The 2008 Pacific typhoon season was a below average season which featured 22 named storms, eleven typhoons, and two super typhoons. The season had no official bounds; it ran year-round in 2008, but most tropical cyclones tend to form in the northwestern Pacific Ocean between May and November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northwestern Pacific Ocean.

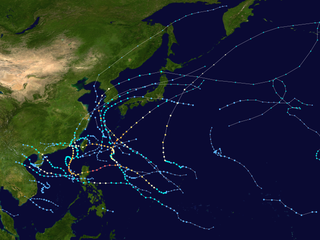

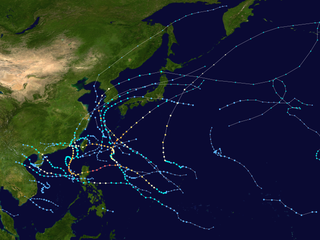

The 2012 Pacific typhoon season was a slightly above average season that produced 25 named storms, fourteen typhoons, and four intense typhoons. It was a destructive and the second consecutive year to be the deadliest season, primarily due to Typhoon Bopha which killed 1,901 people in the Philippines. It was an event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation, in which tropical cyclones form in the western Pacific Ocean. The season ran throughout 2012, though most tropical cyclones typically develop between May and October. The season's first named storm, Pakhar, developed on March 28, while the season's last named storm, Wukong, dissipated on December 29. The season's first typhoon, Guchol, reached typhoon status on June 15, and became the first super typhoon of the year on June 17.

Typhoon Kujira, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Dante, was first reported by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) on April 28. It was the fourth depression and the first typhoon of the season. The disturbance dissipated later that day however it regenerated early on April 30 within the southern islands of Luzon. It was then designated as a Tropical Depression during the next morning by the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), with PAGASA assigning the name Dante to the depression. However the JTWC did not designate the system as a depression until early on May 2 which was after the depression had made landfall on the Philippines. Later that day Dante was upgraded to a Tropical Storm and was named as Kujira by the JMA. The cyclone started to rapidly intensify becoming a typhoon early on May 4, and then reaching its peak winds of 155 km/h (100 mph) (10-min), 215 km/h (135 mph) (1-min) later that day after a small clear eye had developed.

The 2013 Pacific typhoon season was a devastating and catastrophic season that was the most active since 2004, and the deadliest since 1975. It featured Typhoon Haiyan, one of the most powerful storms in history, as well as one of the strongest to make landfall on record. It featured 31 named storms, 13 typhoons, and five super typhoons. The season's first named storm, Sonamu, developed on January 4 while the season's last named storm, Podul, dissipated on November 15. Collectively, the storms caused 6,829 fatalities, while total damage amounted to at least $26.41 billion (USD), making it, at the time, the costliest Pacific typhoon season on record, until it was surpassed five years later. As of 2024, it is currently ranked as the fifth-costliest typhoon season.

The 2015 Pacific typhoon season was a slightly above average season that produced twenty-seven tropical storms, eighteen typhoons, and nine super typhoons. The season ran throughout 2015, though most tropical cyclones typically develop between May and November. The season's first named storm, Mekkhala, developed on January 15, while the season's last named storm, Melor, dissipated on December 17. The season saw at least one named tropical system forming in each of every month, the first time since 1965. Similar to the previous season, this season saw a high number of super typhoons. Accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) during 2015 was extremely high, the third highest since 1970, and the 2015 ACE has been attributed in part to anthropogenic warming, and also the 2014-16 El Niño event, that led to similarly high ACE values in the East Pacific.

The 2016 Pacific typhoon season is considered to have been the fourth-latest start for a Pacific typhoon season since reliable records began. It was an average season, with a total of 26 named storms, 13 typhoons, and six super typhoons. The season ran throughout 2016, though typically most tropical cyclones develop between May and October. The season's first named storm, Nepartak, developed on July 3, while the season's last named storm, Nock-ten, dissipated on December 28.

The 2017 Pacific typhoon season was a below-average season in terms of accumulated cyclone energy and the number of typhoons and super typhoons, and the first since the 1977 season to not produce a Category 5-equivalent typhoon on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The season produced a total of 27 named storms, 11 typhoons, and only two super typhoons, making it an average season in terms of storm numbers. It was an event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation, in which tropical cyclones form in the western Pacific Ocean. The season runs throughout 2017, though most tropical cyclones typically develop between May and October. The season's first named storm, Muifa, developed on April 25, while the season's last named storm, Tembin, dissipated on December 26. This season also featured the latest occurrence of the first typhoon of the year since 1998, with Noru reaching this intensity on July 23.

