Related Research Articles

In neuroscience and psychology, the term language center refers collectively to the areas of the brain which serve a particular function for speech processing and production. Language is a core system that gives humans the capacity to solve difficult problems and provides them with a unique type of social interaction. Language allows individuals to attribute symbols to specific concepts, and utilize them through sentences and phrases that follow proper grammatical rules. Finally, speech is the mechanism by which language is orally expressed.

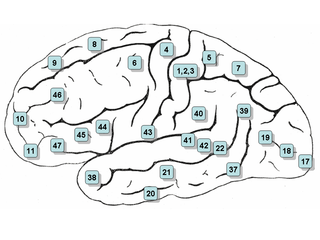

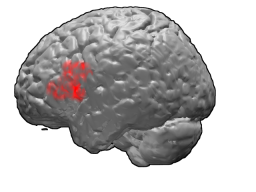

Broca's area, or the Broca area, is a region in the frontal lobe of the dominant hemisphere, usually the left, of the brain with functions linked to speech production.

Psycholinguistics or psychology of language is the study of the interrelation between linguistic factors and psychological aspects. The discipline is mainly concerned with the mechanisms by which language is processed and represented in the mind and brain; that is, the psychological and neurobiological factors that enable humans to acquire, use, comprehend, and produce language.

Neurolinguistics is the study of neural mechanisms in the human brain that control the comprehension, production, and acquisition of language. As an interdisciplinary field, neurolinguistics draws methods and theories from fields such as neuroscience, linguistics, cognitive science, communication disorders and neuropsychology. Researchers are drawn to the field from a variety of backgrounds, bringing along a variety of experimental techniques as well as widely varying theoretical perspectives. Much work in neurolinguistics is informed by models in psycholinguistics and theoretical linguistics, and is focused on investigating how the brain can implement the processes that theoretical and psycholinguistics propose are necessary in producing and comprehending language. Neurolinguists study the physiological mechanisms by which the brain processes information related to language, and evaluate linguistic and psycholinguistic theories, using aphasiology, brain imaging, electrophysiology, and computer modeling.

Generative grammar, or generativism, is a linguistic theory that regards linguistics as the study of a hypothesised innate grammatical structure. It is a biological or biologistic modification of earlier structuralist theories of linguistics, deriving from logical syntax and glossematics. Generative grammar considers grammar as a system of rules that generates exactly those combinations of words that form grammatical sentences in a given language. It is a system of explicit rules that may apply repeatedly to generate an indefinite number of sentences which can be as long as one wants them to be. The difference from structural and functional models is that the object is base-generated within the verb phrase in generative grammar. This purportedly cognitive structure is thought of as being a part of a universal grammar, a syntactic structure which is caused by a genetic mutation in humans.

Brodmann area 45 (BA45), is part of the frontal cortex in the human brain. It is situated on the lateral surface, inferior to BA9 and adjacent to BA46.

An event-related potential (ERP) is the measured brain response that is the direct result of a specific sensory, cognitive, or motor event. More formally, it is any stereotyped electrophysiological response to a stimulus. The study of the brain in this way provides a noninvasive means of evaluating brain functioning.

The N400 is a component of time-locked EEG signals known as event-related potentials (ERP). It is a negative-going deflection that peaks around 400 milliseconds post-stimulus onset, although it can extend from 250-500 ms, and is typically maximal over centro-parietal electrode sites. The N400 is part of the normal brain response to words and other meaningful stimuli, including visual and auditory words, sign language signs, pictures, faces, environmental sounds, and smells.

The mismatch negativity (MMN) or mismatch field (MMF) is a component of the event-related potential (ERP) to an odd stimulus in a sequence of stimuli. It arises from electrical activity in the brain and is studied within the field of cognitive neuroscience and psychology. It can occur in any sensory system, but has most frequently been studied for hearing and for vision, in which case it is abbreviated to vMMN. The (v)MMN occurs after an infrequent change in a repetitive sequence of stimuli For example, a rare deviant (d) stimulus can be interspersed among a series of frequent standard (s) stimuli. In hearing, a deviant sound can differ from the standards in one or more perceptual features such as pitch, duration, loudness, or location. The MMN can be elicited regardless of whether someone is paying attention to the sequence. During auditory sequences, a person can be reading or watching a silent subtitled movie, yet still show a clear MMN. In the case of visual stimuli, the MMN occurs after an infrequent change in a repetitive sequence of images.

Language production is the production of spoken or written language. In psycholinguistics, it describes all of the stages between having a concept to express and translating that concept into linguistic forms. These stages have been described in two types of processing models: the lexical access models and the serial models. Through these models, psycholinguists can look into how speeches are produced in different ways, such as when the speaker is bilingual. Psycholinguists learn more about these models and different kinds of speech by using language production research methods that include collecting speech errors and elicited production tasks.

Sentence processing takes place whenever a reader or listener processes a language utterance, either in isolation or in the context of a conversation or a text. Many studies of the human language comprehension process have focused on reading of single utterances (sentences) without context. Extensive research has shown that language comprehension is affected by context preceding a given utterance as well as many other factors.

The bǎ construction is a grammatical construction in the Chinese language. In a bǎ construction, the object of a verb is placed after the function word 把; bǎ, and the verb placed after the object, forming a subject–object–verb (SOV) sentence. Linguists commonly analyze bǎ as a light verb construction, or as a preposition.

The early left anterior negativity is an event-related potential in electroencephalography (EEG), or component of brain activity that occurs in response to a certain kind of stimulus. It is characterized by a negative-going wave that peaks around 200 milliseconds or less after the onset of a stimulus, and most often occurs in response to linguistic stimuli that violate word-category or phrase structure rules. As such, it is frequently a topic of study in neurolinguistics experiments, specifically in areas such as sentence processing. While it is frequently used in language research, there is no evidence yet that it is necessarily a language-specific phenomenon.

