War

Raid on Castle San Giorgio

The war broke out in 1118, and it was the Comaschi who provided the "casus belli" to the Milanese. The general council of Como, meeting in the church of San Giacomo, unanimously decided to attack the castle of San Giorgio, located in the territory of Pieve di Agno, home of the hated Landolfo da Carcano. The next day a small army of knights, led by consuls Adamo del Pero and Gaudenzio da Fontanella, left the city at dusk, passed through Borgo Vico, crossed the Roman bridge over the Breggia near the hamlet of Tavernola and after passing through Capolago, reached Magliaso. At the first light of dawn, the Comaschi broke into the castle, breaking through the door and taking by surprise the defenders, who nevertheless opposed a fierce but vain resistance. Two nephews of Landolfo, Ottone (or Datone) and Bianco (or Lanfranco), were killed in the fighting, while Landolfo himself was captured and taken in chains to Como, where he was imprisoned. [4]

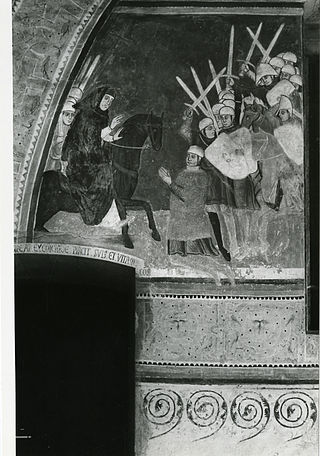

The wives of the killed men, dressed in mourning clothes and accompanied by their relatives, went to Milan and entered the cathedral of Santa Maria Maggiore carrying crosses and unfolding the bloody shirts of their husbands, kneeling crying to the archbishop of Milan and begging for justice and protection. Giordano da Clivio summoned the general council and harangued the crowd that had gathered inside and outside the cathedral, describing the insults of the Comaschi against the Diocese of Milan and the crimes committed against the noble family of Carcano, even going so far as to place a ban on the city and a ban on entering churches for all Milanese until they avenged the offenses received by the Comaschi. The general council, inflamed by the speech of the archbishop, decided to go to war. [4]

Attempted invasion of Como

After the meeting of the general council of the municipality of Milan, heralds were sent to declare war on Como and to spread the news throughout the city and in the countryside. As usual, the Carroccio was pulled by three pairs of white oxen to the cathedral square and remained there for three days during which the Martinella bell, placed on top of it, was rung, indicating the call to arms. The Milanese soldiers, divided into six companies, each for one of the six major gates of the city, gathered around their captain and went to the square, where a mass was celebrated before departure. In the countryside the war was announced by the tolling of the bells. The Comaschi prepared by reinforcing the city walls and calling to arms the people of the villages who remained loyal, among which those of Val d'Intelvi stood out. [5]

In August the Milanese army left the city from Porta Comasina and marched along the Roman road that connected Milan to Como up to a marshy plain, called Canneta or Canneda, located between the villages of Grandate and Lucino, where it camped. The Comaschi, warned by the scouts of the enemy's presence, went out with their army from Porta Pretoria, led by the consuls, and encamped between Rebbio and Grandate in order to halt the enemy advance, having the mountains on which Castel Baradello stood behind them. The next day the Milanese advanced against the Comaschi and the first armed clash of the conflict took place, the battle of Morsegna. The fighting raged until sunset, then the people of Como retreated and camped at the foot of the Baradello hill. Adamo del Pero, one of the two consuls, was killed in the fighting. At dawn the Milanese, after fortifying the positions gained the previous day, advanced as far as Rebbio, cutting off the Como army from any reinforcements coming from the city. The people of Como, to try to open up an escape route, attacked the Milanese on the flanks. In the clash a priest, son of Ardizzone da Samarate and Girolamo, the standard bearer of the Como family, fell after having fought valiantly. [6]

While part of the Milanese army kept the enemy engaged, the rest followed the course of the Aperto river in the Val Mulini, and after having crossed the Cosia they headed towards the southern walls of Como. Here the Milanese managed to surprise the guards guarding the gate and entered the city, where they massacred the few defenders and citizens, freed Landolfo da Carcano and set fire to the buildings. The Como army, entrenched on the slopes of the Baradello, saw the columns of smoke rising from the city and headed towards the Val Mulini, crossing the woods that covered the slopes of the hill. Passing through Borgo Vico, they entered the city, surprising the enemies intent on looting. The assault put the Milanese to flight, some of whom remained behind to cover the retreat to their comrades and were largely killed or taken prisoner. In the clash, the Milanese lost over a thousand men. Bishop Grimoldi distinguished himself as the main political and military leader of the Comaschi, able to "animate and support the courage of his men" and when he blessed the ships that took part in lake battles, "he sent them almost to a certain victory". [7] [6]

