Related Research Articles

Computer science is the study of computation, information, and automation. Computer science spans theoretical disciplines to applied disciplines.

The history of computing hardware covers the developments from early simple devices to aid calculation to modern day computers.

A punched card is a piece of card stock that stores digital data using punched holes. Punched cards were once common in data processing and the control of automated machines.

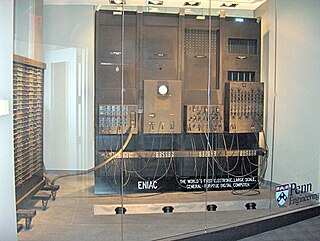

ENIAC was the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer, completed in 1945. Other computers had some of these features, but ENIAC was the first to have them all. It was Turing-complete and able to solve "a large class of numerical problems" through reprogramming.

The Harvard Mark I, or IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator (ASCC), was one of the earliest general-purpose electromechanical computers used in the war effort during the last part of World War II.

The IBM 701 Electronic Data Processing Machine, known as the Defense Calculator while in development, was IBM’s first commercial scientific computer and its first series production mainframe computer, which was announced to the public on May 21, 1952. It was designed and developed by Jerrier Haddad and Nathaniel Rochester and was based on the IAS machine at Princeton.

IBM Research is the research and development division for IBM, an American multinational information technology company headquartered in Armonk, New York, with operations in over 170 countries. IBM Research is the largest industrial research organization in the world and has twelve labs on six continents.

The IBM Card-Programmed Electronic Calculator or CPC was announced by IBM in May 1949. Later that year an improved machine, the CPC-II, was also announced.

Herman Heine Goldstine was a mathematician and computer scientist, who worked as the director of the IAS machine at the Institute for Advanced Study and helped to develop ENIAC, the first of the modern electronic digital computers. He subsequently worked for many years at IBM as an IBM Fellow, the company's most prestigious technical position.

Leslie John Comrie FRS was an astronomer and a pioneer in mechanical computation.

Starting at the end of the nineteenth century, well before the advent of electronic computers, data processing was performed using electromechanical machines collectively referred to as unit record equipment, electric accounting machines (EAM) or tabulating machines. Unit record machines came to be as ubiquitous in industry and government in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century as computers became in the last third. They allowed large volume, sophisticated data-processing tasks to be accomplished before electronic computers were invented and while they were still in their infancy. This data processing was accomplished by processing punched cards through various unit record machines in a carefully choreographed progression. This progression, or flow, from machine to machine was often planned and documented with detailed flowcharts that used standardized symbols for documents and the various machine functions. All but the earliest machines had high-speed mechanical feeders to process cards at rates from around 100 to 2,000 per minute, sensing punched holes with mechanical, electrical, or, later, optical sensors. The operation of many machines was directed by the use of a removable plugboard, control panel, or connection box. Initially all machines were manual or electromechanical. The first use of an electronic component was in 1937 when a photocell was used in a Social Security bill-feed machine. Electronic components were used on other machines beginning in the late 1940s.

The tabulating machine was an electromechanical machine designed to assist in summarizing information stored on punched cards. Invented by Herman Hollerith, the machine was developed to help process data for the 1890 U.S. Census. Later models were widely used for business applications such as accounting and inventory control. It spawned a class of machines, known as unit record equipment, and the data processing industry.

The Thomas J. Watson Research Center is the headquarters for IBM Research. Its main laboratory is in Yorktown Heights, New York, 38 miles (61 km) north of New York City. It also operates facilities in Cambridge, Massachusetts and Albany, New York.

