Description

Wani first occurs in two ancient Japanese "mytho-histories", the ca. 680 CE Kojiki and ca. 720 CE Nihongi . They write wani with the Man'yōgana phonetic transcription 和邇 and the kanji 鰐.

The Kojiki uses wani 和邇 several times as a proper name (e.g., the Confucianist scholar Wani ) and as a sea-monster in two contexts. First, in the "White Hare of Inaba" fable, the gods try and fail to help a shiro 白 (lit. "white") "naked; hairless" hare that they found crying on a beach.

But the Deity Great-Name-Possessor, who came last of all, saw the hare, and said: "Why liest thou weeping?" The hare replied, saying: "I was in the Island of Oki, and wished to cross over to this land, but had no means of crossing over. For this reason I deceived the crocodiles of the sea, saying: 'Let you and me compete, and compute the numbers of our [respective] tribes. So do you go and fetch every member of your tribe, and make them all lie in a row across from this island to Cape Keta. Then I will tread on them, and count them as I run across. Hereby shall we know whether it or my tribe is the larger.' Upon my speaking thus, they were deceived and lay down in a row, and I trod on them and counted them as I came across, and was just about to get on land, when I said: 'You have been deceived by me.' As soon as I had finished speaking, the crocodile who lay the last of all seized me and stripped off all my clothing. As I was weeping and lamenting for this reason, the eighty Deities who went by before [thee] commanded and exhorted me, saying: 'Bathe in the salt water, and lie down exposed to the wind.' So, on my doing as they had instructed me, my whole body was hurt." Thereupon the Deity Great-Name-Possessor instructed the hare, saying: "Go quickly now to the river-mouth, wash thy body with the fresh water, then take the pollen of the sedges [growing] at the river-mouth, spread it about, and roll about upon it, whereupon thy body will certainly be restored to its original state." So [the hare] did as it was instructed, and its body became as it had been originally. This was the White Hare of Inaba. It is now called the Hare Deity.

Second, wani is a fundamental theme in the myth of the demigod brothers Hoori and Hoderi. The sea god Watatsumi or Ryūjin "summoned together all the crocodiles" and chose one to escort his pregnant daughter Toyotama-hime and her husband Hoori from the Ryūgū-jō palace back to land. Soon after their arrival, the beautiful Toyatama-hime made a bizarre request concerning her shapeshifting into a wani.

Then, when she was about to be delivered, she spoke to her husband [saying]: "Whenever a foreigner is about to be delivered, she takes the shape of her native land to be delivered. So I now will take my native shape to be delivered. Pray look not upon me!" Hereupon [His Augustness Fire-Subside], thinking these words strange, stealthily peeped at the very moment of delivery, when she turned into a crocodile eight fathoms [long], and crawled and writhed about; and he forthwith, terrified at the sight, fled away. Then Her Augustness Luxuriant-Jewel-Princess knew that he had peeped; and she felt ashamed, and, straightway leaving the august child which she had borne, she said: 'I had wished always to come and go across the sea-path. But thy having peeped at my [real] shape [makes me] very shame-faced," – and she forthwith closed the sea-boundary, and went down again.

Basil Hall Chamberlain compared Ernest Mason Satow's translation of wani as "sea shark". [5] "The hare replied: 'I was in the Island of the Offing and wished to cross over to this land, but having no means of doing so, cheated the sea sharks (wani)'." Chamberlain justified translating "crocodile" in a footnote.

There is perhaps some want of clearness in the old historical books in the details concerning the creature in question, and its fin is mentioned in the "Chronicles." But the accounts point rather to an amphibious creature, conceived of as being somewhat similar to the serpent, than to a fish, and the Chinese descriptions quoted by the Japanese commentators unmistakably refer to the crocodile. The translator therefore sees no sufficient reason for abandoning the usually accepted interpretation of wani (鰐) as "crocodile." It should be noticed that the wani is never introduced into any but patently fabulous stories, and that the example of other nations, and indeed of Japan itself, shows that myth-makers have no objection to embellish their tales by the mention of wonders supposed to exist in foreign lands.

The Nihongi likewise uses wani several times as a proper name (e.g., a mountain pass called "Wani acclivity"), and twice in the word kuma-wani 熊鰐 "bear (i.e., giant or strong) shark/crocodile". First, the mythical sea god Kotoshiro-nushi-no-kami (see Ebisu) is described as a ya-hiro no kuma-wani 八尋熊鰐 "8-fathom bear-wani". De Visser says "The epithet "bear" means 'strong as a bear'".

