This article needs additional citations for verification .(February 2020) |

The writing systems of the Formosan languages are Latin-based alphabets. Currently, 16 languages (45 dialects) have been regulated. The alphabet was made official in 2005. [1]

This article needs additional citations for verification .(February 2020) |

The writing systems of the Formosan languages are Latin-based alphabets. Currently, 16 languages (45 dialects) have been regulated. The alphabet was made official in 2005. [1]

The Sinckan Manuscripts are one of the earliest written materials of several Formosan languages, including Siraya. This writing system was developed by Dutch missionaries in the period of Dutch rule (1624–1662).

After 1947, with the need for translation of Bible, Latin scripts for Bunun, Paiwan, Taroko, Atayal, and Amis were created. [2] Currently, all 16 Formosan languages are written with similar systems. The Pe̍h-ōe-jī of Taiwanese Hokkien [3] and Pha̍k-fa-sṳ of Taiwanese Hakka were also created with by the western missionaries.

In 2005, standardized writing systems for the languages of Taiwan's 16 recognized indigenous peoples were established by the government. [1]

The table shows how the letters and symbols are used to denote sounds in the 16 officially recognized Formosan languages. [1]

| a | ae | b | c | d | dh | dj | dr | e | é | f | g | h | hl | i | ɨ | j | k | l | lh | lj | lr | m | n | ng | o | oe | p | q | R | r | ṟ | S | s | sh | t | th | tj | tr | u | ʉ | v | w | x | y | z | ' | ^ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amis | a | t͡s | d, ð, ɬ | e | b, f, v | ħ | i | k | ɾ | m | n | ŋ | o | p | r | s | t | u | w | x | j | ʡ | ʔ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atayal | a | β, v | t͡s | e | ɣ | h | i | k | l | m | n | ŋ | o | p | q | r | ɾ | s | t | u | w | x | j | z | ʔ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bunun | a | b | t͡s, t͡ɕ | d | e, ə | x, χ | i | k | l, ɬ | m | n | ŋ | o | p | q | s | t | u | v | ð | ʔ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanakanavu | a | t͡s | e | i | k | m | n | ŋ | o | p | ɾ | s | t | u | ɨ | v | ʔ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kavalan | a | b | ɮ | ə | h | i | k | ɾ | m | n | ŋ | o | p | q | ʁ | s | t | u | w | j | z | ʔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Paiwan | a | b | t͡s | d | ɟ | ɖ | e | g | h | i | k | ɭ | ʎ | m | n | ŋ | p | q | r | s | t | c | u | v | w | j | z | ʔ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Puyuma | a | b | t͡s | d | ɖ | ə | g | h | i | k | ɭ | ɮ | m | n | ŋ | p | r | s | t | ʈ | u | v | w | j | z | ʔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rukai | a | b | t͡s | d | ð | ɖ | ə | e | g | h | i | ɨ | k | l | ɭ | m | n | ŋ | o | p | r | s | t | θ | ʈ | u | v | w | j | z | ʔ | |||||||||||||||||

| Saaroa | a | t͡s | ɬ | i | k | ɾ | m | n | ŋ | p | r | s | t | u | ɨ | v | ʔ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saisiyat | a | æ | β | ə | h | i | k | l | m | n | ŋ | o | œ | p | r | ʃ | s, θ | t | w | j | z, ð | ʔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sakizaya | a | b | t͡s | d, ð, ɬ | ə | ħ | i | k | ɾ | m | n | ŋ | o | p | s | t | u | w | j | z | ʡ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seediq | a | b | t͡s | d | e, ə | g | ħ | i | ɟ | k | l | m | n | ŋ | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | w | x | j | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taroko | a | b | t͡ɕ | d | ə | ɣ | ħ | i | ɟ | k | ɮ | m | n | ŋ | o | p | q | ɾ | s | t | u | w | x | j | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thao | a | b | d | ɸ | h | i | k | l | ɬ | m | n | ŋ | p | q | r | s | ʃ | t | θ | u | β, w | j | ð | ʔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tsou | a | ɓ | t͡s | e | f | x | i | k | ɗ | m | n | ŋ | o | p | s | t | u | v | ɨ | j | z | ʔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yami | a | b | t͡s, t͡ɕ | ɖ | ə | g | ɰ | i | d͡ʒ, d͡ʝ | k | l | m | n | ŋ | o, u | p | ɻ | ʂ | t | f | w | j | r | ʔ |

| | This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2020) |

Revision of the alphabets is under discussion. The table below is a summary of the proposals and decisions (made by the indigenous peoples and linguists). [4] [5] [6] Symbols enclosed with angle brackets ‹› are letters, while those enclosed with square brackets [] are from the International Phonetic Alphabet. The names of dialects are written in Chinese.