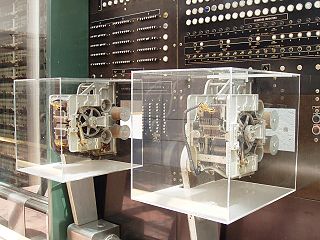

The IBM Selective Sequence Electronic Calculator (SSEC) was an electromechanical computer built by IBM. Its design was started in late 1944 and it operated from January 1948 to August 1952. It had many of the features of a stored-program computer, and was the first operational machine able to treat its instructions as data, but it was not fully electronic. Although the SSEC proved useful for several high-profile applications, it soon became obsolete. As the last large electromechanical computer ever built, its greatest success was the publicity it provided for IBM.

Herbert Reuben John Grosch was an early computer scientist, perhaps best known for Grosch's law, which he formulated in 1950. Grosch's Law is an aphorism that states "economy is as the square root of the speed."

Gerald Maurice Clemence was an American astronomer. Inspired by the life and work of Simon Newcomb, his career paralleled the huge advances in astronomy brought about by the advent of the electronic computer. Clemence did much to revive the prestige of the U.S. Nautical Almanac Office.

Cuthbert Corwin Hurd was an American computer scientist and entrepreneur, who was instrumental in helping the International Business Machines Corporation develop its first general-purpose computers.

The IBM Naval Ordnance Research Calculator (NORC) was a one-of-a-kind first-generation computer built by IBM for the United States Navy's Bureau of Ordnance. It went into service in December 1954 and was likely the most powerful computer at the time. The Naval Ordnance Research Calculator (NORC), was built at the Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory under the direction of Wallace Eckert.

The IBM 601 Multiplying Punch was a unit record machine that could read two numbers from a punched card and punch their product in a blank field on the same card. The factors could be up to eight decimal digits long. The 601 was introduced in 1931 and was the first IBM machine that could do multiplication.

Eleanor Krawitz Kolchin was an American mathematician, computer programmer, author, and teacher. She worked at Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory at Columbia University to calculate the orbit of planets, phases of the moon, and trajectories of asteroids using IBM tabulating machines. Her calculations were used in the Apollo program.

References

- ↑ Hockey, Thomas (2009). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0 . Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- 1 2 John A. N. Lee (1995). "Wallace J. Eckert". International biographical dictionary of computer pioneers. Taylor & Francis for IEEE Computer Society Press. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-1-884964-47-3.

- ↑ Frank da Cruz. "Professor Wallace J. Eckert". A Chronology of Computing at Columbia University. Columbia University . Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ Freeman, William M. (August 25, 1971). "Dr. Wallace Eckert Dies at 69; Tracked Moon with Computer". New York Times . Retrieved February 2, 2013. Alt URL

- ↑ Eckert, Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, International Astronomical Union (IAU) Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN)

- ↑ "Endicott chronology — 1931-1939". IBM archives web site. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ Frank da Cruz. "The US Naval Observatory 1940-45". A Chronology of Computing at Columbia University web site. Columbia University . Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ "History of the Astronomical Applications Department". US Naval Observatory web site. Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ Francis H. Harlow; Nicholas Metropolis (Winter–Spring 1983). "Computing & Computers: Weapons Simulation Leads to the Computer Era" (PDF). Los Alamos Science . pp. 133–134. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ Dyson, Turing's Cathedral

- ↑ Kevin Maney (2004). The Maverick and His Machine: Thomas Watson, Sr. and the Making of IBM. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 347–355. ISBN 978-0-471-67925-7.

- ↑ W. J. Eckert (November 1948). "Electrons and Computation". The Scientific Monthly . ISBN 9783540113195.

- ↑ Frank da Cruz. "Herb Grosch September 13, 1918 – January 25, 2010". A Chronology of Computing at Columbia University web site. Columbia University . Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ Frank da Cruz. "L.H. Thomas and Wallace Eckert in Watson Lab, Columbia University". A Chronology of Computing at Columbia University web site. Columbia University . Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ Nancy Stern (January 20, 1981). "An Interview with Cuthbert C. Hurd". Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Watson Research Center,Yorktown Heights, NY". IBM Research web site. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ "James Craig Watson Medal". United States National Academy of Sciences . Retrieved June 4, 2010.