Barium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ba and atomic number 56. It is the fifth element in group 2 and is a soft, silvery alkaline earth metal. Because of its high chemical reactivity, barium is never found in nature as a free element.

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to its heavier homologues strontium and barium. It is the fifth most abundant element in Earth's crust, and the third most abundant metal, after iron and aluminium. The most common calcium compound on Earth is calcium carbonate, found in limestone and the fossilised remnants of early sea life; gypsum, anhydrite, fluorite, and apatite are also sources of calcium. The name derives from Latin calx "lime", which was obtained from heating limestone.

William Withering FRS was an English botanist, geologist, chemist, physician and first systematic investigator of the bioactivity of digitalis.

The alkaline earth metals are six chemical elements in group 2 of the periodic table. They are beryllium (Be), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), strontium (Sr), barium (Ba), and radium (Ra). The elements have very similar properties: they are all shiny, silvery-white, somewhat reactive metals at standard temperature and pressure.

Fluorite (also called fluorspar) is the mineral form of calcium fluoride, CaF2. It belongs to the halide minerals. It crystallizes in isometric cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon.

Calcite is a carbonate mineral and the most stable polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scratch hardness comparison. Large calcite crystals are used in optical equipment, and limestone composed mostly of calcite has numerous uses.

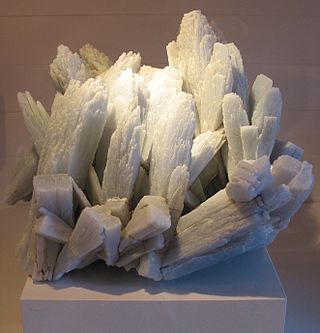

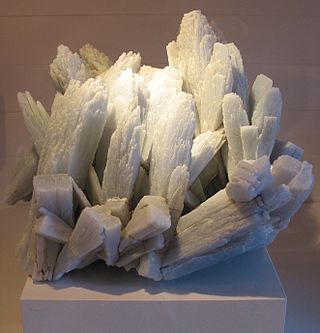

Baryte, barite or barytes ( or ) is a mineral consisting of barium sulfate (BaSO4). Baryte is generally white or colorless, and is the main source of the element barium. The baryte group consists of baryte, celestine (strontium sulfate), anglesite (lead sulfate), and anhydrite (calcium sulfate). Baryte and celestine form a solid solution (Ba,Sr)SO4.

Strontianite (SrCO3) is an important raw material for the extraction of strontium. It is a rare carbonate mineral and one of only a few strontium minerals. It is a member of the aragonite group.

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral and one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate, the others being calcite and vaterite. It is formed by biological and physical processes, including precipitation from marine and freshwater environments.

Stibnite, sometimes called antimonite, is a sulfide mineral with the formula Sb2S3. This soft grey material crystallizes in an orthorhombic space group. It is the most important source for the metalloid antimony. The name is derived from the Greek στίβι stibi through the Latin stibium as the former name for the mineral and the element antimony.

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Selenite, satin spar, desert rose, and gypsum flower are crystal habit varieties of the mineral gypsum.

Anglesite is a lead sulfate mineral with the chemical formula PbSO4. It occurs as an oxidation product of primary lead sulfide ore, galena. Anglesite occurs as prismatic orthorhombic crystals and earthy masses, and is isomorphous with barite and celestine. It contains 74% of lead by mass and therefore has a high specific gravity of 6.3. Anglesite's color is white or gray with pale yellow streaks. It may be dark gray if impure.

Anhydrite, or anhydrous calcium sulfate, is a mineral with the chemical formula CaSO4. It is in the orthorhombic crystal system, with three directions of perfect cleavage parallel to the three planes of symmetry. It is not isomorphous with the orthorhombic barium (baryte) and strontium (celestine) sulfates, as might be expected from the chemical formulas. Distinctly developed crystals are somewhat rare, the mineral usually presenting the form of cleavage masses. The Mohs hardness is 3.5, and the specific gravity is 2.9. The color is white, sometimes greyish, bluish, or purple. On the best developed of the three cleavages, the lustre is pearly; on other surfaces it is glassy. When exposed to water, anhydrite readily transforms to the more commonly occurring gypsum, (CaSO4·2H2O) by the absorption of water. This transformation is reversible, with gypsum or calcium sulfate hemihydrate forming anhydrite by heating to around 200 °C (400 °F) under normal atmospheric conditions. Anhydrite is commonly associated with calcite, halite, and sulfides such as galena, chalcopyrite, molybdenite, and pyrite in vein deposits.

Alstonite, also known as bromlite, is a low temperature hydrothermal mineral that is a rare double carbonate of calcium and barium with the formula BaCa(CO

3)

2, sometimes with some strontium. Barytocalcite and paralstonite have the same formula but different structures, so these three minerals are said to be trimorphous. Alstonite is triclinic but barytocalcite is monoclinic and paralstonite is trigonal. The species was named Bromlite by Thomas Thomson in 1837 after the Bromley-Hill mine, and alstonite by August Breithaupt of the Freiberg Mining Academy in 1841, after Alston, Cumbria, the base of operations of the mineral dealer from whom the first samples were obtained by Thomson in 1834. Both of these names have been in common use.

Barytocalcite is an anhydrous barium calcium carbonate mineral with the chemical formula BaCa(CO3)2. It is trimorphous with alstonite and paralstonite, that is to say the three minerals have the same formula but different structures. Baryte and quartz pseudomorphs after barytocalcite have been observed.

Anglezarke is a sparsely populated civil parish in the Borough of Chorley in Lancashire, England. It is an agricultural area used for sheep farming and is also the site of reservoirs that were built to supply water to Liverpool. The area has a large expanse of moorland with many public footpaths and bridleways. The area is popular with walkers and tourists; it lies in the West Pennine Moors in Lancashire, sandwiched between the moors of Withnell and Rivington, and is close to the towns of Chorley, Horwich and Darwen. At the 2001 census it had a population of 23, but at the 2011 census the population was included within Heapey civil parish. The area was subjected to depopulation after the reservoirs were built.

Rampgill mine is a disused lead mine at Nenthead, Alston Moor, Cumbria, England UK Grid Reference: NY78184351

Serpierite (Ca(Cu,Zn)4(SO4)2(OH)6·3H2O) is a rare, sky-blue coloured hydrated sulfate mineral, often found as a post-mining product. It is a member of the devilline group, which has members aldridgeite (Cd,Ca)(Cu,Zn)4(SO4)2(OH)6·3H2O, campigliaite Cu4Mn2+(SO4)2(OH)6·4H2O, devilline CaCu4(SO4)2(OH)6·3H2O, kobyashevite Cu5(SO4)2(OH)6·4H2O, lautenthalite PbCu4(SO4)2(OH)6·3H2O and an unnamed dimorph of devilline. It is the calcium analogue of aldridgeite and it is dimorphous with orthoserpierite CaCu4(SO4)2(OH)6·3H2O.

Hokutolite is the only mineral named after a Taiwanese place among the more than 4,000 naturally occurring minerals in the world. Hokutolite is a rare mineral containing radioactive radium elements generated by the hot spring environment, and is currently found only in Beitou Hot Spring in Taipei City, and Tamagawa Hot Spring in Akita Prefecture, Japan. In Japan, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology has designated it as a "Special Natural Monument". In Taiwan, it is designated as a "Natural Cultural Landscape", and the Taipei City Government has designated a natural reserve in the Beitou River upstream of the Beitou Hot Spring Museum.