Related Research Articles

Flat Earth is an archaic and scientifically disproven conception of the Earth's shape as a plane or disk. Many ancient cultures subscribed to a flat-Earth cosmography, notably including the cosmology in the ancient Near East. The model has recently undergone a recent resurgence as a conspiracy theory.

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In other words, if the axis of rotation of a body is itself rotating about a second axis, that body is said to be precessing about the second axis. A motion in which the second Euler angle changes is called nutation. In physics, there are two types of precession: torque-free and torque-induced.

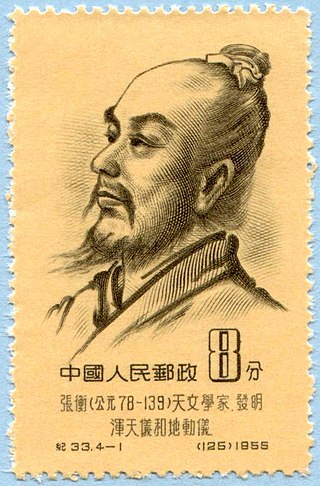

Zhang Heng, formerly romanized Chang Heng, was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman who lived during the Eastern Han dynasty. Educated in the capital cities of Luoyang and Chang'an, he achieved success as an astronomer, mathematician, seismologist, hydraulic engineer, inventor, geographer, cartographer, ethnographer, artist, poet, philosopher, politician, and literary scholar.

The Han dynasty was an imperial dynasty of China established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) and a warring interregnum known as the Chu–Han Contention (206–202 BC), and it was succeeded by the Three Kingdoms period (220–280 AD). The dynasty was briefly interrupted by the Xin dynasty (9–23 AD) established by the usurping regent Wang Mang, and is thus separated into two periods—the Western Han and the Eastern Han (25–220 AD). Spanning over four centuries, the Han dynasty is considered a golden age in Chinese history, and had a permanent impact on Chinese identity in later periods. The majority ethnic group of modern China refer to themselves as the "Han people" or "Han Chinese". The spoken Chinese and written Chinese are referred to respectively as the "Han language" and "Han characters".

In astronomy, axial precession is a gravity-induced, slow, and continuous change in the orientation of an astronomical body's rotational axis. In the absence of precession, the astronomical body's orbit would show axial parallelism. In particular, axial precession can refer to the gradual shift in the orientation of Earth's axis of rotation in a cycle of approximately 26,000 years. This is similar to the precession of a spinning top, with the axis tracing out a pair of cones joined at their apices. The term "precession" typically refers only to this largest part of the motion; other changes in the alignment of Earth's axis—nutation and polar motion—are much smaller in magnitude.

An armillary sphere is a model of objects in the sky, consisting of a spherical framework of rings, centered on Earth or the Sun, that represent lines of celestial longitude and latitude and other astronomically important features, such as the ecliptic. As such, it differs from a celestial globe, which is a smooth sphere whose principal purpose is to map the constellations. It was invented separately, in ancient China possibly as early as the 4th century BC and ancient Greece during the 3rd century BC, with later uses in the Islamic world and Medieval Europe.

Yi Xing, born Zhang Sui, was a Chinese astronomer, Buddhist monk, inventor, mathematician, mechanical engineer, and philosopher during the Tang dynasty. His astronomical celestial globe featured a liquid-driven escapement, the first in a long tradition of Chinese astronomical clockworks.

Shen Kuo or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym MengqiWeng (夢溪翁), was a Chinese polymath, scientist, and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen was a master in many fields of study including mathematics, optics, and horology. In his career as a civil servant, he became a finance minister, governmental state inspector, head official for the Bureau of Astronomy in the Song court, Assistant Minister of Imperial Hospitality, and also served as an academic chancellor. At court his political allegiance was to the Reformist faction known as the New Policies Group, headed by Chancellor Wang Anshi (1021–1085).