1119 siege of Como

The defeat suffered was not enough to make the Milanese desist from their intentions. A new general council was convened in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore where the citizens and nobles decided to renew hostilities, vowing to undertake to destroy the villages of Vico and Coloniola, located respectively to the west and north of the walled city in Como. Among the main proponents of the new oath was Arduino (sometimes called Arialdo or Arderico) degli Avogadri, a member of the Como diocese. It was perhaps thanks to his diplomatic work that Milan secured the support of the parish churches of Bellagio, Menaggio, Gravedona and Nesso and above all of the parish church of Isola, which included the strategic and fortified Isola Comacina, which has always been a thorn in the side of the Comaschi over the control of Lake Como. Bishop Guido Grimoldi sent embassies to the Milanese people, with the aim of making them desist from the war or, at least, to refrain from the oath to continue it until the complete destruction of Como, but without success. [8]

In April 1119 the islanders of Isola Comacina sailed with seven ships and landed an army in Laglio, from where the soldiers headed towards Cernobbio along wooded paths until they took up position north of the village, near the mouth of the Garovo stream. The Cernobbio garrison, warned by some local peasant or by the tower located on the Colma della Guardia, became aware of the presence of the enemy and sent messengers to ask reinforcements in Como, which sent a substantial number of knights to attempt an ambush. The cavalry took up position among the trees of the marshes near the mouth of the Breggia. In the meantime, the islanders aboard the seven ships disembarked more men, leaving only the crews aboard the ships; the soldiers went in search of their companions in the bush, believing they would find them looting. Some scouts then warned them of the presence of the enemy, but a part of them still wanted to continue and seek battle. As soon as they reunited with their companions, they were attacked by the Comaschi, who routed them, forcing them to flee in a rush towards the ships. When they reached the shores of the lake, they saw that their ships had moved away from the shore but, being afraid of being pursued by the enemy, they tried to reach them anyway, resulting in many drowning due to their armors weighing them down. [8] [9]

When the news of the defeat of their allies arrived, the Milanese decided to strengthen their party by forging new alliances. Milan, which through the peace of 1112 had secured an alliance with Pavia and Cremona, made further agreements with Crema, Monza, Bergamo, Brescia, Novara, Asti, Vercelli, Verona, Parma, Bologna, Guastalla, the cities of Liguria and the countryside of Biandrate. The Milanese, having obtained the reinforcements of the allied cities, returned with a sizeable army to Como and besieged the city together with the two fortified villages, supported by a naval blockade and by the raids of the islanders. Guido Grimoldi, however, once again proved to be a skilled general and managed to defend both settlements, exploiting in particular the two towers of Vico. During one of the numerous cavalry sorties of the Comaschi there was a duel between the Milanese Alberto de' Giudici and the Comasco Araldo (or Arnaldo) Caligno, in which the latter was killed. After a few days of siege, as there was no progress, the Milanese abandoned their operations. A truce was established between Como and Milan until August of the following year, the former thus had time to improve the fortifications at the gates, build shelters on the city walls, as well as swell their ranks and prepare twelve ships. [10]

Naval battles of Tremezzo and Cavagnola

In 1120 the Comaschi armed the flotilla and attacked Tremezzo, managing to take the village by surprise, sacking it and taking many prisoners. On the way back, however, the twelve ships of the islanders blocked their way, positioning themselves between the tip of Balbiano and Casate. The result was a battle in which the Comaschi managed to sink a large galley and captured two enemy ships, plus another one that had been sent to help the Terrazzani from Bellagio, forcing the islanders to retreat, while losing one ship in their side. Three days later Lezzeno was sacked. Encouraged by these victories, the Comaschi then decided to attack the Isola Comacina Island. Their ships managed to get close to the walls of the island, but as soon as they were within range they were targeted by stones and flaming arrows. Despite this, the Comaschi managed to land and destroy some ships moored to the walls, while others were dragged offshore and captured or sunk. It was not long before the villages of Campo, Sala and Colonno were attacked and burned. Here the Comaschi were initially repelled by the local soldiers, but in the end, thanks to their numerical superiority, they managed to surround them, forcing them to flee by swimming towards the Isola Comacina. Bellagio was then attacked, with the defenders being forced to take refuge in the castle. [11]

