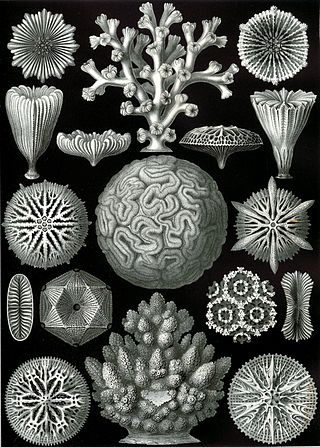

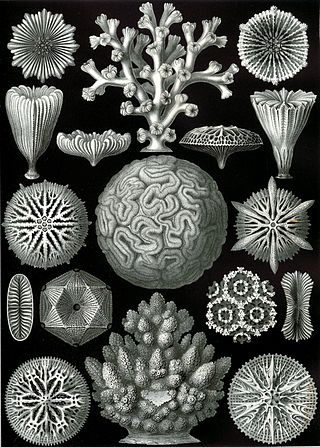

Anthozoa is a subphylum of marine invertebrates which includes sessile cnidarians such as the sea anemones, stony corals, soft corals and sea pens. Adult anthozoans are almost all attached to the seabed, while their larvae can disperse as planktons. The basic unit of the adult is the polyp; this consists of a cylindrical column topped by a disc with a central mouth surrounded by tentacles. Sea anemones are mostly solitary, but the majority of corals are colonial, being formed by the budding of new polyps from an original, founding individual. Colonies are strengthened by calcium carbonate and other materials and take various massive, plate-like, bushy or leafy forms.

Scleractinia, also called stony corals or hard corals, are marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria that build themselves a hard skeleton. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a mouth is fringed with tentacles. Although some species are solitary, most are colonial. The founding polyp settles and starts to secrete calcium carbonate to protect its soft body. Solitary corals can be as much as 25 cm (10 in) across but in colonial species the polyps are usually only a few millimetres in diameter. These polyps reproduce asexually by budding, but remain attached to each other, forming a multi-polyp colony of clones with a common skeleton, which may be up to several metres in diameter or height according to species.

Elkhorn coral is an important reef-building coral in the Caribbean. The species has a complex structure with many branches which resemble that of elk antlers; hence, the common name. The branching structure creates habitat and shelter for many other reef species. Elkhorn coral is known to grow quickly with an average growth rate of 5 to 10 cm per year. They can reproduce both sexually and asexually, though asexual reproduction is much more common and occurs through a process called fragmentation.

Pavona duerdeni, the porkchop coral, is a coral that forms clusters of cream-colored lobes or discs. They grow in large colonies, divided into ridges or hillocks. The coral is considered to be uncommon due to its low confirmed abundance, yet they are more commonly found in Hawaii, the Indo-Pacific, and the Tropical Eastern Pacific. They make up some of the largest colonies of corals, and have a slow growth rate, as indicated by their dense skeletons. Their smooth appearance is due to their small corallites growing on their surface.

Coral aquaculture, also known as coral farming or coral gardening, is the cultivation of corals for commercial purposes or coral reef restoration. Aquaculture is showing promise as a tool for restoring coral reefs, which are dying off around the world. The process protects young corals while they are most at risk of dying. Small corals are propagated in nurseries and then replanted on the reef.

Galaxea fascicularis is a species of colonial stony coral in the family Euphylliidae, commonly known as Octopus coral, Fluorescence grass coral, and Galaxy coral among various vernacular names.

Millepora alcicornis, or sea ginger, is a species of colonial fire coral with a calcareous skeleton. It is found on shallow water coral reefs in the tropical west Atlantic Ocean. It shows a variety of different morphologies depending on its location. It feeds on plankton and derives part of its energy requirements from microalgae found within its tissues. It is an important member of the reef building community and subject to the same threats as other corals. It can cause painful stings to unwary divers.

Umimayanthus parasiticus, commonly known as the sponge zoanthid, is a species of coral in the order Zoantharia which grows symbiotically on several species of sponge. It is found in shallow waters in the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico.