Wang Chong, courtesy name Zhongren (仲任), was a Chinese astronomer, meteorologist, naturalist, philosopher, and writer active during the Eastern Han dynasty. He developed a rational, secular, naturalistic and mechanistic account of the world and of human beings and gave a materialistic explanation of the origin of the universe. His main work was the Lunheng. This book contained many theories involving early sciences of astronomy and meteorology, and Wang Chong was even the first in Chinese history to mention the use of the square-pallet chain pump, which became common in irrigation and public works in China thereafter. Wang also accurately described the process of the water cycle.

Astronomy in China has a long history stretching from the Shang dynasty, being refined over a period of more than 3,000 years. The ancient Chinese people have identified stars from 1300 BCE, as Chinese star names later categorized in the twenty-eight mansions have been found on oracle bones unearthed at Anyang, dating back to the mid-Shang dynasty. The core of the "mansion" system also took shape around this period, by the time of King Wu Ding.

Science in the ancient world encompasses the earliest history of science from the protoscience of prehistory and ancient history to late antiquity. In ancient times, culture and knowledge were passed through oral tradition. The development of writing further enabled the preservation of knowledge and culture, allowing information to spread accurately.

Yu Song, courtesy name Shilong, was an official of the Jin dynasty of China. He previously served in the state of Eastern Wu during the Three Kingdoms period. He wrote the Qiong Tian Lun (穹天論), an essay on astronomy.

Jing Fang, born Li Fang (李房), courtesy name Junming (君明), was born in present-day 東郡頓丘 during the Han dynasty. He was a Chinese music theorist, mathematician and astronomer. Although better known for his work in musical measurements, he also accurately described the basic mechanics of lunar and solar eclipses.

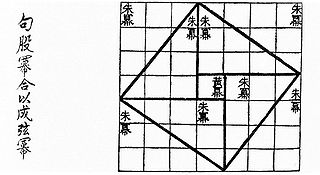

The Zhoubi Suanjing, also known by many other names, is an ancient Chinese astronomical and mathematical work. The Zhoubi is most famous for its presentation of Chinese cosmology and a form of the Pythagorean theorem. It claims to present 246 problems worked out by the Duke of Zhou as well as members of his court, placing its composition during the 11th century BC. However, the present form of the book does not seem to be earlier than the Eastern Han (25–220 AD), with some additions and commentaries continuing to be added for several more centuries.

Ancient Chinese scientists and engineers made significant scientific innovations, findings and technological advances across various scientific disciplines including the natural sciences, engineering, medicine, military technology, mathematics, geology and astronomy.

Li Ye, born Li Zhi, courtesy name Li Jingzhai, was a Chinese mathematician, politician, and writer who published and improved the tian yuan shu method for solving polynomial equations of one variable. Along with the 4th-century Chinese astronomer Yu Xi, Li Ye proposed the idea of a spherical Earth instead of a flat one before the advances of European science in the 17th century.

Fu is an ancient Han Chinese surname of imperial origin which is at least 4,000 years old. The great-great-great-grandson of the Yellow Emperor, Dayou, bestowed this surname to his son Fu Yi and his descendants. Dayou is the eldest son of Danzhu and grandson of Emperor Yao.

Yu is the Mandarin Pinyin spelling of a Chinese given name.

References

- Cullen, Christopher. (1993). "Appendix A: A Chinese Eratosthenes of the Flat Earth: a Study of a Fragment of Cosmology in Huainanzi", in Major, John. S. (ed), Heaven and Earth in Early Han Thought: Chapters Three, Four, and Five of the Huananzi. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1585-6.

- Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping. (2014). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: a Reference Guide, vol 3. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-26788-6.

- Needham, Joseph; Wang, Ling. (1995) [1959]. Science and Civilization in China: Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, vol. 3, reprint edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05801-5.

- Song, Zhenghai; Chen, Chuankang. (1996). "Why did Zheng He’s Sea Voyage Fail to Lead the Chinese to Make the ‘Great Geographic Discovery’?" in Fan, Dainian; Cohen, Robert S. (eds), Chinese Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, translated by Kathleen Dugan and Jiang Mingshan, pp 303-314. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-3463-9.

- Sun, Kwok. (2017). Our Place in the Universe: Understanding Fundamental Astronomy from Ancient Discoveries, second edition. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-54171-6.