In September the Comaschi launched a night attack on the Torre della Cappella, located in a strategic position on the rocky promontory of Cavagnola, near Lezzeno. After reaching the tower, they climbed the walls of the fort with ladders and took the garrison by surprise, putting it to the sword. The islanders, however, were warned and sent some ships to rescue. The Comaschi then sent two ships to meet them with the order to pretend to accept battle and then retreat towards the Cavagnola, where they would be attacked by the bulk of the fleet. The islanders fell into the trap and passed the promontory, after which they were targeted by arrows, stones and burning pitch from the enemy ships, defending themselves until they had to retreat due to the risk of being surrounded. The Comaschi had in fact placed the ships in such a way as to prevent them from returning to the port of Isola. The island ships then set course for Varenna, the only escape route left, pursued by the enemy. Here they asked for help from the locals who, in parts gathered on the shore and in part remaining in defense of the mountain, gave support to the islanders by hitting the Comaschi with a hail of stones. An island ship took advantage of the confusion to try to return to the port of Isola but was chased by the large twin galleys Cristina and Alberga which reached it, forcing it to return to Varenna. The Comaschi then tried to land, but were repulsed by a deluge of stones thrown by their adversaries. After having set fire to the ships moored near the village, they attempted a new assault, after which the islanders retreated to Castle Vezio; at that point, judging the castle impregnable with the means available, they decided to return to Como after having plundered the village. They then attacked Lierna, whose inhabitants took refuge in the mountains and the defenders in the castle of the village. The Comaschi managed to capture it by setting fire to the top of the tower, on which some shrubs grew, thus causing the roof to collapse. [12] [13]

The islanders then warned the Milanese of the defeats suffered, and the latter sent them substantial reinfoircements. Embarking on the ships at night, they rowed silently to Como and attacked the enemy ships anchored in the port, sinking a large number of them. The Comaschi were confronted with the fait accompli and only managed to save some ships which they were later able to repair. A few days later the Milanese and the islanders attempted a new naval assault on the city. The Comaschi arranged the army on the shore of the lake and strenuously opposed the landing of the enemies, but visdomino Beltrando, a noble from Como, fell in the clash. In the meantime, some island ships bypassed the city by disembarking the men at the villages of Coloniola and Vico. The Milanese soldiers then attacked the enemy on all sides and although they were unable to enter Como, they sacked, devastated and burned everything around the city, except for the fortified places. [14]

On Lake Ceresio the Lugano fleet, allied with Milan, prevailed, also thanks to the betrayal of Arduino, an admiral from Como who defected to the Milanese. In order to recover the fleet that had fallen into enemy hands, Grimoldi organized an expedition by loading two ships, Crastina and Alberga, on oxcarts and having it brought from Lario to Ceresio by land. Then the boats were launched in the Ceresio, loaded with soldiers, reaching the enemy fleet at anchor and destroyed it at the end of a short and bitter battle. Finally, returning by land to the countryside near Melano, the ships were hidden by covering them with piles of sand. [7] [15]

Assault on Varese and the castle of Drezzo

In 1121 the Comaschi went overnight to Varese, which had remained loyal to Milan. The city was taken by surprise and sacked, the defenders were killed or taken prisoner and carried off to Como. Encouraged by this success, the next day they attacked the castle of Binago, in the Seprio, whose inhabitants initially tried to defend themselves, managing to kill the Comasco nobleman Arialdo Segalino da Vico, called Pandisegale, but after realizing the enemy forces were overwhelming, they were forced to flee. Binago was sacked and set on fire. Shortly afterwards the inhabitants of the nearby Vedano rushed to support those of Binago, which, however, had already fallen; while discussing on what to do, they were attacked by the enemy cavalry and put to flight. The third expedition was directed against Drezzo. The village was easily captured, having been abandoned by its inhabitants who had taken refuge in the strong castle on Monte Olimpino. The Comaschi, at the suggestion of Pagano Prestinari, shot flaming arrows and managed to set fire to some heaps of straw placed in the castle courtyard. The consequent fire forced the defenders to fight the flames in order not to suffocate, but this allowed the attackers to climb the now unguarded walls and enter the castle. The inhabitants, however, barricaded themselves in one of the two towers and opposed such resistance that they finally forced the people of Como to retreat. During the clashes Giovanni Paliaro (or Paleari), a Milanese who sided with the Comaschi, was killed by a stone thrown from the tower. On the way back to Como, the Comaschi were attacked by the militias of Ronago, who had sided with the defenders of the castle of Drezzo, but despite being taken by surprise, they managed to defeat the attackers, forcing him to retreat first to Ronago, then to Trevano, then to Olgiate and finally to a disorderly rout. [16]

