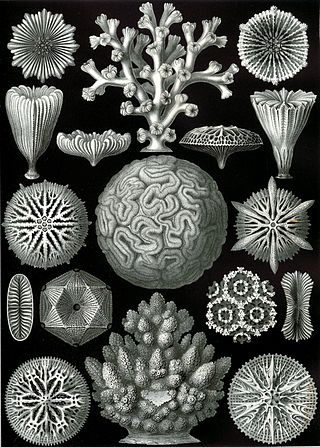

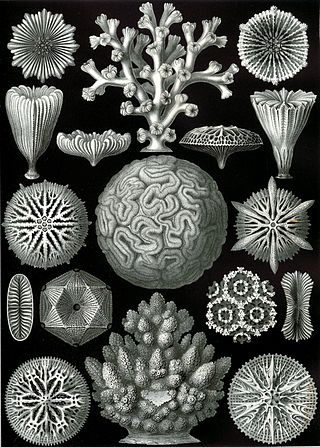

Anthozoa is a subphylum of marine invertebrates which includes sessile cnidarians such as the sea anemones, stony corals, soft corals and sea pens. Adult anthozoans are almost all attached to the seabed, while their larvae can disperse as planktons. The basic unit of the adult is the polyp; this consists of a cylindrical column topped by a disc with a central mouth surrounded by tentacles. Sea anemones are mostly solitary, but the majority of corals are colonial, being formed by the budding of new polyps from an original, founding individual. Colonies are strengthened by calcium carbonate and other materials and take various massive, plate-like, bushy or leafy forms.

Scleractinia, also called stony corals or hard corals, are marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria that build themselves a hard skeleton. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a mouth is fringed with tentacles. Although some species are solitary, most are colonial. The founding polyp settles and starts to secrete calcium carbonate to protect its soft body. Solitary corals can be as much as 25 cm (10 in) across but in colonial species the polyps are usually only a few millimetres in diameter. These polyps reproduce asexually by budding, but remain attached to each other, forming a multi-polyp colony of clones with a common skeleton, which may be up to several metres in diameter or height according to species.

Lophelia pertusa, the only species in the genus Lophelia, is a cold-water coral that grows in the deep waters throughout the North Atlantic ocean, as well as parts of the Caribbean Sea and Alboran Sea. Although L. pertusa reefs are home to a diverse community, the species is extremely slow growing and may be harmed by destructive fishing practices, or oil exploration and extraction.

Millepora dichotoma, the net fire coral, is a species of hydrozoan, consisting of a colony of polyps with a calcareous skeleton.

Oculina varicosa, or the ivory bush coral, is a scleractinian deep-water coral primarily found at depths of 70-100m, and ranges from Bermuda and Cape Hatteras to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. Oculina varicosa flourishes at the Oculina Bank off the east coast of Florida, where coral thickets house a variety of marine organisms. The U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service considers Oculina a genus of concern, due to the threat of rapid ocean warming. Species of concern are those species about which the U.S. Government's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Marine Fisheries Service, has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to indicate a need to list the species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA). While Oculina is considered a more robust genus in comparison to tropical corals, rising ocean temperatures continue to threaten coral health across the planet.

Madrepora oculata, also called zigzag coral, is a stony coral that is found worldwide outside of the polar regions, growing in deep water at depths of 50 to at least 1500 meters. It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae. It is one of only 12 species of coral that are found worldwide, including in Subantarctic oceans. In some areas, such as in the Mediterranean Sea and the Northeast Atlantic Ocean, it dominates communities of coral. Due to their similar distribution and taxonomic relationship, M. oculata is often experimentally compared to related deep sea coral, Lophelia pertusa.

Tubastraea, also known as sun coral or sun polyps, is a genus of coral in the phylum Cnidaria. It is a cup coral in the family Dendrophylliidae.

Coral aquaculture, also known as coral farming or coral gardening, is the cultivation of corals for commercial purposes or coral reef restoration. Aquaculture is showing promise as a tool for restoring coral reefs, which are dying off around the world. The process protects young corals while they are most at risk of dying. Small corals are propagated in nurseries and then replanted on the reef.