In neuroscience, the lateralized readiness potential (LRP) is an event-related brain potential, or increase in electrical activity at the surface of the brain, that is thought to reflect the preparation of motor activity on a certain side of the body; in other words, it is a spike in the electrical activity of the brain that happens when a person gets ready to move one arm, leg, or foot. It is a special form of bereitschaftspotential. LRPs are recorded using electroencephalography (EEG) and have numerous applications in cognitive neuroscience.

Music semantics refers to the ability of music to convey semantic meaning. Semantics are a key feature of language, and whether music shares some of the same ability to prime and convey meaning has been the subject of recent study.

The N200, or N2, is an event-related potential (ERP) component. An ERP can be monitored using a non-invasive electroencephalography (EEG) cap that is fitted over the scalp on human subjects. An EEG cap allows researchers and clinicians to monitor the minute electrical activity that reaches the surface of the scalp from post-synaptic potentials in neurons, which fluctuate in relation to cognitive processing. EEG provides millisecond-level temporal resolution and is therefore known as one of the most direct measures of covert mental operations in the brain. The N200 in particular is a negative-going wave that peaks 200-350ms post-stimulus and is found primarily over anterior scalp sites. Past research focused on the N200 as a mismatch detector, but it has also been found to reflect executive cognitive control functions, and has recently been used in the study of language.

The late positive component or late positive complex (LPC) is a positive-going event-related brain potential (ERP) component that has been important in studies of explicit recognition memory. It is generally found to be largest over parietal scalp sites, beginning around 400–500 ms after the onset of a stimulus and lasting for a few hundred milliseconds. It is an important part of the ERP "old/new" effect, which may also include modulations of an earlier component similar to an N400. Similar positivities have sometimes been referred to as the P3b, P300, and P600. Here, we use the term "LPC" in reference to this late positive component.

Angela Friederici is a director at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, and is an internationally recognized expert in neuropsychology and linguistics. She is the author of over 400 academic articles and book chapters, and has edited 15 books on linguistics, neuroscience, language and psychology.

Linguistic prediction is a phenomenon in psycholinguistics occurring whenever information about a word or other linguistic unit is activated before that unit is actually encountered. Evidence from eyetracking, event-related potentials, and other experimental methods indicates that in addition to integrating each subsequent word into the context formed by previously encountered words, language users may, under certain conditions, try to predict upcoming words. In particular, prediction seems to occur regularly when the context of a sentence greatly limits the possible words that have not yet been revealed. For instance, a person listening to a sentence like, "In the summer it is hot, and in the winter it is..." would be highly likely to predict the sentence completion "cold" in advance of actually hearing it. A form of prediction is also thought to occur in some types of lexical priming, a phenomenon whereby a word becomes easier to process if it is preceded by a related word. Linguistic prediction is an active area of research in psycholinguistics and cognitive neuroscience.

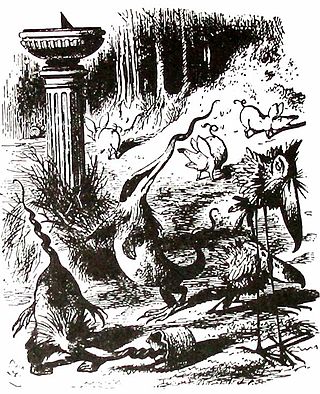

A Jabberwocky sentence is a type of sentence of interest in neurolinguistics. Jabberwocky sentences take their name from the language of Lewis Carroll's well-known poem "Jabberwocky". In the poem, Carroll uses correct English grammar and syntax, but many of the words are made up and merely suggest meaning. A Jabberwocky sentence is therefore a sentence which uses correct grammar and syntax but contains nonsense words, rendering it semantically meaningless.

References

- ↑ Hagoort 2007 , p. 251

- 1 2 Hagoort, Brown & Osterhout 1999 , p. 286

- 1 2 Gouvea et al. 2009 , p. 7

- 1 2 Kaan & Swaab 2003 , p. 98

- ↑ Service et al. 2007 , pp. 1200–1202

- 1 2 3 Coulson, King & Kutas 1998 , p. 26

- ↑ Gouvea et al. 2009 , p. 4

- ↑ Coulson, King & Kutas 1998 , p. 22

- ↑ Friederici & Weissenborn 2007 , p. 51

- ↑ Hagoort, Brown & Osterhout 1999 , pp. 283–84

- ↑ Gouvea et al. 2009 , p. 6

- ↑ Gouvea et al. 2009 , p. 29

- ↑ Gouvea et al. 2009 , p. 8

- ↑ Patel, A.D.; Gibson, E.; Ratner, J.; Besson, M.; Holcomb, P.J.; et al. (1998). "Processing syntactic relations in language and music: An event-related potential study". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 10 (6): 717–33. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.592.6210 . doi:10.1162/089892998563121. PMID 9831740. S2CID 972521.

- ↑ Gouvea et al. 2009 , p. 11

- ↑ Kaan & Swaab 2003 , p. 99

- ↑ beim Graben, Gerth & Vasishth 2008

- ↑ See, for example, and the numerous references therein.

- ↑ Friederici 2002 , p. 79

- ↑ Kaan & Swaab 2003

- ↑ Hagoort 2003

- ↑ Gouvea et al. 2009 , p. 45

- ↑ Coulson, King & Kutas 1998

- ↑ Fitz, Hartmut; Chang, Franklin (2019). "Language ERPs reflect learning through prediction error propagation". Cognitive Psychology. 111: 15–52. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2019.03.002. hdl: 21.11116/0000-0003-474F-6 . PMID 30921626. S2CID 85501792.