Fall of Lavena

In 1122, just as the signing of the Concordat of Worms put an end to the conflict between the emperor and the pope, the ten-year war entered a stalemate. The Milanese secured the alliance of Lugano as well as the control of the castle of San Martino, particularly important for its strategic and almost impregnable position, as it was located on a hill; in the meantime they prepared to build some geminae ships (ships consisting of two hulls side by side, joined by a bridge) and longships at Lavena. As their city was scarcely fortified and fearing Como's reprisals, the people of Lugano took refuge in the castle of San Martino. The Comaschi decided to punish the Luganese but after setting off towards the Ceresio, they found the road blocked by the enemy, therefore they decided to occupy the valley of Melano. Here they began to build ships, stretched a chain at the entrance to the port and built wooden bastions on the shore to protect the vessels. After various skirmishes, the two fleets finally confronted each other in the stretch of lake between Bissone and Melide. The battle lasted until sunset and had an its outcome was indecisive; eventually the Milanese ships retreated towards Lavena. In the end, the inhabitants of Lavena asked the Comaschi for help, claiming that they had given themselves to the Milanese to avoid the sacking and destruction of the village. The Comaschi reconciled with them and eventually moved their fleet and army towards that village. For unknown reasons, even before the battle began, some Milanese ships withdrew towards the port of Lavena, abandoning the rest, which were forced to retreat after taking serious casualties. The port, however, was defended by a tower that did not allow ships to approach. The Comaschi then decided to set fire to the port and the ships by shooting arrows and fiery bullets at a distance and then retreated. The Como army in the meantime captured Lavena, but being unable to capture the castle of San Martino, withdrew after taking care to set the village on fire so as not to leave it intact in the hands of the enemy. The Lavenese then returned to ally themselves with the Milanese and carried out raids, throwing stones on the Comaschi wherever they found them. [17] [18]

Not long after, the Comaschi, having obtained some reinforcements from their city and neighboring villages, returned to besiege the castle. To overcome their resistance, since a frontal attack was impossible, the captain Giovanni Bono da Vesonzo, a native of Val d'Intelvi, went with some soldiers to the top of a nearby mountain, whose slopes were particularly steep and from which it was possible to dominate San Martino. After reaching the desired place, he had himself put in a large basket carrying a large amount of stones and made himself stick out, with a pole, beyond the peak that overlooked the fortress. Then he began to “bomb” the Luganese soldiers by throwing stones, in an experiment of "aerial warfare", while his companions shot arrows at the defenders. The stones prevented the Luganese from leaning over the towers and walkways of the walls and at the same time caused the roofs to collapse on the defenders. The Comaschi who remained at the foot of the mountain then launched an assault against the castle and the defenders, unable to defend themselves, had to surrender and hand over the fortress to the Comaschi, who showed no mercy to the garrison. [15]

The capture of Porlezza and the betrayal of Arduino degli Avogadri

The Lavenese and Luganese, the former having lost their homes and possessions, the latter fearing retaliation by the Comaschi, sent messengers to Milan complaining of the destruction of their village which had been caused by the choice to place the Milanese naval base there, and asked for more protection. The general council then decided to accept their requests by moving the base from Lavena to Porlezza, where during the winter months everything necessary to build new galleys was transported; by spring the ships were ready for a new military campaign. When the spring of 1123 came, the Milanese and the militias of their allied lakeside villages set about to besiege the castle of San Michele by land and water near the village of Cima, not far from Porlezza. The siege immediately proved difficult due the castle's good defenses and the lack of siege engines. The situation only worsened the next day, when it started raining heavily, making the Milanese camp a quagmire and swelling the river. Failing to make progress, the Milanese sent for the archbishop Olrico da Corte to induce the defenders to swear allegiance to him. Faced with the request for a surrender and the oath of loyalty to Milan, the Comaschi refused, covering him with insults. The Milanese were therefore forced to lift the siege. [19]

