The composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was a Catholic, and the Church played an important role in his life.

The composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was a Catholic, and the Church played an important role in his life.

Mozart's parents (Leopold Mozart and Anna Maria Mozart) were Catholics and raised their children religiously, insisting upon strict obedience to the requirements of the Church. [1] They encouraged family prayer, fasting, the veneration of saints, regular attendance at mass, and frequent confession. [2]

Leopold Mozart continued to urge strict observance upon Wolfgang even when the latter had entered adulthood. In 1777, he wrote to his wife and son, who at the time were on their journey to Paris:

Is it necessary for me to ask whether Wolfgang is not perhaps getting a little lax about confession? God must come first! From His hands we receive our temporal happiness; and at the same time we must think of our eternal salvation. Young people do not like to hear about these things, I know, for I was once young myself. But, thank God, in spite of all my youthful foolish pranks, I always pulled myself together. I avoid all dangers to my soul and ever kept God and my honor and the consequences, the very dangerous consequences, before my eyes. [3]

By "very dangerous consequences", Leopold was most probably referring to a specific doctrine of Catholicism, namely that persons who die in a state of mortal sin will experience eternal punishment in hell.

Leopold extended another important element of Catholic belief—the existence of earthly miracles as signs from God—to the case of his son, whose abilities he considered to have a divine origin. In 1768, he wrote to his friend Lorenz Hagenauer, describing his son as

a miracle, which God has allowed to see the light in Salzburg. ...And if it is ever to be my duty to convince the world of this miracle, it is so now, when people are ridiculing whatever is called a miracle and denying all miracles. ...But because this miracle is too evident and consequently not to be denied, they want to suppress it. They refuse to let God have the honor. [4]

As a teenager, Mozart went on tours of Italy, accompanied by his father. During the first of these, Leopold and Wolfgang visited Rome (1770), where Wolfgang was awarded the Order of the Golden Spur, a form of honorary knighthood, by Pope Clement XIV. The papal patent for the award said:

Inasmuch as it behoves the beneficence of the Roman Pontiff and the Apostolic See that those who have shown them no small signs of faith and devotion and are graced with the merits of probity and virtue, shall be decorated with the honours and favors of the Roman Pontiff and the said See. (4 July 1770) [5]

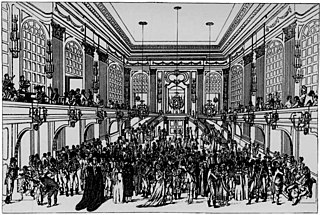

The following day Mozart received his official insignia, consisting of "a golden cross on a red sash, sword, and spurs," emblematic of honorary knighthood. [6] The papal patent also absolved the awardee from any previous sentence of excommunication (unnecessary in Mozart's case) and stated "it is our wish that thou shalt at all times wear the Golden Cross." In the 1777 painting (shown here) known as the "Bologna Mozart", Mozart is indeed shown wearing his knightly insignia.

Mozart's Golden Spur decoration was the source of an unpleasant incident in October 1777, when he visited Augsburg during the job-hunting tour (1777–1779) that ultimately took him to Paris. Following the advice of his father, [7] Mozart wore his insignia in public, and in particular to a dinner arranged by a young aristocrat named Jakob Alois Karl Langenmantel. Langenmantel and his brother-in-law teased Mozart mercilessly about the insignia, and Mozart ultimately was moved to reply very sharply and eventually depart. [8] Thenceforth Mozart showed considerably more caution in wearing his decoration. [7]

Matrimony is a sacrament of the Catholic Church, and Mozart was wedded in a Church ceremony. His bride was Constanze Weber; the two were married on 4 August 1782 in a side chapel of St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna where they lived. [9]

Mozart joined the Freemasons in 1784, and remained an active member until his death. His choice to enter the lodge "Zur Wohltätigkeit" was influenced by his friendship with the lodge's master, Baron Otto Heinrich von Gemmingen-Hornberg, and his attraction to the lodge's "shared devotion to Catholic tradition." [10] Nor was Mozart's Masonic commitment the most likely source of his occasional anti-clerical statements, and even less indicative of any essential antipathy to Catholicism. Such anti-clericalism is much more easily attributed to the fashionable anti-clericalism of Febronian Catholicism favored by those in power in Mozart's social ambit at this period, which still reflected curiously a very conservative Counter-Reformation aesthetic environment. [11]

