In ontology, the theory of categories concerns itself with the categories of being: the highest genera or kinds of entities. To investigate the categories of being, or simply categories, is to determine the most fundamental and the broadest classes of entities. A distinction between such categories, in making the categories or applying them, is called an ontological distinction. Various systems of categories have been proposed, they often include categories for substances, properties, relations, states of affairs or events. A representative question within the theory of categories might articulate itself, for example, in a query like, "Are universals prior to particulars?"

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was a German philosopher and one of the most influential figures of German idealism and 19th-century philosophy. His influence extends across the entire range of contemporary philosophical topics, from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy, the philosophy of history, philosophy of art, philosophy of religion, and the history of philosophy.

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical idealism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, spirit, or consciousness; that reality is entirely a mental construct; or that ideas are the highest type of reality or have the greatest claim to being considered "real". Because there are different types of idealism, it is difficult to define the term uniformly.

In logic, the law of non-contradiction (LNC) states that contradictory propositions cannot both be true in the same sense at the same time, e. g. the two propositions "the house is white" and "the house is not white" are mutually exclusive. Formally, this is expressed as the tautology ¬(p ∧ ¬p). For example it is tautologous to say "the house is not both white and not white" since this results from putting "the house is white" in that formula, yielding "not ", then rewriting this in natural English. The law is not to be confused with the law of excluded middle which states that at least one of two propositions like "the house is white" and "the house is not white" holds.

Omnipotence is the quality of having unlimited power. Monotheistic religions generally attribute omnipotence only to the deity of their faith. In the monotheistic religious philosophy of Abrahamic religions, omnipotence is often listed as one of God's characteristics, along with omniscience, omnipresence, and omnibenevolence. The presence of all these properties in a single entity has given rise to considerable theological debate, prominently including the problem of evil, the question of why such a deity would permit the existence of evil. It is accepted in philosophy and science that omnipotence can never be effectively understood.

Truth or verity is the property of being in accord with fact or reality. In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as beliefs, propositions, and declarative sentences.

Dialectic, also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argumentation. Dialectic resembles debate, but the concept excludes subjective elements such as emotional appeal and rhetoric. It has its origins in ancient philosophy and continued to be developed in the Middle Ages.

Aristotelianism is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the social sciences under a system of natural law. It answers why-questions by a scheme of four causes, including purpose or teleology, and emphasizes virtue ethics. Aristotle and his school wrote tractates on physics, biology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theatre, music, rhetoric, psychology, linguistics, economics, politics, and government. Any school of thought that takes one of Aristotle's distinctive positions as its starting point can be considered "Aristotelian" in the widest sense. This means that different Aristotelian theories may not have much in common as far as their actual content is concerned besides their shared reference to Aristotle.

In most contexts, the concept of good denotes the conduct that should be preferred when posed with a choice between possible actions. Good is generally considered to be the opposite of evil and is of ethics, morality, philosophy, and religion. The specific meaning and etymology of the term and its associated translations among ancient and contemporary languages show substantial variation in its inflection and meaning, depending on circumstances of place and history, or of philosophical or religious context.

The Critique of Pure Reason is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was followed by his Critique of Practical Reason (1788) and Critique of Judgment (1790). In the preface to the first edition, Kant explains that by a "critique of pure reason" he means a critique "of the faculty of reason in general, in respect of all knowledge after which it may strive independently of all experience" and that he aims to decide on "the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics".

Bernard Bosanquet was an English philosopher and political theorist, and an influential figure on matters of political and social policy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work influenced but was later subject to criticism by many thinkers, notably Bertrand Russell, John Dewey, William James and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Bernard was the husband of Helen Bosanquet, the leader of the Charity Organisation Society.

In semiotics, a sign is anything that communicates a meaning that is not the sign itself to the interpreter of the sign. The meaning can be intentional, as when a word is uttered with a specific meaning, or unintentional, as when a symptom is taken as a sign of a particular medical condition. Signs can communicate through any of the senses, visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, or taste.

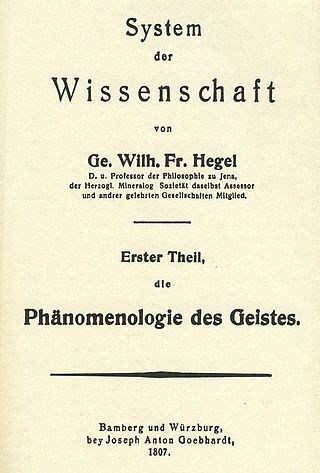

The Phenomenology of Spirit is the most widely discussed philosophical work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel; its German title can be translated as either The Phenomenology of Spirit or The Phenomenology of Mind. Hegel described the work, published in 1807, as an "exposition of the coming to be of knowledge". This is explicated through a necessary self-origination and dissolution of "the various shapes of spirit as stations on the way through which spirit becomes pure knowledge".

Summum bonum is a Latin expression meaning the highest or ultimate good, which was introduced by the Roman philosopher Cicero to denote the fundamental principle on which some system of ethics is based — that is, the aim of actions, which, if consistently pursued, will lead to the best possible life. Since Cicero, the expression has acquired a secondary meaning as the essence or ultimate metaphysical principle of Goodness itself, or what Plato called the Form of the Good. These two meanings do not necessarily coincide. For example, Epicurean and Cyrenaic philosophers claimed that the 'good life' consistently aimed for pleasure, without suggesting that pleasure constituted the meaning or essence of Goodness outside the ethical sphere. In De finibus, Cicero explains and compares the ethical systems of several schools of Greek philosophy, including Stoicism, Epicureanism, Aristotelianism and Platonism, based on how each defines the ethical summum bonum differently.

Representation is the use of signs that stand in for and take the place of something else. It is through representation that people organize the world and reality through the act of naming its elements. Signs are arranged in order to form semantic constructions and express relations.

Romanian philosophy is a name covering either:

Charles Sanders Peirce began writing on semiotics, which he also called semeiotics, meaning the philosophical study of signs, in the 1860s, around the time that he devised his system of three categories. During the 20th century, the term "semiotics" was adopted to cover all tendencies of sign researches, including Ferdinand de Saussure's semiology, which began in linguistics as a completely separate tradition.

Western philosophy refers to the philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word philosophy itself originated from the Ancient Greek philosophía (φιλοσοφία), literally, "the love of wisdom" Ancient Greek: φιλεῖν phileîn, "to love" and σοφία sophía, "wisdom".

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, understood as a project of independent philosophical inquiry, began in Baghdad, in the middle of the 8th century, and in France and Germany, in the itinerant court of Charlemagne in Aachen, in the last quarter of the 8th century. It is defined partly by the process of rediscovering the ancient culture developed in Greece and Rome during the Classical period, and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate sacred doctrine with secular learning. This is one of the defining characteristics in this time period. Understanding God was the focal point of study of the philosophers at that time, Muslim and Christian alike.

The following is a list of the major events in the history of German idealism, along with related historical events.