The garrison then asked the Comaschi for help, and they gathered reinforcements from the city and Val d'Intelvi with the aim of capturing Porlezza. To this end, towards December they divided the army into two group, one of which, composed of Comaschi, would march to Osteno and then embark and rejoin the defenders of the castle of San Michele, whereas the other, composed of the Intelvi soldiers, would have waited for the first in Melano so that Porlezza could be attacked on two sides at the same time. When the Intelvi troops had already set sail for Porlezza, the ships of the Milanese allies came to meet them from that village. The two flotillas clashed and after a long and uncertain battle the Terrazzani were forced to retreat to the port of Porlezza despite having inflicted heavy losses on the enemy; among the fallen there was the noble Alderamo Quadrio. The intelvani then went with the boats under the village and set fire to two enemy ships while the Como allies managed to capture the village without encountering much resistance. [20]

Not long afterwards, Arduino degli Avogadri from Como secretly went to Milan, offering to hand over the castle and the port of Melano in exchange for a large sum of money and protection for himself and his family; the Milanese accepted. Arduino then collected as many ships as possible at the port of Melano and began to make raids along the entire lake of Lugano without being opposed by the Milanese. He then sent envoys to Como announcing his progress and requesting more men for the Melano garrison. However, when the reinforcements arrived on the spot, Arduino had them arrested, undressed and imprisoned in his castle, releasing them only upon payment of a ransom. The people of Como, having discovered his betrayal, dismantled the large ships Cristina and Alberga and transported them on ox-drawn carts to Ripa, where they were reassembled and put into the water. Having taken to Lavena they managed to capture two enemy ships, then they went to the castle of San Martino and besieged it. The castle garrison soon fled to the surrounding mountains. The four ships then set sail for Melano which they easily occupied as Arduino had fled. [21]

Assault on Isola Comacina

Shortly before Christmas, the Milanese decided to attack the castle of Pontegana, not far from Balerna, whose position allowed control of the road that connected Como to Lugano as well as access to the Valle di Muggio. The fortress was defended by a moat and an embankment on the western side, which sloped gently downstream, while on the eastern side the sheer wall made it inaccessible. Given the difficulty of seizing it with an assault and not wanting to attempt a long siege, the Milanese decided to bribe the castellan, Giselberto (or Gilberto) Clerici, who after being lavishly paid retired to the parish of Arcisate to protect himself from revenge of his compatriots. Having obtained the castle, the Milanese drove out all those who were linked to Giselberto, except the peasants who had to give an oath of loyalty. In those same days the parish of Gravedona decided to abandon its alliance with the parishes of Bellagio, Menaggio, Nesso and Isola and allied itself with Como. [22] [23]

To compensate for the loss of Pontegana, the Comaschi decided to launch another naval attack on the Isola Comacina. They landed on the island and after a bitter fight with the islanders near the gates of the walls, they entered the town and sacked it while the defenders were forced to either barricade themselves in the castle or try to escape by swimming towards Sala and Spurano. During the clashes the Comasco leader Oldrado was killed by the spear of Alberto Natale. After having collected a huge booty, the Comaschi dedicated themselves to the destruction of the island, dismantling its fortifications and setting all buildings on fire, so that in the future it would no longer be able to defend itself, except for the castle which they were unable to take. When the news arrived that the terrazzani, despite the bitter defeat of Isola, were again gathering militias against them, the Comaschi decided to prevent them by landing in Campo, destroying the newly built walls and subjecting it to a new looting. Then the Comaschi sent an embassy to the island asking the defenders of the castle to surrender because being unable to receive the help of the Milanese, they had no hope of resisting for a long time having against not only the city of Como but also the Val d'Intelvi, Lugano and the villages of Ceresio as well as Valtellina. The islanders, however, did not want to bow to the dominion of Como. The Comaschi then attacked and captured Mezzegra and Colonno and later Menaggio, where they broke down the castle door with a ram and set it on fire. [24]