Another version is that Koto-shiro-nushi no Kami, having become transformed into an eight-fathom bear-sea-monster, had intercourse with Mizo-kuhi hime of the island of Mishima (some call her Tama-kushi-hime), and had by her a child named Hime-tatara I-suzu-hime no Mikoto, who became the Empress of Emperor Kami-Yamato Ihare-biko Hohodemi.

Second, the Nihongi chapters on legendary Emperor Chūai and his Empress Jingū combine two myths of Japanese tide jewels and Indian nyoi-ju 如意珠 "cintamani; wish-fulfilling jewels". In 193 CE, the Empress supposedly "found in the sea a Nyoi pearl", and in 199 CE, the imperial ships encountered a kuma-wani with a giant tamagushi .

The Emperor proceeded to Tsukushi. At this time Kuma-wani, the ancestor of the Agata-nushi of Oka, hearing of the Emperor's arrival, pulled up beforehand a 500-branched Sakaki tree, which he set up on the bows of a nine-fathom ship. On the upper branches he hung a white-copper mirror, on the middle branches he hung a ten-span sword, and on the lower branches he hung Yasaka jewels. With these he went out to meet him at the Bay of Saha in Suwo, and presented to him a fish-salt-place. In doing so, he addressed the Emperor, saying: "Let the Great Ferry from Anato to Mukatsuno be its Eastern Gate and the Great Ferry of Nagoya be its Western Gate. Let the Islands of Motori and Abe and none else be the august baskets: let the Island of Shiba be divided and made the august pans: let the Sea of Sakami be the salt-place." He then acted as the Emperor's pilot. Going round Cape Yamaga, he entered the Bay of Oka. But in entering the harbour, the ship was unable to go forward. So he inquired of Kuma-wani, saying: "We have heard that thou, Kuma-wani, hast come to us with an honest heart. Why does the ship not proceed?" Kuma-wani addressed the Emperor, saying: "It is not the fault of thy servant that the august ship is unable to advance. At the entrance to this bay there are two Deities, one male and the other female. The male Deity is called Oho-kura-nushi, the female Deity is called Tsubura-hime. It must be owing to the wish of these Deities." The Emperor accordingly prayed to them, and caused them to be sacrificed to, appointing his steersman Iga-hiko, a man of Uda in the province of Yamato, as priest. So the ship was enabled to proceed. The Empress entered in a different ship by the Sea of Kuki. As the tide was out, she was unable to go on. Then Kuma-wani went back and met the Empress by way of Kuki. Thereupon he saw that the august ship made no progress, and he was afraid. He hastily made a fish-pond and a bird-pond, into which he collected all the fishes and birds. When the Empress saw these fishes and birds sporting, her anger was gradually appeased, and with the flowing tide she straightway anchored in the harbour of Oka.

William George Aston justified not translating wani as "crocodile". He refers to the Ryūjin 龍神 "dragon god", his daughter Toyotama-hime 豊玉姫 "luminous jewel princess" (who married the Japanese imperial ancestor Hoori or Hohodemi), Dragon King myths, and the scholar Wani who served Emperor Ōjin.

Sea-monster is in Japanese wani. It is written with a Chinese character which means, properly, crocodile, but that meaning is inadmissible in these old legends, as the Japanese who originated them can have known nothing of this animal. The wani, too, inhabits the sea and not rivers, and is plainly a mythical creature. Satow and Anderson have noted that the wani is usually represented in art as a dragon, and Toyo-tama-hime … who in one version of the legend changes into a wani, as her true form at the moment of child-birth, according to another changes into a dragon. Now Toyo-tama-hime was the daughter of the God of the Sea. This suggests that the latter is one of the Dragon-Kings familiar to Chinese … and Corean [ sic ] fable who inhabit splendid palaces at the bottom of the sea. … It is possible that wani is for the Corean wang-i, i.e. "the King," i being the Corean definite particle, as in zeni, fumi, yagi, and other Chinese words which reached Japan via Corea? We have the same change of ng into n in the name of the Corean who taught Chinese to the Japanese Prince Imperial in Ojin Tenno's reign. It is Wang-in in Corean, but was pronounced Wani by the Japanese. Wani occurs several times as a proper name in the "Nihongi". Bear (in Japanese kuma) is no doubt an epithet indicating size, as in kuma-bachi, bear-bee or bear-wasp, i.e. a hornet; kuma-gera, a large kind of wood-pecker, etc.

Aston later wrote that.