Porites lobata, known by the common name lobe coral, is a species of stony coral in the family Poritidae. It is found growing on coral reefs in tropical parts of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Millepora alcicornis, or sea ginger, is a species of colonial fire coral with a calcareous skeleton. It is found on shallow water coral reefs in the tropical west Atlantic Ocean. It shows a variety of different morphologies depending on its location. It feeds on plankton and derives part of its energy requirements from microalgae found within its tissues. It is an important member of the reef building community and subject to the same threats as other corals. It can cause painful stings to unwary divers.

Orange cup coral belongs to a group of corals known as large-polyp stony corals. This non-reef building coral extends beautiful translucent tentacles at night. Tubastraea coccinea is heterotrophic and does not contain zooxanthellae in its tissues as many tropical corals do, allowing it to grow in complete darkness as long as it can capture enough food.

Pocillopora damicornis, commonly known as the cauliflower coral or lace coral, is a species of stony coral in the family Pocilloporidae. It is native to tropical and subtropical parts of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Dipsastraea speciosa is a species of colonial stony coral in the family Merulinidae. It is found in tropical waters of the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Carijoa riisei, the snowflake coral or branched pipe coral, is a species of soft coral in the family Clavulariidae. It was originally thought to have been native to the tropical western Atlantic Ocean and subsequently spread to other areas of the world such as Hawaii and the greater tropical Pacific, where it is regarded as an invasive species. The notion that it is native to the tropical western Atlantic was perpetuated from the fact that the type specimen, described by Duchassaing & Michelotti in 1860, was collected from the US Virgin Islands. It has subsequently been shown through molecular evidence that it is more likely that the species is in fact native to the Indo-Pacific and subsequently spread to the western tropical Atlantic most likely as a hull fouling species prior to its original description.

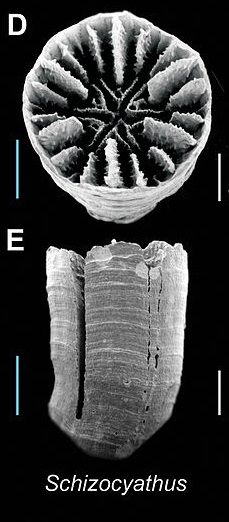

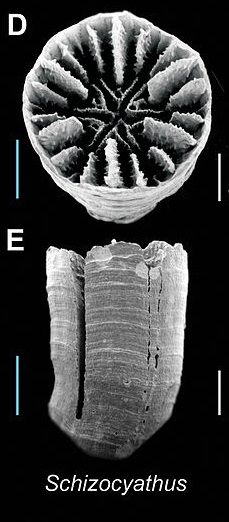

Schizocyathus is a monotypic genus of stony corals in the family Schizocyathidae, the only species being Schizocyathus fissilis. It is a deep water, azooxanthellate coral.

Polycyathus muellerae is a small species of coral in the family Caryophylliidae in the order Scleractinia, the stony corals. It is native to the northeastern Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. It is a large polyp, colonial coral and grows under overhangs and in caves as part of an assemblage of organisms suited to these poorly-lit sites.

Euphylliidae are known as a family of polyped stony corals under the order Scleractinia.

Oxypora glabra is a species of large polyp stony coral in the family Lobophylliidae. It is a colonial coral with thin encrusting laminae. It is native to the central Indo-Pacific.

Tubastraea faulkneri, common name Orange sun coral, is a species of large-polyp stony corals belonging to the family Dendrophylliidae. Other common names of this coral are Orange Cup Coral, Sun Coral, Orange Polyp Coral, Rose Sun Coral, Golden Cup Coral, Sun Flower Coral, and Tube Coral.

Tubastraea tagusensis is a hard coral species in the family Dendrophylliidae. The species is azooxanthellate, thus does not need sunlight for development, and does not form reefs. It is native to the Galapagos Islands but has become invasive along the Atlantic coast of South America.