The 2018 Pacific typhoon season was at the time, the costliest Pacific typhoon season on record, until the record was beaten by the following year. The season was well above-average, producing twenty-nine storms, thirteen typhoons, seven super typhoons and six Category 5 tropical cyclones. The season ran throughout 2018, though most tropical cyclones typically develop between May and October. The season's first named storm, Bolaven, developed on January 3, while the season's last named storm, Man-yi, dissipated on November 28. The season's first typhoon, Jelawat, reached typhoon status on March 29, and became the first super typhoon of the year on the next day.

The 2019 Pacific typhoon season was a devastating season that became the costliest on record, just ahead of the previous year and 2023, mainly due to the catastrophic damage wrought by typhoons Lekima, Faxai, and Hagibis. The season was the fifth and final consecutive to have above average tropical cyclone activity that produced a total of 29 named storms, 17 typhoons, and 5 super typhoons. The season's first named storm, Pabuk, reached tropical storm status on January 1, becoming the earliest-forming tropical storm of the western Pacific Ocean on record, breaking the previous record that was held by Typhoon Alice in 1979. The season's first typhoon, Wutip, reached typhoon status on February 20. Wutip further intensified into a super typhoon on February 23, becoming the strongest February typhoon on record, and the strongest tropical cyclone recorded in February in the Northern Hemisphere. The season's last named storm, Phanfone, dissipated on December 29 after it made landfall in the Philippines.

This timeline documents all of the events of the 2010 Pacific typhoon season. Most of the tropical cyclones forming between May and November. The scope of this article is limited to the Pacific Ocean, north of the equator between 100°E and the International Date Line. Tropical storms that form in the entire Western Pacific basin are assigned a name by the Japan Meteorological Agency. Tropical depressions that form in this basin are given a number with a "W" suffix by the United States' Joint Typhoon Warning Center. In addition, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) assigns names to tropical cyclones that enter or form in the Philippine area of responsibility. These names, however, are not in common use outside of the Philippines.

Severe Tropical Storm Rumbia, known in the Philippines as Tropical Storm Gorio, was a tropical cyclone that brought widespread flooding in areas of the Philippines and China late June and early July 2013. The sixth internationally named storm of the season, Rumbia formed from a broad area of low pressure situated in the southern Philippine Sea on June 27. Steadily organizing, the initial tropical depression moved towards the northwest as the result of a nearby subtropical ridge. On June 28, the disturbance strengthened to tropical storm strength, and subsequently made its first landfall on Eastern Samar in the Philippines early the following day. Rumbia spent roughly a day moving across the archipelago before emerging into the South China Sea. Over open waters, Rumbia resumed strengthening, and reached its peak intensity with winds of 95 km/h (50 mph) on July 1, ranking it as a severe tropical storm. The tropical cyclone weakened slightly before moving ashore the Leizhou Peninsula late that day. Due to land interaction, Rumbia quickly weakened into a low pressure area on July 2 and eventually dissipated soon afterwards.

This timeline documents all of the events of the 2012 Pacific typhoon season. The scope of this article is limited to the Pacific Ocean, north of the equator between 100°E and the International Date Line. During the season, 34 systems were designated as tropical depressions by either the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC), or other National Meteorological and Hydrological Services such as the China Meteorological Administration and the Hong Kong Observatory. Since the JMA runs the Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre (RSMC) for the Western Pacific, they assigned names to tropical depressions which developed into tropical storms in the basin. PAGASA also assigned local names to systems which are active in their area of responsibility; however, these names are not in common use outside of the Philippines.

Typhoon Hagupit known in the Philippines as Super Typhoon Ruby, was the second most intense tropical cyclone in 2014. Hagupit particularly impacted the Philippines in early December while gradually weakening, killing 18 people and causing $114 million of damage in the country. Prior to making landfall, Hagupit was considered the worst threat to the Philippines in 2014, but it was significantly smaller than 2013's Typhoon Haiyan.

This timeline documents all of the events of the 2015 Pacific typhoon season. Most of the tropical cyclones formed between May and November. The scope of this article is limited to the Pacific Ocean, north of the equator between 100°E and the International Date Line. This area, called the Western Pacific basin, is the responsibility of the Japanese Meteorological Agency (JMA). They host and operate the Regional Specialized Meteorological Center (RSMC), located in Tokyo. The Japanese Meteorological Agency (JMA) is also responsible for assigning names to all tropical storms that are formed within the basin. However, any storm that enters or forms in the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) will be named by the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) using a local name. Also of note - the Western Pacific basin is monitored by the United States' Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC), which gives all Tropical depressions a number with a "W" suffix.

