The Lassen volcanic area presents a geological record of sedimentation and volcanic activity in and around Lassen Volcanic National Park in Northern California, U.S. The park is located in the southernmost part of the Cascade Mountain Range in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Pacific Oceanic tectonic plates have plunged below the North American Plate in this part of North America for hundreds of millions of years. Heat and molten rock from these subducting plates has fed scores of volcanoes in California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia over at least the past 30 million years, including these in the Lassen volcanic areas.

Mount Mazama is a complex volcano in the western U.S. state of Oregon, in a segment of the Cascade Volcanic Arc and Cascade Range. Most of the mountain collapsed following a major eruption approximately 7,700 years ago. The volcano is in Klamath County, in the southern Cascades, 60 miles (97 km) north of the Oregon–California border. Its collapse, due to the eruption of magma emptying the underlying magma chamber, formed a caldera that holds Crater Lake. Mount Mazama originally had an elevation of 12,000 feet (3,700 m), but following its climactic eruption this was reduced to 8,157 feet (2,486 m). Crater Lake is 1,943 feet (592 m) deep, the deepest freshwater body in the U.S. and the second deepest in North America after Great Slave Lake in Canada.

Mount Garibaldi is a dormant stratovolcano in the Garibaldi Ranges of the Pacific Ranges in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. It has a maximum elevation of 2,678 metres and rises above the surrounding landscape on the east side of the Cheakamus River in New Westminster Land District. In addition to the main peak, Mount Garibaldi has two named sub-peaks. Atwell Peak is a sharp, conical peak slightly higher than the more rounded peak of Dalton Dome. Both were volcanically active at different times throughout Mount Garibaldi's eruptive history. The northern and eastern flanks of Mount Garibaldi are obscured by the Garibaldi Névé, a large snowfield containing several radiating glaciers. Flowing from the steep western face of Mount Garibaldi is the Cheekye River, a tributary of the Cheakamus River. Opal Cone on the southeastern flank is a small volcanic cone from which a lengthy lava flow descends. The western face is a landslide feature that formed in a series of collapses between 12,800 and 11,500 years ago. These collapses resulted in the formation of a large debris flow deposit that fans out into the Squamish Valley.

The Garibaldi Volcanic Belt is a northwest–southeast trending volcanic chain in the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains that extends from Watts Point in the south to the Ha-Iltzuk Icefield in the north. This chain of volcanoes is located in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. It forms the northernmost segment of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, which includes Mount St. Helens and Mount Baker. Most volcanoes of the Garibaldi chain are dormant stratovolcanoes and subglacial volcanoes that have been eroded by glacial ice. Less common volcanic landforms include cinder cones, volcanic plugs, lava domes and calderas. These diverse formations were created by different styles of volcanic activity, including Peléan and Plinian eruptions.

The Chilcotin Group, also called the Chilcotin Plateau Basalts, is a large area of basaltic lava that forms a volcanic plateau running parallel with the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt in south-central British Columbia, Canada.

Hoodoo Mountain, sometimes referred to as Hoodoo Volcano, is a potentially active stratovolcano in the Northern Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It is located 25 kilometres northeast of the Alaska–British Columbia border on the north side of the Iskut River opposite of the mouth of the Craig River. With a summit elevation of 1,850 metres and a topographic prominence of 900 metres, Hoodoo Mountain is one of many prominent peaks within the Boundary Ranges of the Coast Mountains. Its flat-topped summit is covered by an ice cap more than 100 metres thick and at least 3 kilometres in diameter. Two valley glaciers surrounding the northwestern and northeastern sides of the mountain have retreated significantly over the last hundred years. They both originate from a large icefield to the north and are the sources of two meltwater streams. These streams flow along the western and eastern sides of the volcano before draining into the Iskut River.

The Mount Meager massif is a group of volcanic peaks in the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. Part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc of western North America, it is located 150 km (93 mi) north of Vancouver at the northern end of the Pemberton Valley and reaches a maximum elevation of 2,680 m (8,790 ft). The massif is capped by several eroded volcanic edifices, including lava domes, volcanic plugs and overlapping piles of lava flows; these form at least six major summits including Mount Meager which is the second highest of the massif.

Mount Fee is a volcanic peak in the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. It is located 13 km (8.1 mi) south of Callaghan Lake and 21 km (13 mi) west of the resort town of Whistler. With a summit elevation of 2,162 m (7,093 ft) and a topographic prominence of 312 m (1,024 ft), it rises above the surrounding rugged landscape on an alpine mountain ridge. This mountain ridge represents the base of a north-south trending volcanic field which Mount Fee occupies.

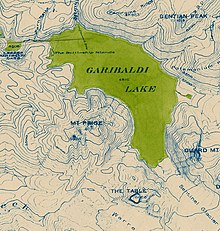

The Garibaldi Lake volcanic field is a volcanic field, located in British Columbia, Canada. It was formed by a group of nine small andesitic stratovolcanoes and basaltic andesite vents in the scenic Garibaldi Lake area immediately north of Mount Garibaldi during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene. The oldest stratovolcano, The Black Tusk, formed between about 1.3 and 1.1 million years ago (Ma). Following glacial dissection, renewed volcanism produced the lava dome and flow forming its summit. Other Pleistocene vents are located along and to the west of the Cheakamus River. Cinder Cone, to the east of The Black Tusk, produced a 9-km-long lava flow during the late Pleistocene or early Holocene.

