Triple oppression, also called double jeopardy, Jane Crow, or triple exploitation, is a theory developed by black socialists in the United States, such as Claudia Jones. The theory states that a connection exists between various types of oppression, specifically classism, racism, and sexism. It hypothesizes that all three types of oppression need to be overcome at once.

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a socialist country in Central and Southeast Europe that existed from its foundation in the aftermath of World War II until its dissolution in 1992 amid the Yugoslav Wars. Covering an area of 255,804 km2, the SFRY was bordered by the Adriatic Sea and Italy to the west, Austria and Hungary to the north, Bulgaria and Romania to the east, and Albania and Greece to the south. It was a one-party socialist state and federation governed by the League of Communists of Yugoslavia and made up of six socialist republics—Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia—with Belgrade as its capital; it also included two autonomous provinces within Serbia: Kosovo and Vojvodina.

League of Communists of Croatia was the Croatian branch of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ). It came into power in 1945. Until 1952, it was known as Communist Party of Croatia. In the early 1990s, it underwent several renames and lost power.

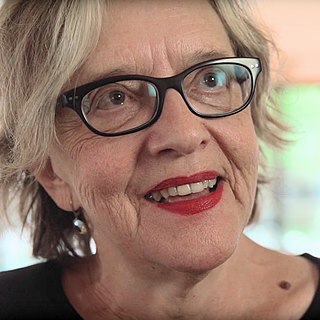

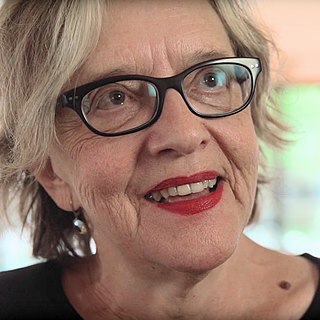

Slavenka Drakulić is a Croatian journalist, novelist, and essayist whose works on feminism, communism, and post-communism have been translated into many languages.

The League of Communists of Yugoslavia, known until 1952 as the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, was the founding and ruling party of SFR Yugoslavia. It was formed in 1919 as the main communist opposition party in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and after its initial successes in the elections, it was proscribed by the royal government and was at times harshly and violently suppressed. It remained an illegal underground group until World War II when, after the invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941, the military arm of the party, the Yugoslav Partisans, became embroiled in a bloody civil war and defeated the Axis powers and their local auxiliaries. After the liberation from foreign occupation in 1945, the party consolidated its power and established a one-party state, which existed until the 1990 breakup of Yugoslavia.

Savka Dabčević-Kučar was a Croatian politician. She was one of the most influential Croatian female politicians during the communist period, especially during the Croatian Spring when she was deposed. She returned to politics during the early days of Croatian independence as the leader of the Coalition of People's Accord and the Croatian People's Party. From 1967 to 1969 she served as the Chairman of the 5th Executive Council of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, one of eight constituent republics and autonomous provinces of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia. She was the first woman in Europe to be appointed head of government of a political entity and the first female in the post-World War II Croatia to hold an office equivalent to a head of government.

They Would Never Hurt a Fly is a 2004 historical non-fiction novel by Slavenka Drakulić discussing the personalities of the war criminals on trial in the Hague that destroyed the former Yugoslavia. Drakulić uses certain trials of alleged criminals with subordinate power to further examine and understand the reasoning behind their misconducts. Most of those discussed are already convicted. In her book, Drakulić does not cover Radovan Karadžić, however, Slobodan Milošević and his wife each rate their own chapter, and Ratko Mladić is portrayed as a Greek tragic figure. There are no pictures, although the physical appearances of the characters are continuously mentioned.

Milka Planinc was a Croatian politician active in SFR Yugoslavia. She served as Prime Minister of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1982 to 1986, the first and only woman to hold this office. Planinc was the first female head of government of a diplomatically recognized Communist state in Europe.

Ljubo Sirc CBE was a British-Slovene economist and prominent dissident from Yugoslavia.

The Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, commonly referred to as Socialist Bosnia or simply Bosnia, was one of the six constituent federal states forming the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It was a predecessor of the modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, existing between 1945 and 1992, under a number of different formal names, including Democratic Bosnia and Herzegovina (1943–1946) and People's Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1946–1963).

Rada Iveković is a Croatian professor, philosopher, Indologist, and writer.

Café Europa: Life After Communism is a 1996 book by Slavenka Drakulić, the noted Croatian writer. It talks about the experiences of the peoples of Eastern Europe after the retreat of socialism and the fall of the Iron Curtain. While Drakulić notes the liberation of the formerly oppressed, her hard hitting social commentary points out the repercussions and lack of progress since the end of Soviet domination.

Slobodan Milošević was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician who served as the president of Serbia within Yugoslavia from 1989 to 1997 and president of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1997 to 2000. Formerly a high-ranking member of the League of Communists of Serbia (SKS) during the 1980s, he led the Socialist Party of Serbia from its foundation in 1990 until 2003.

In Yugoslavia, elections were held while it had existed as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the first one being in 1918 for the Provisional Popular Legislature of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and the last being the parliamentary election of 1938. Women were not eligible to vote. After the 1918 indirect ones, the 1920 parliamentary election was the first direct one. Parliamentary elections were held in 1923, 1925 and 1927, while with the new constitution a de facto Lower and Upper House were introduced in 1931. The 1931 elections were not free, as they were handled under a single-course dictatorship, while the 1935 and 1938 were held under limited basic democratic principles.

Josip Vrhovec was a Croatian communist politician, best known for serving as Yugoslav Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1978 and 1982 and the Chairman of the League of Communists of Croatia from July 1982 to May 1984.

Kristen Rogheh Ghodsee is an American ethnographer and Professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. She is primarily known for her ethnographic work on post-Communist Bulgaria as well as being a contributor to the field of postsocialist gender studies.

The Women's Antifascist Front, was a Yugoslav feminist and anti-fascist mass organisation. The predecessor to several feminist front groups in the former Yugoslavia, and present-day organisations in the region, the AFŽ was heavily involved in organising and participating in the Partisans, the communist and multi-ethnic resistance to Nazi occupation of Yugoslavia during World War II.

The Communist Party of Yugoslavia held its sixth congress in Zagreb on 2–7 November 1952. It was attended by 2,022 delegates representing 779,382 party members. The sixth congress sought to discuss new policies, first of all in reaction to the Yugoslav–Soviet split and Yugoslav rapprochement with the United States. The congress is considered the peak of liberalisation of Yugoslav political life in the 1950s. The congress also renamed the party the League of Communists of Yugoslavia.

Changes in gender roles in Central and Eastern Europe after the fall of Communism have been an object of historical and sociological study.

The Socialist Republic of Croatia, one of the constituent countries of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia had gone through a number of phases in its political life, during which its major political characteristics changed - its name, its top level leadership and ultimately its political organization.