| Language | Proposal | 2017 Decision [5] | Final Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amis | 1. Amis, Sakizaya use ‹^› for glottal stop [ʔ] and ‹’› for epiglottal stop [ʡ], while other languages use ‹’› for glottal stop 2. ‹u› and ‹o› seem to be allophones 3. 馬蘭: add ‹i’› for [ε] 4. 南勢: change ‹f› to ‹b› | 1. Continue to use the standard 2. Advised to use only ‹u› or ‹o› 3. Rejected 4. Accepted | |

| Atayal | 1. 賽考利克, 四季: add ‹f›; 萬大: add ‹z› 2. The use of ‹_› to: (1) separate ‹n› and ‹g› sequence from ‹ng›, (2) represent reduced vowel 3. 萬大, 宜蘭澤敖利: delete ‹q› | 1. Rejected 2. Continue to use the standard 3. Accepted | |

| Paiwan | 1. 中排, 南排: use ‹gr› in place of ‹dr› 2. Inconsistent use of ‹w› and ‹v› | 1. To be discussed; 力里 needs a letter for [ɣ] 2. To be discussed | |

| Bunun | 1. Add vowels ‹e› and ‹o› 2. 郡群: ‹ti› changes to ‹ci› (palatalization) 3. 郡群: ‹si› (palatalization) 4. 郡群 uses ‹-› for glottal stop 5. The loss of [ʔ] may cause ‹y› become a phoneme | 1. Accepted 2. To be discussed 3. Remain ‹si› 4. Remain ‹-› | |

| Puyuma | 1. 知本, 初鹿, 建和: add ‹b› 2. 建和: add ‹z› 3. 知本: add ‹dr› 4. 南王: delete ‹’› and ‹h› 5. 知本, 初鹿, 建和, 南王: add ‹o› and ‹ē› 6. The original practice of using ‹l› for retroflex [ɭ] and ‹lr› for [ɮ] (which is [l] in南王) is confusing. It is suggested to use ‹lr› [ɭ], ‹lh› [ɮ], ‹l› [l] | 1. Only in loanwords 2. Only in loanwords 3. Advised not to add 4. Delete ‹h› 5. Only in loanwords 6. Can’t reach agreement 7. Delete ‹’› and use ‹q› for [ʔ] and [ɦ] | |

| Rukai | 1. 大武: add ‹tr› 2. 萬山: add ‹b› and ‹g› 3. 霧台: add ‹é› 4. 多納: Use ‹u› in place of ‹o› | 1. Only in loanwords 2. Only in loanwords 3. Only in loanwords 4. Accepted | |

| Saisiyat | 1. Long vowel sign ‹:› 2. Add ‹c, f, g› | 1. Delete 2. To be discussed | |

| Tsou | 1. Delete ‹r› for [ɽ] 2. Use ‹x› for vowel ‹ʉ› for convenience 3. Add ‹g› 4. ‹l› has two sounds: [ɗ] and [l] | 1. Reserve the letter for 久美 2. Accepted 3. Only in loanwords 4. To be studied | |

| Yami | 1. Churches use ‹h› for both [ʔ] and [ɰ] | 1. ‹’› should be used for [ʔ] | |

| Thao | 1. ‹.› should be used to distinguish ‹lh› (vs. ‹l.h›) and ‹th› (vs. ‹t.h›) | 1. Continue to use the standard 2. Add ‹aa, ii, uu› | |

| Kavalan | 1. The confusion of ‹o› and ‹u› 2. Add trill ‹r› for 樟原 | 1. Add ‹o› to distinguish from ‹u› 2. People from the tribe decided not to add 3. Add ‹y, w› | |

| Taroko | 1. Add ‹’› 2. Add ‹aw, ay, uy, ow, ey› 3. Reduced vowel ‹e› should not be omitted | 1. To be discussed 2. Add ‹ey› [e] 3. People from the tribe wish not to change the current spelling rules | |

| Seediq | 1. 都達、德路固: add ‹aw, ay, uy, ow, ey› 2. Add ‹j› 3. ‹w› should not be omitted 4. Reduced vowel ‹e› should not be omitted | 1. Add ‹ey› [e]; ‹aw, ay, uy› added only in loanwords 2. Only in loanwords 3. People from the tribe wish not to change the current spelling rules 4. People from the tribe wish not to change the current spelling rules | |

| Sakizaya | 1. Delete ‹^› for epiglottal stop 2. Loss of distinction between ‹x› and ‹h› 3. ‹l›, ‹r› seem to be allophones | 1. Accepted; use ‹’› for [ʔ] and [ʡ] 2. Delete ‹x› and keep ‹h› 3. To be discussed 4. Use ‹b› [b] in place of ‹f› | |

| Hla’alua | 1. Add ‹ʉ› for [ɨ] 2. Delete central vowel ‹e› [ə] | 1. Accepted 2. Accepted 3. Remain ‹r› for [r] and ‹l› for [ɾ] | |

| Kanakanavu | 1. Change ‹e› [ə] to ‹e› [e] 2. Add ‹ʉ› for [ɨ] 3. Delete ‹l› | 1. Accepted 2. Accepted 3. Delete ‹l› and use ‹r› for [r, ɾ] |

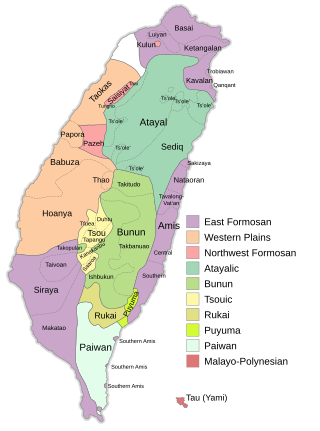

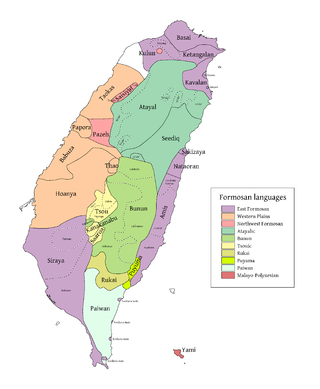

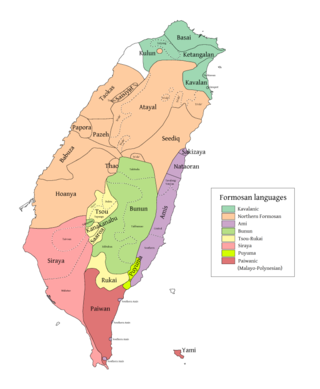

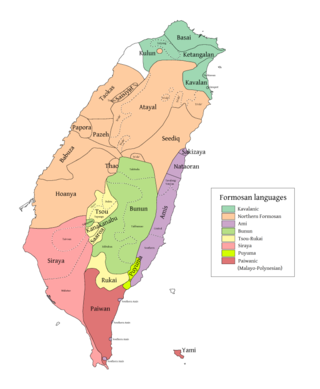

The Formosan languages are a geographic grouping comprising the languages of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, all of which are Austronesian. They do not form a single subfamily of Austronesian but rather up to nine separate primary subfamilies. The Taiwanese indigenous peoples recognized by the government are about 2.3% of the island's population. However, only 35% speak their ancestral language, due to centuries of language shift. Of the approximately 26 languages of the Taiwanese indigenous peoples, at least ten are extinct, another four are moribund, and all others are to some degree endangered.

Paiwan is a native language of Taiwan, spoken by the Paiwan, a Taiwanese indigenous people. Paiwan is a Formosan language of the Austronesian language family. It is also one of the national languages of Taiwan.

