Weser Renaissance is a form of Northern Renaissance architectural style that is found in the area around the River Weser in central Germany and which has been well preserved in the towns and cities of the region.

Weser Renaissance is a form of Northern Renaissance architectural style that is found in the area around the River Weser in central Germany and which has been well preserved in the towns and cities of the region.

Between the start of the Reformation and the Thirty Years War the Weser region experienced a construction boom, in which the Weser, playing a significant role in the communication of both trade and ideas, merely defined the north–south extent of a cultural region that stretched westwards to the city of Osnabrück and eastwards as far as Wolfsburg. Castles, manor houses, town halls, residential dwellings and religious buildings of the Renaissance period have been preserved in unusually high density, because the economy of the region recovered only slowly from the consequences of the Thirty Years War and the means were not available for a baroque transformation such as that which occurred to a degree in South Germany.

The term, coined around 1912 by Richard Klapheck, suggested that the Renaissance along the Weser independently developed its own distinct style. Max Sonnen, who used the newly coined term in 1918 in his book Die Weserrenaissance, classified buildings, without regard for the circumstances of their historical background, but from a purely formal perspective in order to derive a history of the development of the style. The notion of a regional renaissance in the sense of an autonomous cultural phenomenon was based on a nationalistic mindset that had arisen since the end of the 19th century, in which things provincial also had their place in establishing identity (other examples include German Sondergotik, Rhenish or Saxon Romanesque architecture). [1]

In 1964, Jürgen Soenke and the photographer, Herbert Kreft, presented an inventory of Renaissance buildings, which also went under the title of Die Weserrenaissance. In its closing remarks it said: This architecture is rooted in the landscape in which it stands. It is folksy because those who created it [...] came from the people. The Weser Renaissance is, simply, folk art. For Soenke an autochthonous (indigenous) evolution of architectural style lay hidden behind its common features. His work, that appeared in six editions up to 1986, helped to give this art-historical concept a level of popularity that went far beyond the realm of the specialist and became a kind of popular trademark. [2]

The term Weser Renaissance gained international recognition thanks to Henry-Russel Hitchcock, who used it in his German Renaissance Architecture of 1981, although he stressed its distinctive regional features rather less and pointed out its more significant linkages with the overall historical development of Renaissance architecture. In more recent times the idea of a regional cultural identity, that did not exist in the Early Modern Period, was criticised in research by the Weser Renaissance Museum at Brake Castle, which had been founded in 1986. This research highlighted the carriers of cultural transference, such as the architectural drawing business, non-local architects, pan-regional builders and the obligatory, Europe-wide requirements of court fashion.

The hallmark of aristocratic building activity in the 16th century was the transformation of a medieval castle, the Burg, into a royal residence or Schloss. Initially these were often built with two wings, but later the enclosed courtyard, with its wings joined in the corners by imposing towers with flights of stairs, became the preferred layout for the homes of the aristocracy in the Weser region during the course of the 16th century, a form of building that was soon also adopted by its lesser noblemen. The characteristic Zwerchhaus (Middle High German: twerh = quer i.e. across or lateral) with so-called welsch (i.e. Italian) gables was particularly well suited as a symbol of power, because on castles like those at Detmold, Celle or Bückeburg, which were surrounded by high ramparts, they could be seen from a long way off. In addition to four-sided castles, there were also castles with three wings, either geometrically fully enclosed, like the Wewelsburg, or opening onto the castle farmyard as at Schwöbber. Even double-winged and single-winged buildings were included in the repertoire of castle architecture along the Weser.

These aristocratic designs were not only embraced by the lesser nobles; middle-class builders also copied the new forms of building in order to show off their growing social influence. Town halls, like those in Celle and Lemgo, were designed with gables along the sides and sometimes faced with an entire renaissance façade, as occurred in Bremen. From Nienburg, to Minden, Hamelin and Höxter, Hannoversch Münden and Einbeck magnificent townhouses appeared, that were often distinguished by their great gateway into the inner hall. Other important architectural features of the Weser Renaissance style are the ornately decorated gables, the use so-called Bossenquader or bossage stone, the alcoves (Standerker, Ausluchten or Utluchten) and double windows. [3]

Church builders were also eager to explore new architectural designs. By elevating the position of the pulpit and placing it immediately opposite to and facing the pews, the importance of the spoken word within the Christian faith was also visible from the layout of the church interior. The castle chapels of Celle and Bückeburg are also clear examples of this arrangement as are the important parish churches of Wolfenbüttel and Bückeburg. Protestant art experienced a high point in the Weser region under the Schaumburg prince, Ernest, who at the beginning of the 17th century, had the Stadthagen Mausoleum and tomb built by Adriaen de Vries, which recalled the Florentine Renaissance. At the same time the goldsmith, Anton Eisenhoit created the altar decorations for the Catholic prince-bishop, Dietrich von Fürstenberg, and the sculptor Heinrich Gröninger, whose monumental tomb lies in Paderborn Cathedral.

By the Thirty Years War over 30 builders had worked in the Weser Renaissance style.

Lower Saxony is a German state in northwestern Germany. It is the second-largest state by land area, with 47,614 km2 (18,384 sq mi), and fourth-largest in population among the 16 Länder federated as the Federal Republic of Germany. In rural areas, Northern Low Saxon and Saterland Frisian are still spoken, albeit in declining numbers.

