in a fluvial environment with some less common grey shales, probably deposited in a lacustrine environment.

The Torridonian is the informal name given to a sequence of Mesoproterozoic to Neoproterozoic sedimentary rocks that outcrop in a strip along the northwestern coast of Scotland and some parts of the Inner Hebrides from the Isle of Mull in the southwest to Cape Wrath in the northeast. They lie unconformably on the Archaean to Paleoproterozoic basement rocks of the Lewisian complex and unconformably beneath the Cambrian to Lower Ordovician rocks of the Ardvreck Group.

The Loch Ness Supergroup is one of the subdivisions of the Neoproterozoic sequence of sedimentary rocks in the Scottish Highlands. It is found everywhere in tectonic contact above the older Wester Ross Supergroup. It is thought to be unconformably overlain by the Cryogenian to Cambrian Dalradian Supergroup.

The Wester Ross Supergroup is one of the subdivisions of the Neoproterozoic sequence of sedimentary rocks in the Scottish Highlands. It lies unconformably on medium to high-grade metamorphic rocks and associated igneous rocks of the Archaean and Paleoproterozoic age Lewisian complex or locally over the Mesoproterozoic sedimentary rocks of the Stoer Group. The contact between the Wester Ross Supergroup and the next youngest of the Neoproterozoic sequences in the Scottish Highlands, the Loch Ness Supergroup, is everywhere a tectonic one.

The Morar Group is a sequence of Tonian sedimentary rocks that have been subjected to a series of tectonic and metamorphic events since their deposition. Originally interpreted to be lowest (oldest) part of a "Moine Supergroup", this sequence now forms part of the Wester Ross Supergroup. They lie unconformably on Archean to Paleoproterozoic basement of the Lewisian complex. The contact with the overlying Glenfinnan Group of the Loch Ness Supergroup is everywhere a tectonic one, formed by the Sgurr Beag Thrust or related structures.