Freemasonry was banned by the Catholic Church in a papal bull entitled In eminenti apostolatus issued by Pope Clement XII on 28 April 1738. The ban, however, "was published and came into force only in the Papal States, Spain, Portugal, and Poland." [12] It was not promulgated in Austria, where Mozart lived, until 1792 (after Mozart's death). Hence, although the Catholic Church's opposition to Freemasonry would eventually become known in Austria, during Mozart's lifetime "a good Catholic could perfectly well become a Mason," and it is clear that Mozart saw no conflict between these two allegiances. [13]

There is conflicting evidence concerning whether Mozart received last rites of the Catholic Church on his death bed. In 1825, 33 years after Mozart's death, Mozart's sister-in-law Sophie Haibel prepared a brief memoir of Mozart's death for her brother-in-law Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, the second husband of Mozart's widow Constanze, who with Constanze's help was then preparing a Mozart biography. Sophie wrote:

My poor sister came after me and begged me for heavens' sake to go to the priests at St Peter's and ask [one of] the priests to come, as if on a chance visit. That I also did, though the priests hesitated a long time and I had great difficulty in persuading one of these inhuman priests to do it. [14]

Further annotations were written on Sophie's letter. One of them, in Nissen's hand, says, "The priests declined to come because the sick person himself did not send for them." [15] According to Halliwell, "A later annotation states that although Mozart did not receive the last rites (presumably absolution and Holy Communion), he was given extreme unction. Thus there is confusion about which, if any, of the sacraments for the sick and dying Mozart received." [16] Gutman claims that Mozart was incapable of receiving any last rites other than extreme unction because he was unconscious at the time. [17] While it is unclear whether Mozart received last rites on his deathbed, there is no evidence suggesting that he actually refused them. Even Nissen, who was of the opinion that the priests failed to come, notes, "Even if Mozart did not receive the last rites, he would have received extreme unction."

Mozart received a Catholic funeral service at St. Stephen's Cathedral and was given exequies at a requiem mass in St. Michael's Church. [18]

During his lifetime, Mozart composed more than 60 pieces of sacred music. The majority were written between 1773 and 1781, when he was employed as court musician to the Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg. [19] Important later liturgical works included the Mass in C minor (K. 427), written for the Salzburg visit of 1783, the motet Ave verum corpus (K. 618), written in Baden in 1791, and the Requiem mass (K. 626), left incomplete at Mozart's death.

Research on paper types by Alan Tyson suggests that a number of works long thought to be Salzburg material actually may date from Mozart's late Vienna years. As Tyson notes, this would make sense since Mozart was at the time engaged in a (successful) campaign to be appointed as the designated successor to Leopold Hofmann in the Kapellmeister position at St. Stephen's Cathedral. [20]

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition resulted in more than 800 works of virtually every genre of his time. Many of these compositions are acknowledged as pinnacles of the symphonic, concertante, chamber, operatic, and choral repertoire. Mozart is widely regarded as among the greatest composers in the history of Western music, with his music admired for its "melodic beauty, its formal elegance and its richness of harmony and texture".

Johann Georg Leopold Mozart was a German composer, violinist, and theorist. He is best known today as the father and teacher of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and for his violin textbook Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule (1756).

The composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart went by many different names in his lifetime. This resulted partly from the church traditions of the day, and partly from Mozart being multilingual and freely adapting his name to other languages.

Georg Nikolaus von Nissen was a Danish diplomat and music historian. He is the author of one of the first biographies of composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, still used today as a scholarly source.

Maria Aloysia Antonia Weber Lange was a German soprano, remembered primarily for her association with the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Maria Anna Walburga Ignatia Mozart, called "Marianne" and nicknamed Nannerl, was a musician, the older sister of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) and daughter of Leopold (1719–1787) and Anna Maria Mozart (1720–1778).