The Weser is a river of Lower Saxony in north-west Germany. It begins at Hannoversch Münden through the confluence of the Werra and Fulda. It passes through the Hanseatic city of Bremen. Its mouth is 50 km (31 mi) further north against the ports of Bremerhaven and Nordenham. The latter is on the Butjadingen Peninsula. It then merges into the North Sea via two highly saline, estuarine mouths.

Detmold is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, with a population of 73,969. It was the capital of the small Principality of Lippe from 1468 until 1918 and then of the Free State of Lippe until 1947. Today it is the administrative center of the district of Lippe and of the Regierungsbezirk Detmold. The Church of Lippe has its central administration located in Detmold. The Reformed Redeemer Church is the preaching venue of the state superintendent of the Lippe church.

Lemgo is a small university town in the Lippe district of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

The Weser Uplands is a hill region in Germany, between Hannoversch Münden and Porta Westfalica, along the river Weser. The area reaches into three states, Lower Saxony, Hesse, and North Rhine-Westphalia. Important towns of this region include Bad Karlshafen, Holzminden, Höxter, Bodenwerder, Hameln, Rinteln, and Vlotho.

Bad Salzuflen is a town and thermal spa resort in the Lippe district of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. At the end of 2013, it had 52,121 inhabitants.

Beverungen is a town in Höxter district in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Stadthagen is the capital of the district of Schaumburg, in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated approximately 20 km east of Minden and 40 km west of Hanover. The city consists of the districts Brandenburg, Enzen-Hobbensen, Hörkamp-Langenbruch, Krebshagen, Obernwöhren, Probsthagen, Reinsen and Wendthagen-Ehlen. Earlier, there were also the districts Habichhorst, Bruchhof, Blyinghausen, Enzen and Hobbensen.

The Süntel (help·info) is a massif in the German Central Uplands that is up to 437.5 m above sea level (NN). It forms part of the Weser Uplands in Lower Saxony southwest of Hanover and north of Hamelin.

The Solling-Vogler Nature Park is a nature park in South Lower Saxony in Germany. It has an area of 52,000 hectares (200 sq mi) and was established in 1966.

The Weser Uplands-Schaumburg-Hamelin Nature Park lies on the northern edge of the German Central Uplands where it transitions to the North German Plain, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) southwest of Hanover. The sponsor of the nature park, which was founded in 1975, is the state of Lower Saxony. The park extends along the Weser valley between Rinteln and Hamelin and includes parts of the Schaumburg Land, Calenberg, Lippe and Pyrmont Uplands from Bad Nenndorf in the north to Bad Pyrmont in the south, Bückeburg and Bad Eilsen in the west and Bad Münder and Osterwald in the east. Its highest elevation is in the Süntel hills.

The Road of Weser Renaissance is a well-known tourist route in North Germany. As a cultural route it links famous architectural monuments of the Weser Renaissance period in the 16th and early 17th centuries.

The German Fairy Tale Route is a tourist attraction in Germany originally established in 1975. With a length of 600 kilometres (370 mi), the route runs from Hanau in central Germany to Bremen in the north. Tourist attractions along the route are focused around the brothers Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm, including locations where they lived and worked at various stages in their life, as well as regions which are linked to the fairy tales found in the Grimm collection, such as The Town Musicians of Bremen. The Verein Deutsche Märchenstraße society, headquartered in the city of Kassel, is responsible for the route, which travellers can recognize with the help of road signs depicting the heart-shaped body and head of a pretty, princess-like creature.

Count Simon VI of Lippe was an imperial count and ruler of the County of Lippe from 1563 until his death.

The Wolfsburg is medieval lowland and water castle in North Germany that was first mentioned in the records in 1302, but has since been turned into a Renaissance schloss or palace. It is located in eastern Lower Saxony in the town of Wolfsburg named after it and in whose possession it has been since 1961. The Wolfsburg developed from a tower house on the River Aller into a water castle with the character of a fortification. In the 17th century it was turned into a representative, but nevertheless defensible palace that was the northernmost example of the Weser Renaissance style. Its founder and builder was the noble family of von Bartensleben. After their line died out in 1742 the Wolfsburg was inherited by the counts of Schulenburg.

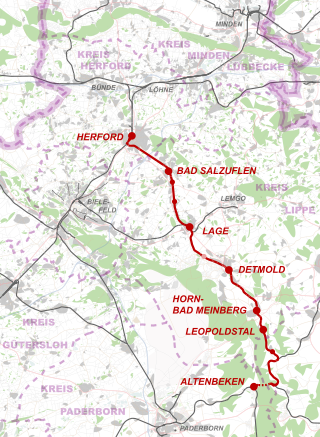

The Herford–Himmighausen railway is a 48 km-long line from Herford via Detmold to Himmighausen and is a single-track and electrified main line. It is located in Ostwestfalen-Lippe in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and is part of Deutsche Bahn’s Münster-Ostwestfalen regional network (MOW), which has its headquarters in Münster. In Herford this route is known as the Lippische Bahn. The line from Herford to Detmold was built by the Cologne-Minden Railway Company.

Vlotho station is a station on the Elze–Löhne railway in the east Westphalian town of Vlotho in the Herford district of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The line connects Löhne, Hamelin and Hildesheim and is served by the Weser-Bahn service. All buildings including the entrance building have not been used for their original purposes since 1992 and they are no longer owned by Deutsche Bahn.

Georg Ulrich Großmann is a German art historian. He was general director of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg.