The Prandtl number (Pr) or Prandtl group is a dimensionless number, named after the German physicist Ludwig Prandtl, defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity. The Prandtl number is given as:

In thermal fluid dynamics, the Nusselt number is the ratio of convective to conductive heat transfer at a boundary in a fluid. Convection includes both advection and diffusion (conduction). The conductive component is measured under the same conditions as the convective but for a hypothetically motionless fluid. It is a dimensionless number, closely related to the fluid's Rayleigh number.

In fluid mechanics, the Rayleigh number (Ra, after Lord Rayleigh) for a fluid is a dimensionless number associated with buoyancy-driven flow, also known as free (or natural) convection. It characterises the fluid's flow regime: a value in a certain lower range denotes laminar flow; a value in a higher range, turbulent flow. Below a certain critical value, there is no fluid motion and heat transfer is by conduction rather than convection. For most engineering purposes, the Rayleigh number is large, somewhere around 106 to 108.

The kinetic theory of gases is a simple, historically significant classical model of the thermodynamic behavior of gases, with which many principal concepts of thermodynamics were established. The model describes a gas as a large number of identical submicroscopic particles, all of which are in constant, rapid, random motion. Their size is assumed to be much smaller than the average distance between the particles. The particles undergo random elastic collisions between themselves and with the enclosing walls of the container. The basic version of the model describes the ideal gas, and considers no other interactions between the particles.

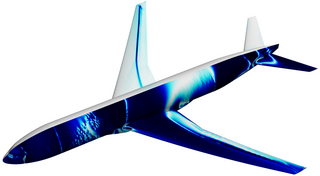

In fluid dynamics, turbulence or turbulent flow is fluid motion characterized by chaotic changes in pressure and flow velocity. It is in contrast to a laminar flow, which occurs when a fluid flows in parallel layers, with no disruption between those layers.

In continuum mechanics, the infinitesimal strain theory is a mathematical approach to the description of the deformation of a solid body in which the displacements of the material particles are assumed to be much smaller than any relevant dimension of the body; so that its geometry and the constitutive properties of the material at each point of space can be assumed to be unchanged by the deformation.

In physics and fluid mechanics, a boundary layer is the thin layer of fluid in the immediate vicinity of a bounding surface formed by the fluid flowing along the surface. The fluid's interaction with the wall induces a no-slip boundary condition. The flow velocity then monotonically increases above the surface until it returns to the bulk flow velocity. The thin layer consisting of fluid whose velocity has not yet returned to the bulk flow velocity is called the velocity boundary layer.

A Newtonian fluid is a fluid in which the viscous stresses arising from its flow are at every point linearly correlated to the local strain rate — the rate of change of its deformation over time. Stresses are proportional to the rate of change of the fluid's velocity vector.

In Hamiltonian mechanics, a canonical transformation is a change of canonical coordinates (q, p) → that preserves the form of Hamilton's equations. This is sometimes known as form invariance. Although Hamilton's equations are preserved, it need not preserve the explicit form of the Hamiltonian itself. Canonical transformations are useful in their own right, and also form the basis for the Hamilton–Jacobi equations and Liouville's theorem.

Large eddy simulation (LES) is a mathematical model for turbulence used in computational fluid dynamics. It was initially proposed in 1963 by Joseph Smagorinsky to simulate atmospheric air currents, and first explored by Deardorff (1970). LES is currently applied in a wide variety of engineering applications, including combustion, acoustics, and simulations of the atmospheric boundary layer.

In thermodynamics, the heat transfer coefficient or film coefficient, or film effectiveness, is the proportionality constant between the heat flux and the thermodynamic driving force for the flow of heat. It is used in calculating the heat transfer, typically by convection or phase transition between a fluid and a solid. The heat transfer coefficient has SI units in watts per square meter per kelvin (W/m²K).

In fluid dynamics, the Reynolds stress is the component of the total stress tensor in a fluid obtained from the averaging operation over the Navier–Stokes equations to account for turbulent fluctuations in fluid momentum.

In fluid dynamics, the Schmidt number of a fluid is a dimensionless number defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity and mass diffusivity, and it is used to characterize fluid flows in which there are simultaneous momentum and mass diffusion convection processes. It was named after German engineer Ernst Heinrich Wilhelm Schmidt (1892–1975).

In fluid dynamics, turbulence modeling is the construction and use of a mathematical model to predict the effects of turbulence. Turbulent flows are commonplace in most real-life scenarios. In spite of decades of research, there is no analytical theory to predict the evolution of these turbulent flows. The equations governing turbulent flows can only be solved directly for simple cases of flow. For most real-life turbulent flows, CFD simulations use turbulent models to predict the evolution of turbulence. These turbulence models are simplified constitutive equations that predict the statistical evolution of turbulent flows.

In fluid dynamics, turbulence kinetic energy (TKE) is the mean kinetic energy per unit mass associated with eddies in turbulent flow. Physically, the turbulence kinetic energy is characterized by measured root-mean-square (RMS) velocity fluctuations. In the Reynolds-averaged Navier Stokes equations, the turbulence kinetic energy can be calculated based on the closure method, i.e. a turbulence model.

In radiometry, radiosity is the radiant flux leaving a surface per unit area, and spectral radiosity is the radiosity of a surface per unit frequency or wavelength, depending on whether the spectrum is taken as a function of frequency or of wavelength. The SI unit of radiosity is the watt per square metre, while that of spectral radiosity in frequency is the watt per square metre per hertz (W·m−2·Hz−1) and that of spectral radiosity in wavelength is the watt per square metre per metre (W·m−3)—commonly the watt per square metre per nanometre. The CGS unit erg per square centimeter per second is often used in astronomy. Radiosity is often called intensity in branches of physics other than radiometry, but in radiometry this usage leads to confusion with radiant intensity.

Shear velocity, also called friction velocity, is a form by which a shear stress may be re-written in units of velocity. It is useful as a method in fluid mechanics to compare true velocities, such as the velocity of a flow in a stream, to a velocity that relates shear between layers of flow.

In fluid dynamics, the Reynolds number is a dimensionless quantity that helps predict fluid flow patterns in different situations by measuring the ratio between inertial and viscous forces. At low Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be dominated by laminar (sheet-like) flow, while at high Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be turbulent. The turbulence results from differences in the fluid's speed and direction, which may sometimes intersect or even move counter to the overall direction of the flow. These eddy currents begin to churn the flow, using up energy in the process, which for liquids increases the chances of cavitation.

In engineering, physics, and chemistry, the study of transport phenomena concerns the exchange of mass, energy, charge, momentum and angular momentum between observed and studied systems. While it draws from fields as diverse as continuum mechanics and thermodynamics, it places a heavy emphasis on the commonalities between the topics covered. Mass, momentum, and heat transport all share a very similar mathematical framework, and the parallels between them are exploited in the study of transport phenomena to draw deep mathematical connections that often provide very useful tools in the analysis of one field that are directly derived from the others.

In fluid dynamics, the entrance length is the distance a flow travels after entering a pipe before the flow becomes fully developed. Entrance length refers to the length of the entry region, the area following the pipe entrance where effects originating from the interior wall of the pipe propagate into the flow as an expanding boundary layer. When the boundary layer expands to fill the entire pipe, the developing flow becomes a fully developed flow, where flow characteristics no longer change with increased distance along the pipe. Many different entrance lengths exist to describe a variety of flow conditions. Hydrodynamic entrance length describes the formation of a velocity profile caused by viscous forces propagating from the pipe wall. Thermal entrance length describes the formation of a temperature profile. Awareness of entrance length may be necessary for the effective placement of instrumentation, such as fluid flow meters.