Maria Constanze Cäcilia Josepha Johanna Aloysia Mozart was a trained Austrian singer. She was married twice, first to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart; then to Georg Nikolaus von Nissen. She and Mozart had six children: Karl Thomas Mozart, Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart, and four others who died in infancy. She became Mozart's biographer jointly with her second husband.

The Nannerl Notenbuch, or Notenbuch für Nannerl is a book in which Leopold Mozart, from 1759 to about 1764, wrote pieces for his daughter, Maria Anna Mozart, to learn and play. His son Wolfgang also used the book, in which his earliest compositions were recorded. The book contains simple short keyboard pieces, suitable for beginners; there are many anonymous minuets, some works by Leopold, and a few works by other composers including Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and the Austrian composer Georg Christoph Wagenseil. There are also some technical exercises, a table of intervals, and some modulating figured basses. The notebook originally contained 48 bound pages of music paper, but only 36 pages remain, with some of the missing 12 pages identified in other collections. Because of the simplicity of the pieces it contains, the book is often used to provide instruction to beginning piano players.

The composers Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) and Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) were friends. Their relationship is not very well documented, but the evidence that they enjoyed each other's company is strong. Six string quartets by Mozart are dedicated to Haydn.

On 5 December 1791, the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart died at his home in Vienna, Austria at the age of 35. The circumstances of his death have attracted much research and speculation.

Adolf Heinrich Friedrich Schlichtegroll was a teacher, scholar and the first biographer of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. His brief account of Mozart's life was published in a volume of twelve obituaries Schlichtegroll prepared and called Nekrolog auf das Jahr 1791. The book appeared in 1793, two years after Mozart's death.

Maria Sophie Weber (1763–1846) was a singer of the 18th and 19th centuries. She was the younger sister of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's wife, Constanze, and is remembered primarily for the testimony she left concerning the life and death of her brother-in-law.

Cäcilia Cordula Weber was the mother of Constanze Weber and the mother-in-law of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart died after a short illness on 5 December 1791, aged 35. His reputation as a composer, already strong during his lifetime, rose rapidly in the years after his death, and he became one of the most celebrated of all composers.

Between 1769 and 1773, the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his father Leopold Mozart made three Italian journeys. The first, an extended tour of 15 months, was financed by performances for the nobility and by public concerts, and took in the most important Italian cities. The second and third journeys were to Milan, for Wolfgang to complete operas that had been commissioned there on the first visit. From the perspective of Wolfgang's musical development the journeys were a considerable success, and his talents were recognised by honours which included a papal knighthood and memberships in leading philharmonic societies.

The composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote a great deal of dance music, both for public use and as elements of larger works such as operas, quartets, and symphonies. According to the reminiscences of those who knew him, the composer himself enjoyed dancing very much; he was skillful and danced often.

In 1767, the 11-year-old composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was struck by smallpox. Like all smallpox victims, he was at serious risk of dying, but he survived the disease. This article discusses smallpox as it existed in Mozart's time, the decision taken in 1764 by Mozart's father Leopold not to inoculate his children against the disease, the course of Mozart's illness, and the aftermath.

Bölzlschiessen was a form of domestic recreation that involved shooting darts at decorated targets with an air gun. It is remembered as an activity of Leopold Mozart, his family, and their friends. The most famous participant was Leopold's son Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who began playing at the age of ten or earlier.

The two main labels that have been used to describe the nationality of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart are "Austrian" and "German". However, in Mozart's own life, those terms were used differently from the way they are used today, because the modern nation states of Austria and Germany did not yet exist. Any decision to label Mozart as "Austrian" or "German" involves political boundaries, history, language, culture, and Mozart's own views. Editors of modern encyclopedias and other reference sources differ in how they assign a nationality to Mozart in light of conflicting criteria.

The Missa solemnis in C major, K. 66, is a mass composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1769. It is scored for SATB soloists and choir, violins I and II, viola, 2 oboes, 2 horns, 2 clarini, 2 trumpets and basso continuo.