Millepora platyphylla is a species of fire coral, a type of hydrocoral, in the family Milleporidae. It is also known by the common names blade fire coral and plate fire coral. It forms a calcium carbonate skeleton and has toxic, defensive polyps that sting. It obtains nutrients by consuming plankton and via symbiosis with photosynthetic algae. The species is found from the Red Sea and East Africa to northern Australia and French Polynesia. It plays an important role in reef-building in the Indo-Pacific region. Depending on its environment, it can have a variety of different forms and structures.

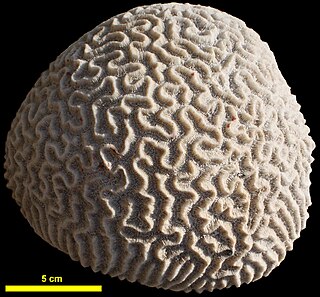

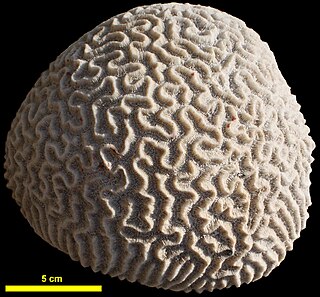

Pseudodiploria strigosa, the symmetrical brain coral, is a colonial species of stony coral in the family Mussidae. It occurs on reefs in shallow water in the West Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. It grows slowly and lives to a great age.

Pseudodiploria clivosa, the knobby brain coral, is a colonial species of stony coral in the family Mussidae. It occurs in shallow water in the West Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea.

Mussa is a genus of stony coral in the family Faviidae. It is monotypic, being represented by the single species Mussa angulosa, commonly known as the spiny or large flower coral. It is found on reefs in shallow waters in the Caribbean Sea, the Bahamas and the Gulf of Mexico.

Cynarina lacrymalis is a species of stony coral in the family Lobophylliidae. It is variously known as the flat cup coral, solitary cup coral, button coral, doughnut coral, or cat's eye coral. It is found in the western Indo-Pacific Ocean and is sometimes kept in reef aquaria.

Orange cup coral belongs to a group of corals known as large-polyp stony corals. This non-reef building coral extends beautiful translucent tentacles at night. Tubastraea coccinea is heterotrophic and does not contain zooxanthellae in its tissues as many tropical corals do, allowing it to grow in complete darkness as long as it can capture enough food.

Catalaphyllia is a monotypic genus of stony coral in the family Euphylliidae from the western Pacific Ocean. It is represented by a single species, Catalaphyllia jardinei, commonly known as elegance coral. It was first described by William Saville-Kent in 1893 as Pectinia jardinei.

Millepora complanata, commonly known as blade fire coral, is a species of fire coral in the family Milleporidae. It is found in shallow waters in the Caribbean Sea where it is a common species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed its conservation status as being critically endangered.

Porites cylindrica, commonly known as Hump coral, is a stony coral belonging to the subclass Hexacorallia in the class Anthozoa. Hexacorallia differ from other subclasses in that they have six or fewer axes of symmetry. Members of this class possess colonial polyps which can be reef-building, secreting a calcium carbonate skeleton. They are dominant in both inshore reefs and midshelf reefs.

Euphylliidae are known as a family of polyped stony corals under the order Scleractinia.

Tubastraea faulkneri, common name Orange sun coral, is a species of large-polyp stony corals belonging to the family Dendrophylliidae. Other common names of this coral are Orange Cup Coral, Sun Coral, Orange Polyp Coral, Rose Sun Coral, Golden Cup Coral, Sun Flower Coral, and Tube Coral.

Tubastraea micranthus, commonly known as the Black sun coral, is a coral from the Tubastraea genus, which comprises the sun corals. They have a dark green color and they grow and branch out in bush/tree like colonies. The habitat of T. micranthus ranges from the Red Sea to Madagascar, and into the Pacific as far as Fiji. It has been observed in waters as shallow as 4m to a depth of 138m in the new habitat. It is notable though, that in its native habitats Tubastraea micranthus has only been found at depths up to 50 meters and any discovered at lower depths are in invasive environments. Furthermore, there have been obscure sightings of Tubastraea micranthus in Korea.