Related Research Articles

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is an independent agency of the United States federal government, created in the aftermath of the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The primary purpose of the SEC is to enforce the law against market manipulation.

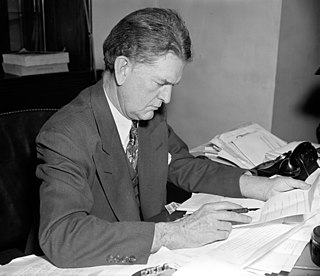

Brazilla Carroll Reece was an American Republican Party politician from Tennessee. He represented eastern Tennessee in the United States House of Representatives for all but six years from 1921 to 1961 and served as the Chair of the Republican National Committee from 1946 to 1948. A conservative, he led the party's Old Right wing alongside Robert A. Taft in crusading against interventionism, communism, and the liberal policies pursued by the Roosevelt and Truman administrations.

Charles Christopher Cox is an American attorney and politician who served as chair of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, a 17-year Republican member of the United States House of Representatives, and member of the White House staff in the Reagan Administration. Prior to his Washington service he was a practicing attorney, teacher, and entrepreneur. Following his retirement from government in 2009, he returned to law practice and currently serves as a director, trustee, and advisor to several for-profit and nonprofit organizations.

The sponsorship scandal, AdScam or Sponsorgate, was a scandal in Canada that came as a result of a federal government "sponsorship program" in the province of Quebec involving the Liberal Party of Canada, which was in power from 1993 to 2006.

In the United States Senate, the La Follette Civil Liberties Committee, or more formally, Committee on Education and Labor, Subcommittee Investigating Violations of Free Speech and the Rights of Labor (1936–1941), began as an inquiry into a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) investigation of methods used by employers in certain industries to avoid collective bargaining with unions.

The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) is a nonprofit corporation created by the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 to oversee the audits of US-listed public companies. The PCAOB also oversees the audits of broker-dealers, including compliance reports filed pursuant to federal securities laws, to promote investor protection. All PCAOB rules and standards must be approved by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Congressional oversight is oversight by the United States Congress over the executive branch, including the numerous U.S. federal agencies. Congressional oversight includes the review, monitoring, and supervision of federal agencies, programs, activities, and policy implementation. Congress exercises this power largely through its congressional committee system. Oversight also occurs in a wide variety of congressional activities and contexts. These include authorization, appropriations, investigative, and legislative hearings by standing committees; which is specialized investigations by select committees; and reviews and studies by congressional support agencies and staff.

A 501(c)(3) organization is a United States corporation, trust, unincorporated association or other type of organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501(c)(3) of Title 26 of the United States Code. It is one of the 29 types of 501(c) nonprofit organizations in the US.

A supporting organization, in the United States, is a public charity that operates under the U.S. Internal Revenue Code in 26 USCA 509(a)(3). A supporting organization either makes grants to, or performs the operations of, a public charity similar to a private foundation.

Edward Eugene "Eugene" or "Goober" Cox served as a U.S. representative from Georgia for nearly 28 years. A conservative Democrat who supported racial segregation and opposed President Franklin Roosevelt's "New Deal," Cox became the most senior Democrat on the House Committee on Rules.

A private foundation is a tax-exempt organization that does not rely on broad public support and generally claims to serve humanitarian purposes.

A foundation in the United States is a type of charitable organization. However, the Internal Revenue Code distinguishes between private foundations and public charities. Private foundations have more restrictions and fewer tax benefits than public charities like community foundations.

Until 1969, the term private foundation was not defined in the United States Internal Revenue Code. Since then, every U.S. charity that qualifies under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Service Code as tax-exempt is a "private foundation" unless it demonstrates to the IRS that it falls into another category such as public charity. Unlike nonprofit corporations classified as a public charity, private foundations in the United States are subject to a 1.39% excise tax or endowment tax on any net investment income.

Norman Paul Dodd was an American banker and bank manager, who worked as a financial advisor and served as chief investigator in 1953 for the Special Committee on Tax Exempt Foundations, which was chaired by U.S. Congressman B. Carroll Reece. Dodd was known primarily for his controversial investigation into tax-exempt foundations.

The Commission on Private Philanthropy and Public Needs, better known as the Filer Commission, was formed in 1973 to study philanthropy, the role of the private sector in American society, and then to recommend measures to increase voluntary giving. Organized as a privately supported citizen's board, the Commission came into being through the efforts of John D. Rockefeller III, Wilbur D. Mills, George P. Shultz, and William E. Simon. The selection of participants on the Commission reflected a desire for diversity of experience and opinions and included heads of religious and labor groups, former cabinet secretaries, corporate and Foreign Securities Corporation and President of Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Edwin D. Etherington, Former President of Wesleyan University and Trustee of Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

- Bayard Ewing, Tillinghast, Collins and Graham and Vice Chairman of United Way of America.

- Frances Tarlton Farenthold, Past Chairperson of National Women's Political Caucus.

- Max M. Fisher, Chairman of United Brands Company and Honorary Chairman of United Foundations.

- Reverend Raymond J. Gallagher, Bishop of Lafayette-in-Indiana.

- Earl G. Graves, Publisher of Black Enterprise and Commissioner of Boy Scouts of America.