Operations near Cantù and sieges of Como in 1124 and 1125

In 1124 the comune of Cantù joined the anti-Como coalition. At the beginning of the year the Canturini attacked and sacked the villages of Lipomo, Albate and Trecallo, and the Comaschi were forced to abandon the siege of the castle of Pontegana to go against them. The Canturini, led by Gaffuro, ambushed the enemy by placing themselves in the woods near Trecallo, on the sides of the road that connected Cantù and Albate. In the battle that followed the Comaschi won, Gaffuro was killed and according to the story of Poeta Cumano , "the Acquanegra stream ran red". The Canturini then retreated towards the Sagrada canal, but the Comaschi were quicker and managed to occupy the ford after having dispersed a weak group of defenders who fled towards the Acquanegra marshes. Here the Canturini were again attacked by a group of Comaschi who guarded the place and after returning to the ford they were definitively surrounded and in the ensuing clash they lost sixty men. The victors then headed against Cantù itself but the Canturini made a sortie to avert the siege, inflicting serious losses on the Comaschi. [15] [25]

The Canturini then joined forces with the Terrazzani and together sent embassies to ask for Milanese intervention to support them, in light of the recent and heavy defeats. The Milanese gathered their army and reinforced it with men from the allied cities, sending it to Como. After a brief battle at the gates of the city, the Milanese forced the people of Como to entrench themselves behind the walls. In the meantime, the lakeside city was subjected to yet another naval blockade by the Terrazzani. As the situation was now critical, the Comaschi decided to try to break through the blockade in order to reach their allies in Gravedona and Valtellina. They succeeded, and returned after collecting as many ships as possible from the allies. This time, however, facing them near the narrow between the hill of Lavedo and Lezzeno, they found both the ships of the Terrazzani and of Lecco, allies of the Milanese. A naval clash ensued at the end of which the Comaschi again managed to break through the enemy blockade, but the Terrazzani in turn forced the enemy to move towards the Isola Comacina, where the island ships were waiting for him. Despite being surrounded and now trapped, the Comaschi managed once again to defeat the enemy and return to Como after having seriously damaged the two major ships of the adversaries. [26]

To try to lift the siege, the Comaschi attempted a sortie against Cantù and Mariano which, however, had a disastrous outcome. Not having obtained any results in the south, the Comaschi decided to attack the Isola Comacina again with the aim of capturing the castle and dismantling it once and for all. To this end, they cut down many of the island's olive and fruit trees and made bundles with the wood obtained, which they leaned against the walls of the fortress and then set fire to it. However, the defenders managed to resist, so the Comaschi began to target the castle with catapults mounted on the wooden platforms of the ships that surrounded the island. After the death of Pagano Beccaria, pierced by an arrow in one eye, realizing that neither the fire nor the catapults had managed to get the better of the castle of the island, the Comaschi finally decided to retire. The Milanese did the same, however, as they were unable to enter Como. The campaign of 1124 ended with the capture of Nesso and its castle by the Comaschi. [27]

In 1125 the Milanese, after having prepared thirty galleys in Lecco, returned to besiege Como by land and water. Despite having surrounded the city and the villages of Vico and Coloniola, the Comaschi managed to drive them away from the walls with a sortie. Meanwhile, on the lake, when the Comaschi saw the enemy fleet cross the gap between Careno and Torriggia they arranged themselves in a long line that blocked the gap between Moltrasio and Torno. The two fleets headed against each other but the Ratto, a small and fast ship from Como, preceded all the others and upon reaching the enemy, was soon surrounded and rammed. During the battle, the people of Como managed to capture an island ship on which the hated Arialdo Paradiso and Alberto Natale were taken prisoner. In the afternoon the Lecco fleet, after having lost six ships by boarding and others by sinking, withdrew and set sail for the Isola Comacina. Having learned of the defeat at Torno and having suffered too many losses in the siege, the Milanese retreated once again. After the Milanese retreat, the Comaschi set fire to Vertemate, Guanzate and Cirimido to avenge the death of Beltramo Bracco, who had been mortally wounded in a raid. The small garrison of those villages, led by the nobles Alberto and Manfredo and heavily outnumbered, took refuge in a nearby church but the Comaschi set fire to it, forcing them to leave. On the way back, the Comaschi were surrounded by the Vertematesi but managed to break through the encirclement and disperse them. They then besieged the castle of the village using siege engines and crossbows until they captured it and massacred defenders and civilians alike. [27]

Death of Guido Grimoldi and decline of Como's fortunes

On 27 August 1125 (according to other sources, on 17 August) Guido Grimoldi died, being buried in the Basilica di Sant'Abbondio. The death of the warrior-bishop turned the fortunes of the war for the worse for the city of Como. In its place the new emperor Henry V of Franconia appointed the prudent Ardizzone I, who unlike his predecessor did not have the qualities of a leader. [28] [15]