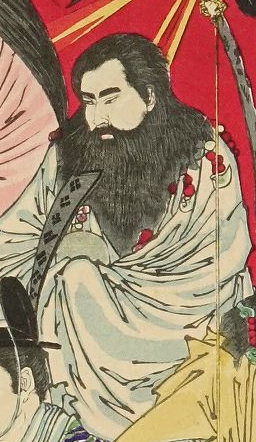

There can be little doubt that the wani is really the Chinese dragon. It is frequently so represented in Japanese pictures. I have before me a print which shows Toyotama-hiko and his daughter with dragon's heads appearing over their human ones. This shows that he was conceived of not only as a Lord of Dragons, but as a dragon himself. His daughter, who in one version of the story changes at the moment of child-bearing into a wani as her true form, in another is converted into a dragon. In Japanese myth the serpent or dragon is almost always associated with water in some of its forms.

Marinus Willem de Visser discussed the wani in detail. He compared versions of the myth about Hoori or Hohodemi seeing his sea-princess wife Toyotama-hime turning into a wani or a "dragon" during childbirth, and strongly disagrees with Aston's hypotheses about Japanese wani deriving from Korean wang-i "the king" and the wani legend having features of Chinese and Indian Dragon Kings.

Although the Indian notions about the Naga-kings related above [] are easily to be recognized in the Japanese legend, yet I think we must not go as far as to consider the whole story western, nor have we the right to suspect the old word wani because a part of the legend is of foreign origin. Why should the ancient Japanese or Koreans have called these sea-monsters "kings", omitting the word "dragon", which is the most important part of the combined term "dragon-king"? And if the full term were used in Korea, certainly the Japanese would not have taken up only its last part. In my opinion the wani is an old Japanese dragon- or serpent-shaped sea-god, and the legend is an ancient Japanese tale, dressed in an Indian garb by later generations. The oldest version probably related how Hohodemi went to the sea-god, married his daughter and obtained from him the two jewels of ebb and flood [i.e., tide jewels], or some other means to punish his brother by nearly drowning him; afterwards, when having returned to the earth, he built the parturition-house, and breaking his promise of not looking at his wife when she was giving birth, saw that she had changed into a wani, i.e. an enormous sea-monster. As to the pearls, although mysterious jewels are very common in the Indian tales about the Naga-kings, it is possible that also Japanese sea-gods were believed to possess them, as the sea conceals so many treasures in her depths; but it may also be an Indian conception. When later generations got acquainted with the Chinese and Indian dragons, they identified their wani with the latter, and embellished their old legends with features, borrowed from the Indian Naga tales.

De Visser additionally compared the Japanese Hoori/Hohodemi legend with Indonesian myths from the Kei Islands and Minahassa Peninsula.

After having written this I got acquainted with the interesting fact, pointed out by F.W.K. Müller, [ [15] ] that a similar myth is to be found as well on the Kei islands as in the Minahassa. The resemblance of several features of this myth with the Japanese one is so striking, that we may be sure that the latter is of Indonesian origin. Probably the foreign invaders, who in prehistoric times conquered Japan, came from Indonesia and brought this myth with them. In the Kei version the man who had lost the hook, lent to him by his brother, enters the clouds in a boat and at last finds the hook in the throat of a fish. In the Minahassa legend, however, he dives into the sea and arrives at a village at the bottom of the water. There he discovers the hook in the throat of a girl, and is brought home on the back of a big fish. And like Hohodemi punished his brother by nearly drowning him by means of the jewel of flood-tide, so the hero of the Minahassa legend by his prayers caused the rain to come down in torrents upon his evil friend. In Japan Buddhist influence evidently has changed the village in the sea into the palace of a Dragon king, but in the older version the sea-god and his daughter have kept their original shapes of wani, probably a kind of crocodiles, as the Chinese character indicates. An old painting of Sensai Eitaku, reproduced by MÜLLER, shows Hohodemi returning home on the back of a crocodile. It is quite possible that the form of this Indonesian myth introduced into Japan spoke about crocodiles, and that the vague conception of these animals was retained under the old name of wani, which may be an Indonesian word.

De Visser further disputed Aston's contention that "the wani is really the Chinese dragon" and concluded that the print reproduced by Aston is actually an Indian motif

… transferred to China and from there to Korea and Japan. As the sea-god in his magnificent palace was an Indian conception, Japanese art represented him, of course, in an Indian way. This is, however, no proof that the wani originally was identical with the Naga, or with the Chinese-Indian dragon-kings.

Smith disagreed with de Visser, "The wani or crocodile thus introduced from India, via Indonesia, is really the Chinese and Japanese dragon, as Aston has claimed." [19] Visser's proposal for an Indonesian wani origin is linguistically corroborated by Benedict's [20] hypothetical Proto-Austro-tai *mbaŋiwak "shark; crocodile" root that split into Japanese wani 鰐 and uo 魚 "fish".