- Paul R. Haas, President and Chairman of Corpus Christi Oil and Gas Company and Trustee of Paul and Mary Haas Foundation.

- Walter A. Haas Jr., Chairman of Levi Strauss and Company and Trustee of the Ford Foundation.

- Philip M. Klutznick, Klutznick Investments and Chairman of Research and Policy Committee and Trustee of Committee for Economic Development.

- Ralph Lazarus, Chairman of Federated Department Stores, Inc. and Former National Chairman of United Way of America.

- Herbert E. Longenecker, President Emeritus of Tulane University and Director of United Student Aid Funds.

- Elizabeth J. McCormack, Special Assistant to the President of Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Inc.

- Walter J. McNerney, President of Blue Cross Association.

- William H. Morton, Trustee of Dartmouth College.

- John M. Musser, President and Director of General Service Foundation.

- Jon O. Newman, Judge, U.S. District Court and Chairman of Hartford Institute of Criminal and Social Justice.

- Graciela Olivarez, State Planning Officer and Director of Council on Foundations, Inc.

- Alan Pifer, President of Carnegie Corporation of New York.

- George Romney, Chairman of the National Center for Voluntary Action.

- William Matson Roth, Regent of University of California and Chairman of San Francisco Museum of Art.

- Althea T. L. Simmons, Director for Education Programs of the NAACP Special Contribution Fund.

- Reverend Leon H. Sullivan, Pastor of Zion Baptist Church, Philadelphia.

- David B. Truman, President of Mount Holyoke College.

The United States Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management was a select committee created by the United States Senate on January 30, 1957 and dissolved on March 31, 1960. The select committee was directed to study the extent of criminal or other improper practices in the field of labor-management relations or in groups of employees or employers, and to recommend changes in the laws of the United States that would provide protection against such practices or activities. It conducted 253 active investigations, served 8,000 subpoenas for witnesses and documents, held 270 days of hearings, took testimony from 1,526 witnesses, and compiled almost 150,000 pages of testimony. At the peak of its activity in 1958, 104 persons worked for the committee. The select committee's work led directly to the enactment of the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act on September 14, 1959.

The Johnson Amendment is a provision in the U.S. tax code, since 1954, that prohibits all 501(c)(3) non-profit organizations from endorsing or opposing political candidates. Section 501(c)(3) organizations are the most common type of nonprofit organization in the United States, ranging from charitable foundations to universities and churches. The amendment is named for then-Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas, who introduced it in a preliminary draft of the law in July 1954.

In 2013, the United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS), under the Obama administration, revealed that it had selected political groups applying for tax-exempt status for intensive scrutiny based on their names or political themes. This led to wide condemnation of the agency and triggered several investigations, including a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) criminal probe ordered by United States Attorney General Eric Holder. Conservatives claimed that they were specifically targeted by the IRS, but an exhaustive report released by the Treasury Department's Inspector General in 2017 found that from 2004 to 2013, the IRS used both conservative and liberal keywords to choose targets for further scrutiny.

The impeachment process against Richard Nixon was initiated by the United States House of Representatives on October 30, 1973, during the course of the Watergate scandal, when multiple resolutions calling for the impeachment of President Richard Nixon were introduced immediately following the series of high-level resignations and firings widely called the "Saturday Night Massacre". The House Committee on the Judiciary soon began an official investigation of the president's role in Watergate, and, in May 1974, commenced formal hearings on whether sufficient grounds existed to impeach Nixon of high crimes and misdemeanors under Article II, Section 4, of the United States Constitution. This investigation was undertaken one year after the United States Senate established the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities to investigate the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex during the 1972 presidential election, and the Republican Nixon administration's attempted cover-up of its involvement; during those hearings the scope of the scandal became apparent and the existence of the Nixon White House tapes was revealed.

Mississippi Today is the state's flagship nonprofit newsroom based in Ridgeland, Mississippi, and winner of the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting. It was founded in 2016 by former Netscape president and CEO Jim Barksdale and his wife, Donna, alongside former NBC chairman Andrew Lack. It is focused on watchdog journalism related to Mississippi's state and local government, health, economy, environment, public schools and universities, and the justice system.

References

- ↑ Walter Stubbs (1985), Congressional Committees, 1789-1982: A Checklist, Greenwood Press, p. 133

- 1 2 3 http://www.2facts.com.wylproxy.minlib.net/Archive/temp/76987temp1954020050.asp?DBType=News Archived 2022-10-31 at the Wayback Machine World News Digest: Foundations Probe: Reece Unit vs. Foundations; Other Developments (subscription required)

- 1 2 Harry D. Gideonse, "A Congressional Committee's Investigation of the Foundations" The Journal of Higher Education 25#9 (Dec., 1954), pp. 457-463.

- 1 2 3 J. Steven Ott, ed. (2000). The Nonprofit Sector: An Overview. University of Utah: Westview Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 0-8133-6785-9.

- ↑ U.S. House of Representatives (1953). Hearings Before the Select Committee on Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations. Hearings, 82nd Congress. Vol. 97. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ "Dodd Report to the Reece Committee on Foundations (1954)". p. 5.

- 1 2 "Dodd Report to the Reece Committee on Foundations (1954)". p. 6.

- ↑ Dwight Macdonald, "Profiles: Ford Foundation I", New Yorker, 26 November 1955, p94