The first of the misfortunes for the people of Como occurred in that same year. Although bishop Ardizzone had tried to dissuade the Comaschi from such a punitive expedition, they decided to aim for the destruction of Mariano, a trading village allied with the Milanese, which a few months earlier, together with the Canturini, had inflicted on them a humiliating defeat. After carrying out raids in the countryside of Vighizzolo and Mariano, the Comaschi, loaded with loot, marched towards the latter village. Then the Marianese, together with the Canturini, the Milanese and militias of the Martesana, who until then had left them free to loot in order to lure them into a trap, caught them in an ambush, defeating them and killing many of their best knights. A group of Como knights led by Arnaldo Caligno charged the enemy trying to save the life of Mulizzone (called Bando), a knight who was his friend, but the group was soon surrounded and annihilated; both fell and together with them Ruggero da Fontanella, Pandolfo da Canonica, Equitaneo Rusca and Eutichio della Casella, all coming from some of the major Como families. As if that were not enough, a few days later Arduino degli Avogadri, considering that the Comaschi had no chance of victory, handed over the castle of Lucino to the Milanese; his brother Ottone, who remained loyal to the Comaschi, tried to recover it with a group of knights but was killed by a javelin in the chest. [29]

The people of Como then tried their luck on the lake, heading with their ships and those of Gravedona towards the Torre della Cappella, which in the meantime had been rebuilt by the Terrazzani. Five Lecco ships tried to reach the tower to unload supplies but were intercepted by the Comaschi. In the clash that followed the Como flagship, the Grifo, managed to ram its counterpart from Lecco which, however, managed to dock and disembark the men, aided by the garrison of the tower. Another ship from Como ran aground and the crew was captured and imprisoned after a fierce fight. At that point the Comaschi and Gravedonese disengaged and returned to Como empty-handed.

Towards the end of autumn Galicia, a noblewoman daughter of Alterio from Isola Comacina, decided, together with her children, to visit her husband Giordano Visdomini, who owned the castle of Domofole in Valtellina. The Comaschi had her escorted by two warships full of soldiers. During the return voyage, the two ships headed towards the Lecco branch of the lake in the hope of making loot. During the evening the Comaschi tried to plunder the surrounding villages but without success, and eventually landed in the night near Malgrate. The next morning the two ships were identified by the inhabitants of the villages of the Lecco branch, who embarked and tried to surround the enemy. The Comaschi tried to escape but found themselves against the wind and were unable to land at Mandello so they had to head north until, being chased, they were forced to dock near the nearby Bellano, which was however an enemy village. As soon as the local garrison spotted them, they ran to attack them and took them all prisoner. The prisoners later managed to escape through an underground passage and take refuge in the Val d'Intelvi.

Milanese invasion of Valtellina

After all these setbacks, the Comaschi managed to obtain the Orezia Tower in Dervio thanks to the betrayal of a local Milanese governor, called Corrado; it was said that to signal the moment in which the Comaschi should enter the fortress and get rid of the present garrison, he had a red banner with a white cross raised and this was one of the first uses of the Como municipal flag in history. Since the Torre di Orezia was of great strategic importance, the Comaschi defended it with a larger garrison than the previous one and basing the Lupo in Dervio, a ship that in the following weeks became famous for its raids against the Terrazzani; one day, however, when returning from yet another raid, the ship was surrounded by enemy boats and the Comaschi were forced to run it aground near Dervio, where they were attacked and killed or taken prisoner by the soldiers who had hidden in the surrounding woods. To secure the release of their prisoners and the Lupo, the Comaschi had to surrender the Torre di Orezia. The Milanese then used it as a bridgehead to carry out raids in Valtellina, fruitlessly opposed by the locals. Morbegno, Delebio, the castle of Domofole and many other minor villages were sacked and burned. The Valtellinesi then gathered an army and attacked the enemy near Berbenno, but were again defeated. On the eastern side of the valley Egano (or Eginone) Visconti Venosta, former lord of Bormio and Poschiavo, took the opportunity to extend his domain by capturing the parish of Mazzo and a large part of the parish of Tirano. Shortly afterwards the Milanese captured the castle of Malgrate, in front of Lecco, with a surprise night attack. [30] [31]

