Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously through the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity. When the cause of the convection is unspecified, convection due to the effects of thermal expansion and buoyancy can be assumed. Convection may also take place in soft solids or mixtures where particles can flow.

The Prandtl number (Pr) or Prandtl group is a dimensionless number, named after the German physicist Ludwig Prandtl, defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity. The Prandtl number is given as:

In fluid mechanics, the Grashof number is a dimensionless number which approximates the ratio of the buoyancy to viscous forces acting on a fluid. It frequently arises in the study of situations involving natural convection and is analogous to the Reynolds number.

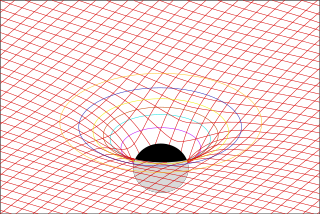

The stress–energy tensor, sometimes called the stress–energy–momentum tensor or the energy–momentum tensor, is a tensor physical quantity that describes the density and flux of energy and momentum in spacetime, generalizing the stress tensor of Newtonian physics. It is an attribute of matter, radiation, and non-gravitational force fields. This density and flux of energy and momentum are the sources of the gravitational field in the Einstein field equations of general relativity, just as mass density is the source of such a field in Newtonian gravity.

In physics and fluid mechanics, a boundary layer is the thin layer of fluid in the immediate vicinity of a bounding surface formed by the fluid flowing along the surface. The fluid's interaction with the wall induces a no-slip boundary condition. The flow velocity then monotonically increases above the surface until it returns to the bulk flow velocity. The thin layer consisting of fluid whose velocity has not yet returned to the bulk flow velocity is called the velocity boundary layer.

The Hagen number (Hg) is a dimensionless number used in forced flow calculations. It is the forced flow equivalent of the Grashof number and was named after the German hydraulic engineer G. H. L. Hagen.

There are two different Bejan numbers (Be) used in the scientific domains of thermodynamics and fluid mechanics. Bejan numbers are named after Adrian Bejan.

The Rayleigh–Taylor instability, or RT instability, is an instability of an interface between two fluids of different densities which occurs when the lighter fluid is pushing the heavier fluid. Examples include the behavior of water suspended above oil in the gravity of Earth, mushroom clouds like those from volcanic eruptions and atmospheric nuclear explosions, supernova explosions in which expanding core gas is accelerated into denser shell gas, instabilities in plasma fusion reactors and inertial confinement fusion.

In theoretical physics, the superconformal algebra is a graded Lie algebra or superalgebra that combines the conformal algebra and supersymmetry. In two dimensions, the superconformal algebra is infinite-dimensional. In higher dimensions, superconformal algebras are finite-dimensional and generate the superconformal group.

In physics and fluid mechanics, a Blasius boundary layer describes the steady two-dimensional laminar boundary layer that forms on a semi-infinite plate which is held parallel to a constant unidirectional flow. Falkner and Skan later generalized Blasius' solution to wedge flow, i.e. flows in which the plate is not parallel to the flow.

In physics, Maxwell's equations in curved spacetime govern the dynamics of the electromagnetic field in curved spacetime or where one uses an arbitrary coordinate system. These equations can be viewed as a generalization of the vacuum Maxwell's equations which are normally formulated in the local coordinates of flat spacetime. But because general relativity dictates that the presence of electromagnetic fields induce curvature in spacetime, Maxwell's equations in flat spacetime should be viewed as a convenient approximation.

In many-body theory, the term Green's function is sometimes used interchangeably with correlation function, but refers specifically to correlators of field operators or creation and annihilation operators.

An Ubbelohde type viscometer or suspended-level viscometer is a measuring instrument which uses a capillary based method of measuring viscosity. It is recommended for higher viscosity cellulosic polymer solutions. The advantage of this instrument is that the values obtained are independent of the total volume. The device was developed by the German chemist Leo Ubbelohde (1877-1964).

Acoustic streaming is a steady flow in a fluid driven by the absorption of high amplitude acoustic oscillations. This phenomenon can be observed near sound emitters, or in the standing waves within a Kundt's tube. Acoustic streaming was explained first by Lord Rayleigh in 1884. It is the less-known opposite of sound generation by a flow.

In non ideal fluid dynamics, the Hagen–Poiseuille equation, also known as the Hagen–Poiseuille law, Poiseuille law or Poiseuille equation, is a physical law that gives the pressure drop in an incompressible and Newtonian fluid in laminar flow flowing through a long cylindrical pipe of constant cross section. It can be successfully applied to air flow in lung alveoli, or the flow through a drinking straw or through a hypodermic needle. It was experimentally derived independently by Jean Léonard Marie Poiseuille in 1838 and Gotthilf Heinrich Ludwig Hagen, and published by Hagen in 1839 and then by Poiseuille in 1840–41 and 1846. The theoretical justification of the Poiseuille law was given by George Stokes in 1845.

Double diffusive convection is a fluid dynamics phenomenon that describes a form of convection driven by two different density gradients, which have different rates of diffusion.

The table of chords, created by the Greek astronomer, geometer, and geographer Ptolemy in Egypt during the 2nd century AD, is a trigonometric table in Book I, chapter 11 of Ptolemy's Almagest, a treatise on mathematical astronomy. It is essentially equivalent to a table of values of the sine function. It was the earliest trigonometric table extensive enough for many practical purposes, including those of astronomy. Since the 8th and 9th centuries, the sine and other trigonometric functions have been used in Islamic mathematics and astronomy, reforming the production of sine tables. Khwarizmi and Habash al-Hasib later produced a set of trigonometric tables.

In fluid dynamics, the Falkner–Skan boundary layer describes the steady two-dimensional laminar boundary layer that forms on a wedge, i.e. flows in which the plate is not parallel to the flow. It is also representative of flow on a flat plate with an imposed pressure gradient along the plate length, a situation often encountered in wind tunnel flow. It is a generalization of the flat plate Blasius boundary layer in which the pressure gradient along the plate is zero.

In fluid dynamics, a stagnation point flow refers to a fluid flow in the neighbourhood of a stagnation point or a stagnation line with which the stagnation point/line refers to a point/line where the velocity is zero in the inviscid approximation. The flow specifically considers a class of stagnation points known as saddle points wherein incoming streamlines gets deflected and directed outwards in a different direction; the streamline deflections are guided by separatrices. The flow in the neighborhood of the stagnation point or line can generally be described using potential flow theory, although viscous effects cannot be neglected if the stagnation point lies on a solid surface.

The shear viscosity of a fluid is a material property that describes the friction between internal neighboring fluid surfaces flowing with different fluid velocities. This friction is the effect of (linear) momentum exchange caused by molecules with sufficient energy to move between these fluid sheets due to fluctuations in their motion. The viscosity is not a material constant, but a material property that depends on temperature, pressure, fluid mixture composition, local velocity variations. This functional relationship is described by a mathematical viscosity model called a constitutive equation which is usually far more complex than the defining equation of shear viscosity. One such complicating feature is the relation between the viscosity model for a pure fluid and the model for a fluid mixture which is called mixing rules. When scientists and engineers use new arguments or theories to develop a new viscosity model, instead of improving the reigning model, it may lead to the first model in a new class of models. This article will display one or two representative models for different classes of viscosity models, and these classes are: