Classification

The Taivoan language used to be regarded as a dialect of Siraya. However, more evidences have shown that it belongs to an independent language spoken by the Taivoan people.

Documentary evidence

In "De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia" written by the Dutch colonizers during 1629–1662, it was clearly said that when the Dutch people would like to speak to the chieftain of Cannacannavo (Kanakanavu), they needed to translate from Dutch to Sinckan (Siraya), from Sinckan to Tarroequan (possibly a Paiwan or a Rukai language), from Tarroequan to Taivoan, and from Taivoan to Cannacannavo. [4] [5]

"...... in Cannacannavo: Aloelavaos tot welcken de vertolckinge in Sinccans, Tarrocquans en Tevorangs geschiede, weder voor een jaer aengenomen" — "De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia", pp.6–8

Linguistic evidence

A comparison of numerals of Siraya, Taivoan (Tevorangh dialect), and Makatao (Kanapo dialect) with Proto-Austronesian language show the difference among the three Austronesian languages in southwestern Taiwan in the early 20th century: [6] [7]

| PAn | Proto-Siraya | Siraya | Mattauw | Taivoan | Makatao |

|---|

| UM [note 1] | Gospel [note 2] | Kongana [note 3] | Tevorangh [note 4] | Siaurie [note 5] | Eastern [note 6] | Kanapo [note 7] | Bankim

|

|---|

| 1 | *asa | *saat | sa-sat | saat | sasaat | isa | caha' | sa'a | caca'a | na-saad | saat |

| 2 | *duSa | *ðusa | sa-soa | ruha | duha | rusa | ruha | zua | raruha | ra-ruha | laluha |

| 3 | *telu | *turu | tu-turo | turo | turu | tao | toho | too | tatoo | ra-ruma | taturu |

| 4 | *Sepat | *səpat | pa-xpat | xpat | tapat | usipat | paha' | sipat, gasipat | tapat | ra-sipat | hapat |

| 5 | *lima | *rǐma | ri-rima | rima | tu-rima | hima | hima | rima, urima | tarima | ra-lima | lalima |

| 6 | *enem | *nəm | ni-nam | nnum | tu-num | lomu | lom | rumu, urumu | tanum | ra-hurum | anum |

| 7 | *pitu | *pitu | pi-pito | pito | pitu | pitu | kito' | pitoo, upitoo | tyausen | ra-pito | papitu |

| 8 | --- *walu | *kuixpa --- | kuxipat --- | kuixpa --- | pipa --- | vao --- | kipa' --- | --- waru, uwaru | rapako | --- ra-haru | tuda |

| 9 | --- *Siwa | *ma-tuda --- | matuda --- | matuda --- | kuda --- | siva --- | matuha --- | --- hsiya | ravasen | --- ra-siwa | --- |

| 10 | --- | *-ki tian | keteang | kitian | keteng | masu | kaipien | --- | kaiten | ra-kaitian | saatitin |

In 2009, Li (2009) further proved the relationship among the three languages, based on the latest linguistic observations below:

| PAn | Siraya | Taivoan | Makatao |

|---|

| Sound change (1) | *l | r | Ø~h | r |

|---|

| Sound change (2) | *N | l | l | n |

|---|

| Sound change (3) | *D, *d | s | r, d | r, d |

|---|

| Sound change (4) | *k

*S | -k-

-g- | Ø

Ø | -k-

---- |

|---|

Morphological change

(suffices for future tense) | | -ali | -ah | -ani |

|---|

Some examples include: [6] [8]

| PAn | Siraya | Taivoan | Makatao | |

|---|

| Sound change (1) | *telu | turu | toho | toru | three |

| *lima | rima | hima | rima | five, hand |

| *zalan | darang | la'an | raran | road |

| *Caŋila | tangira | tangiya | tangira | ear |

| *bulaN | vural | buan | buran | moon |

| *luCuŋ | rutong | utung | roton | monkey |

| ruvog | uvok, huvok | ruvok | cooked rice |

| karotkot | kau | akuwan | river |

| mirung | mi'un'un | mirun | to sit |

| meisisang | maiyan | mairang | big |

| mururau | mo'owao, mowaowao | ----- | to sing |

| Sound change (2) | *ma-puNi | mapuli | mapuri | mapuni | white |

| tawil | tawin | tawin | year |

| maliko | maniku | maneku | sleep, lie down |

| maling | manung | bimalong | dream |

| *qaNiCu | litu | anito | ngitu | ghost |

| paila | paila | paina | buy |

| ko | kuri, kuli | koni | I |

| Sound change (3) | *Daya | saya | daya | raya | east |

| *DaNum | salom | rarum | ralum | water |

| *lahud | raus | raur | ragut, alut | west |

| sapal | rapan, hyapan | tikat | leg |

| pusux | purux | ----- | country |

| sa | ra, da | ra, da | and |

| kising | kilin | kilin | spoon |

| hiso | hiro | ----- | if |

| Sound change (4) | *kaka | kaka | aka | aka | elder siblings |

| ligig | li'ih | ni'i | sand |

| matagi-vohak | mata'i-vohak | ----- | to regret |

| akusey | kasay | asey | not have |

| Tarokay | Taroay | Tarawey | (personal name) |

Based on the discovery, Li attempted two classification trees: [2]

1. Tree based on the number of phonological innovations

2. Tree based on the relative chronology of sound changes

Li (2009) considers the second tree (the one containing the Taivoan–Makatao group) to be the somewhat more likely one.

Criticism against Candidius' famous assertion

Taivoan was considered by some scholars as a dialectal subgroup of the Siraya ever since George Candidius included "Tefurang" in the eight Siraya villages which he claimed all had "the same manners, customs and religion, and speak the same language." [9] However, American linguist Raleigh Ferrell reexaminates the Dutch materials and says "it appear that the Tevorangians were a distinct ethnolinguistic group, differing markedly in both language and culture from the Siraya." Ferrell mentions that, given that Candidius asserted that he was well familiar with the eight supposed Siraya villages including Tevorang, it's extremely doubtful that he ever actually visited the latter: "it is almost certain, in any case, that he had not visited Tevorang when he wrote his famous account in 1628. The first Dutch visit to Tevorang appears to have been in January 1636 [...]" [1]

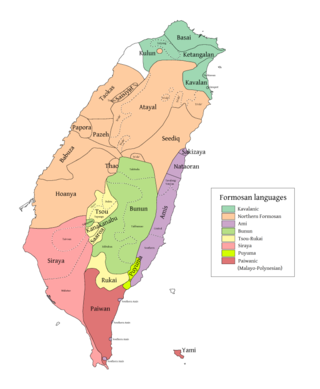

Lee (2015) regards that, when Siraya was a lingua franca among at least eight indigenous communities in southwestern Taiwan plain, Taivoan people from Tevorangh, who has been proved to have their own language in "De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia", might still need the translation service from Wanli, a neighbor community that shared common hunting field and also a militarily alliance with Tevorangh. [5]

Li noted in his "The Lingue Franche in Taiwan" that, Siraya exerted its influence over neighbouring languages in the southwestern plains in Taiwan, including Taivoan to the east and Makatao to the South in the 17th century, and became lingua franca in the whole area. [10]

Phonology

The following is the phonology of the language: [11]

Consonants

It is likely that there were no /g/, /ts/, and /tsʰ/ in the 17th–19th century Taivoan, although Adelaar claims c preceding i or y be sibilant or affricate [12] and so could be /ts/ or /ʃ/. However, the three sounds appeared after the 20th century, especially in Tevorangh dialect in Siaolin, Alikuan, and Dazhuang, and also in some words in Vogavon dialect in Lakku, for example: [13] [14]

- /g/: agang /a'gaŋ (crab), ahagang /aha'gaŋ/ or agaga' /aga'ga?/ (red), gupi /gu'pi/ (Jasminum nervosum Lour.), Anag /a'nag/ (the Taivoan Highest Ancestral Spirit), kogitanta agisen /kogitan'ta agi'sən/ (the Taivoan ceremonial tool to worship the Highest Ancestral Spirits), magun /ma'gun/ (cold), and agicin /agit͡sin/ or agisen /agisən/ (bamboo fishing trap).

- /t͡s/: icikang /it͡si'kaŋ/ (fish), vawciw /vaw't͡siw/ (Hibiscus taiwanensis Hu), cawla /t͡saw'la/ (Lysimachia capillipes Hemsl.), ciwla /t͡siw'la/ (Clausena excavata Burm. f.), and agicin /agit͡sin/ (bamboo fishing trap). The sound also clearly appears in a recording of the typical Taivoan ceremonial song "Kalawahe" sung by Taivoan in Lakku that belongs to Vogavon dialect. [15]

The digraph ts recorded in the early 20th century may represent /t͡sʰ/ or /t͡s/:

- /t͡sʰ/ or /t͡s/: matsa (door, gate), tabutsuk (spear), tsakitsak (arrow), matsihaha (to laugh), tsukun (elbow), atsipi (a sole of the foot), tsau (dog). Only one word is attested in Vogavon dialect in Lakku: katsui (pants, trousers). [6]

Some scholars in Formosan languages suggest it is not likely that /t͡sʰ/ and /t͡s/ appear in a Formosan language simultaneously, and therefore ts may well represent /t͡s/ as c does, not /t͡sʰ/.

Stress

It is hard to tell the actual stressing system of Taivoan in the 17th–19th century, as it has been a dormant language for nearly a hundred years. However, since nearly all the existing Taivoan words but the numerals pronounced by the elders fall on the final syllable, there has been a tendency to stress on the final syllable in modern Taivoan for language revitalization and education, compared to modern Siraya that the penultimate syllable is stressed.

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.