The Cascade Volcanoes are a number of volcanoes in a volcanic arc in western North America, extending from southwestern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California, a distance of well over 700 miles (1,100 km). The arc formed due to subduction along the Cascadia subduction zone. Although taking its name from the Cascade Range, this term is a geologic grouping rather than a geographic one, and the Cascade Volcanoes extend north into the Coast Mountains, past the Fraser River which is the northward limit of the Cascade Range proper.

Level Mountain is a large volcanic complex in the Northern Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It is located 50 kilometres north-northwest of Telegraph Creek and 60 kilometres west of Dease Lake on the Nahlin Plateau. With a maximum elevation of 2,164 metres, it is the second-highest of four large complexes in an extensive north–south trending volcanic region. Much of the mountain is gently-sloping; when measured from its base, Level Mountain is about 1,100 metres tall, slightly taller than its neighbour to the northwest, Heart Peaks. The lower, broader half of Level Mountain consists of a shield-like structure while its upper half has a more steep, jagged profile. Its broad summit is dominated by the Level Mountain Range, a small mountain range with prominent peaks cut by deep valleys. These valleys serve as a radial drainage for several small streams that flow from the mountain. Meszah Peak is the only named peak in the Level Mountain Range.

Volcanic activity is a major part of the geology of Canada and is characterized by many types of volcanic landform, including lava flows, volcanic plateaus, lava domes, cinder cones, stratovolcanoes, shield volcanoes, submarine volcanoes, calderas, diatremes, and maars, along with less common volcanic forms such as tuyas and subglacial mounds.

The geology of the Pacific Northwest includes the composition, structure, physical properties and the processes that shape the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The region is part of the Ring of Fire: the subduction of the Pacific and Farallon Plates under the North American Plate is responsible for many of the area's scenic features as well as some of its hazards, such as volcanoes, earthquakes, and landslides.

The Barrier is a lava dam retaining the Garibaldi Lake system in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. It is over 300 m (980 ft) thick and about 2.4 km (1.5 mi) long where it impounds the lake.

The Silverthrone Caldera is a potentially active caldera complex in southwestern British Columbia, Canada, located over 350 kilometres (220 mi) northwest of the city of Vancouver and about 50 kilometres (31 mi) west of Mount Waddington in the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains. The caldera is one of the largest of the few calderas in western Canada, measuring about 30 kilometres (19 mi) long (north-south) and 20 kilometres (12 mi) wide (east-west). Mount Silverthrone, an eroded lava dome on the caldera's northern flank that is 2,864 metres (9,396 ft) high, may be the highest volcano in Canada.

The Volcano, also known as Lava Fork volcano, is a small cinder cone in the Boundary Ranges of the Coast Mountains in northwestern British Columbia, Canada. It is located approximately 60 km (40 mi) northwest of the small community of Stewart near the head of Lava Fork. With a summit elevation of 1,656 m (5,433 ft) and a topographic prominence of 311 m (1,020 ft), it rises above the surrounding rugged landscape on a remote mountain ridge that represents the northern flank of a glaciated U-shaped valley.

The volcanic history of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province presents a record of volcanic activity in northwestern British Columbia, central Yukon and the U.S. state of easternmost Alaska. The volcanic activity lies in the northern part of the Western Cordillera of the Pacific Northwest region of North America. Extensional cracking of the North American Plate in this part of North America has existed for millions of years. Continuation of this continental rifting has fed scores of volcanoes throughout the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province over at least the past 20 million years and occasionally continued into geologically recent times.

The Canadian Cascade Arc, also called the Canadian Cascades, is the Canadian segment of the North American Cascade Volcanic Arc. Located entirely within the Canadian province of British Columbia, it extends from the Cascade Mountains in the south to the Coast Mountains in the north. Specifically, the southern end of the Canadian Cascades begin at the Canada–United States border. However, the specific boundaries of the northern end are not precisely known and the geology in this part of the volcanic arc is poorly understood. It is widely accepted by geologists that the Canadian Cascade Arc extends through the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains. However, others have expressed concern that the volcanic arc possibly extends further north into the Kitimat Ranges, another subdivision of the Coast Mountains, and even as far north as Haida Gwaii.

The Mount Cayley volcanic field (MCVF) is a remote volcanic zone on the South Coast of British Columbia, Canada, stretching 31 km (19 mi) from the Pemberton Icefield to the Squamish River. It forms a segment of the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, the Canadian portion of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, which extends from Northern California to southwestern British Columbia. Most of the MCVF volcanoes were formed during periods of volcanism under sheets of glacial ice throughout the last glacial period. These subglacial eruptions formed steep, flat-topped volcanoes and subglacial lava domes, most of which have been entirely exposed by deglaciation. However, at least two volcanoes predate the last glacial period and both are highly eroded. The field gets its name from Mount Cayley, a volcanic peak located at the southern end of the Powder Mountain Icefield. This icefield covers much of the central portion of the volcanic field and is one of the several glacial fields in the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains.

Mount Cayley is an eroded but potentially active stratovolcano in the Pacific Ranges of southwestern British Columbia, Canada. Located 45 km (28 mi) north of Squamish and 24 km (15 mi) west of Whistler, the volcano resides on the edge of the Powder Mountain Icefield. It consists of massif that towers over the Cheakamus and Squamish river valleys. All major summits have elevations greater than 2,000 m (6,600 ft), Mount Cayley being the highest at 2,385 m (7,825 ft). The surrounding area has been inhabited by indigenous peoples for more than 7,000 years while geothermal exploration has taken place there for the last four decades.