Ambush at Concorezzo and conquest of Lake Lugano

In 1126 the Como militias, on the advice of Alberico, castellan of Bregnano, marched to a crossroads near Concorezzo, very popular with those who went to sell or buy goods at the city market. Once on the spot they hid with their horses in a wood near the crossroads, hoping to seize a large booty. In the meantime, Alberico sent messengers to warn the Milanese of the movements of the Comaschi. The latter, after having carried out the raid without obtaining anything, noticed too late the red-crossed white banners of the Milanese and fled. The rearguard remained to cover the retreat but was defeated, and thirty knights were killed or wounded, among them nobles such as Gualdrado de Piro and his son, Goffredo called the Valid, Pietraccio da Fontanella, Arnaldo da Vertemate, Giovanni Visdomini and Marco Azzola. Alberico himself had the audacity to fight the Como knights and was killed by a man named Rampagio. The Milanese took advantage of the rout of the Comaschi to march until a quarter of a mile from the walls of Como. There they founded a village protected by a palisade and moat, which they called Villanova, and above the village of San Martino they built a wooden castle with two twin towers, which they called Castelnuovo (Zerbio castle), installing a garrison of soldiers from Monza, then returning to the city. The Comaschi made a sortie with which they managed to capture Villanova, taking some prisoners, but not Castelnuovo. The Milanese replaced the Monzese garrison with one made up of soldiers from Cremona. Towards the end of that year's campaign, the Comaschi, in a new sortie, defeated the Cremonese who had carelessly pushed themselves under the city walls, then captured and burned Castelnuovo. [32] [33]

The Milanese then decided once and for all to take all the lands around Lake Lugano from the Como faction. They ordered the people of Lodi, who after the destruction of their city in 1111 were still their subjects, to supply men for the enterprise, then they went with them to Lavena, led by the archbishop Anselmo V Pusterla which had recently succeeded Olrico da Corte. The Comaschi placed their militias, led by Arnaldo, castellan of the fortress of Albaredo, near the river Tresa, at the foot of Mount Castellano, where they built a strong bastion to defend. The Milanese, however, decided to attack them by climbing the slopes of the mountain and in the battle that followed they attacked them first from above by rolling boulders, then on the side, inflicting a crushing defeat after which the Comaschi abandoned all the villages on that lake. [34]

Destruction of Como

In 1127 the Milanese hired Genoese carpenters and Pisan engineers to build siege engines and ordered the Lecchese to supply the necessary timber. Meanwhile, their army, swollen by many soldiers coming from Pavia, Novara, Vercelli, Alba, Albenga, Asti, Cremona, Mantua, Piacenza, Parma, Modena, Bologna, Ferrara, Vicenza and from Garfagnana, marched again on Como and rebuilt Castelnuovo, then set up camp in front of the city, also carrying out a naval blockade on the lake. The Milanese then built four large siege towers in wood, covered with a wicker trellis in turn covered with wet leather to reduce the possibility of fire. They also made two battering rams covered in the same way, each of which was placed in the middle of each pair of towers and four ballistae, also covered. At the end of the work, amidst the jubilation and the shouts of the soldiers, one of the two pairs of towers was dragged towards the western walls, the other to the southern ones, covered by the launch of ballistae and by the arrows shot by the archers who occupied the towers themselves and the surrounding field. Meanwhile, the engineers worked hard to fill the moat and place wooden beams and bundles to allow the towers and rams to approach the walls. On the night of the first day of the siege, the Comaschi attempted a sortie which however proved fruitless, and in which Lamberto Rusca was mortally struck by an arrow. The following day the Como consuls realized that the city was by now indefensible, and they had the citizens and part of the soldiers ferried together with their most precious possessions to the fortified village of Vico. In the afternoon the defenders attempted a last desperate sortie which was not successful. The Milanese, as evening had come and fearing that only a part of the Comaschi had come out to face them, waited the following morning before entering the city. [35]

On 27 August the Milanese, probably urged by Archbishop Anselmo, made contact with the Como clerics in order to agree on a peace. In addition to being spared their lives, the Comaschi were granted the maintenance of all movable and immovable property, but they would have to destroy the city of Como, including the villages of Vico and Coloniola, with the sole exception of the sacred buildings. The major exponents of the Como clergy and nobility approved these harsh terms by taking an oath, and the peace was transcribed and signed in two identical copies. The Poeta Cumano , a contemporary writer who chronichled the war, stated in his work that the Milanese soldiers did not respect the terms established by their nobility and plundered everything, even taking away the servants of the Como nobles; however, it must be considered that this is a far from neutral source. The dismantling of Como took many months and only ended on 26 or 28 March 1128. [36]