The Sinkang Manuscripts are a series of leases, mortgages, and other commerce contracts written in the Sinckan, Taivoan, and Makatao languages. Among Han Chinese, they are commonly referred to as the "barbarian contracts". Some are written only in a Latin-based script, considered the first script to be developed in Taiwan itself, while others were bilingual with adjacent Han writing. Currently there are approximately 140 extant documents written in Sinckan; they are important in the study of Siraya and Taivoan culture, and Taiwanese history in general although there are only a few scholars who can understand them.

Seediq, also known as Sediq, Taroko, is an Atayalic language spoken in the mountains of Northern Taiwan by the Seediq and Taroko people.

Saisiyat is the language of the Saisiyat, a Taiwanese indigenous people. It is a Formosan language of the Austronesian family. It has approximately 4,750 speakers.

Kavalan was formerly spoken in the Northeast coast area of Taiwan by the Kavalan people (噶瑪蘭). It is an East Formosan language of the Austronesian family.

Kanakanavu is a Southern Tsouic language spoken by the Kanakanavu people, an indigenous people of Taiwan. It is a Formosan language of the Austronesian family.

The Seediq are a Taiwanese indigenous people who live primarily in Nantou County and Hualien County. Their language is also known as Seediq.

Tatsuo Nishida was a professor at Kyoto University. His work encompasses research on a variety of Tibeto-Burman languages, he made great contributions in particular to the deciphering of the Tangut language.

The Mak language is a Kam–Sui language spoken in Libo County, Qiannan Prefecture, Guizhou, China. It is spoken mainly in the four townships of Yangfeng, Fangcun (方村), Jialiang (甲良), and Diwo (地莪) in Jialiang District (甲良), Libo County. Mak speakers can also be found in Dushan County. Mak is spoken alongside Ai-Cham and Bouyei. The Mak, also called Mojia (莫家) in Chinese, are officially classified as Bouyei by the Chinese government.

The Bolyu language is an Austroasiatic language of the Pakanic branch.

Sakizaya is a Formosan language closely related to Amis. One of the large family of Austronesian languages, it is spoken by the Sakizaya people, who are concentrated on the eastern Pacific coast of Taiwan. Since 2007 they have been recognized by the Taiwan government as one of the sixteen distinct indigenous groups on the island.

Hagei (Hakei) or Green Gelao is a Gelao language spoken in China and Vietnam.

Yami language, also known as Tao language, is a Malayo-Polynesian and Philippine language spoken by the Tao people of Orchid Island, 46 kilometers southeast of Taiwan. It is a member of the Ivatan dialect continuum.

The Taiwan bamboo partridge is a species of bird in the family Phasianidae. It is endemic to Taiwan. It was formerly considered a subspecies of the Chinese bamboo partridge.

She or Shehua is an unclassified Sinitic language spoken by the She people of Southeastern China. It is also called Shanha, San-hak (山哈) or Shanhahua (山哈话). She speakers are located mainly in Fujian and Zhejiang provinces of Southeastern China, with smaller numbers of speakers in a few locations of Jiangxi, Guangdong and Anhui provinces.

Indigenous Areas are the administrative divisions in Taiwan with significant populations of Taiwanese indigenous peoples. These areas are granted higher level of local autonomy. Currently there are 55 such divisions.

Kolas Yotaka is an Amis Taiwanese politician and journalist. From 2020 to 2022 and again in 2023, she served as spokesperson for the Office of the President under Tsai Ing-wen. Kolas previously served as spokesperson for the Executive Yuan in 2018, the first Taiwanese aboriginal to hold the position.

The Ili Turks are a Turkic ethnic group native to Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture of northern Xinjiang, China. They speak the Ili Turki language, which belongs to the Karluk branch of the Turkic languages. The oral history of the Ili Turks says that they came from the Ferghana Valley of Uzbekistan. The Chinese government does not recognize the Ili Turks as a distinct ethnic group and counts them as Uzbeks in censuses.

NDHU College of Indigenous Studies is a school of Indigenous Studies at National Dong Hwa University (NDHU). Founded in 2001, it traces its root back to the Graduate Institute of Ethnic Relations and Cultures in 1995 with Professor Chiao Chien, the Professor of Anthropology at Indiana University Bloomington and Founding Chair of Anthropology at Chinese University of Hong Kong, as Founding Director.