The 2021 Pacific typhoon season was the second consecutive season to have below average tropical cyclone activity, with twenty-two named storms, and was the least active since 2011. Nine became typhoons, and five of those intensified into super typhoons. This low activity was caused by a strong La Niña that had persisted from the previous year. The season's first named storm, Dujuan, developed on February 16, while the last named storm, Rai, dissipated on December 21. The season's first typhoon, Surigae, reached typhoon status on April 16. It became the first super typhoon of the year on the next day, also becoming the strongest tropical cyclone in 2021. Surigae was also the most powerful tropical cyclone on record in the Northern Hemisphere for the month of April. Typhoons In-fa and Rai are responsible for more than half of the total damage this season, adding up to a combined total of $2.02 billion.

The 2022 Pacific typhoon season was the third consecutive season to have below average tropical cyclone activity, with twenty-five named storms forming. Of the tropical storms, ten became typhoons, and three would intensify into super typhoons. The season saw near-average activity by named storm count, although many of the storms were weak and short-lived, particularly towards the end of the season. This low activity was caused by an unusually strong La Niña that had persisted from 2020. The season's first named storm, Malakas, developed on April 6, while the last named storm, Pakhar, dissipated on December 12. The season's first typhoon, Malakas, reached typhoon status on April 12. The season ran throughout 2022, though most tropical cyclones typically develop between May and October. Tropical storms Megi and Nalgae were responsible for more than half of the casualties, while typhoons Hinnamnor and Nanmadol both caused $1 billion in damages.

The 2023 Pacific typhoon season was the fourth and final consecutive below-average season and became the third-most inactive typhoon season on record in terms of named storms, with just 17 named storms developing, only ahead of 2010 and 1998. Despite the season occurring during an El Niño event, which typically favors activity in the basin, activity was abnormally low. This was primarily due to a consistent period of negative PDO, which typically discourages tropical storm formation in this basin. The season was less active than the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season in terms of named storms, the fourth such season on record, after 2005, 2010 and 2020. The season's number of storms also did not exceed that of the 2023 Pacific hurricane season. Only ten became typhoons, with four strengthening further into super typhoons. However, it was very destructive, primarily due to Typhoon Doksuri which devastated the northern Philippines, Taiwan, and China in July, becoming the costliest typhoon on record as well as the costliest typhoon to hit mainland China, and Typhoon Haikui in September, which devastated China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. The season was less active in Southeast Asia, with no tropical storm making landfall in mainland Vietnam.

Tropical Depression Josie was a weak tropical system that impacted the Philippine archipelago of Luzon in July 2018, bringing widespread flooding. The tropical depression was classified in the South China Sea on July 20, and steadily moved eastward while gradually intensifying. The storm reached its peak intensity of 1-minute sustained winds of 65 km/h while nearing the northern tip of the Ilocos Region. By July 22, the system moved northward and rapidly weakened. The system was last noted on July 23 to the northeast of Taiwan.

The 2024 Pacific typhoon season was the fifth-latest starting Pacific typhoon season on record. It was average in terms of activity, and ended a four year streak of below average seasons that started in 2020. It was also the deadliest season since 2013, and became the fourth-costliest Pacific typhoon season on record, mostly due to Typhoon Yagi. This season saw an unusually active November, with the month seeing four simultaneously active named storms. The season runs throughout 2024, though most tropical cyclones typically develop between May and October. The season's first named storm, Ewiniar, developed on May 25, and eventually intensified into the first typhoon of the season, while the last named storm, Pabuk, dissipated on December 26. This season was an event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation in the western Pacific Ocean.

Typhoon Prapiroon, known in the Philippines as Severe Tropical Storm Florita, was a Category 1 typhoon that worsened the floods in Japan and also caused impacts in neighboring South Korea. The storm formed from an area of low pressure near the Philippines and strengthened to a typhoon before entering the Sea of Japan. The seventh named storm and the first typhoon of the annual annual typhoon season. Prapiroon originated from a low-pressure area far off the coast of Northern Luzon on June 28. Tracking westwards, it rapidly upgraded into a tropical storm, receiving the name Prapiroon due to favorable conditions in the Philippine Sea on the next day.