Related Research Articles

Obstetrics is the field of study concentrated on pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. As a medical specialty, obstetrics is combined with gynecology under the discipline known as obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN), which is a surgical field.

Miscarriage, also known in medical terms as a spontaneous abortion, is the death and expulsion of an embryo or fetus before it is able to survive independently. The term miscarriage is sometimes used to refer to all forms of pregnancy loss and pregnancy with abortive outcome before 20 weeks of gestation.

Pre-eclampsia is a multi-system disorder specific to pregnancy, characterized by the onset of high blood pressure and often a significant amount of protein in the urine. When it arises, the condition begins after 20 weeks of pregnancy. In severe cases of the disease there may be red blood cell breakdown, a low blood platelet count, impaired liver function, kidney dysfunction, swelling, shortness of breath due to fluid in the lungs, or visual disturbances. Pre-eclampsia increases the risk of undesirable as well as lethal outcomes for both the mother and the fetus including preterm labor. If left untreated, it may result in seizures at which point it is known as eclampsia.

Preterm birth, also known as premature birth, is the birth of a baby at fewer than 37 weeks gestational age, as opposed to full-term delivery at approximately 40 weeks. Extreme preterm is less than 28 weeks, very early preterm birth is between 28 and 32 weeks, early preterm birth occurs between 32 and 34 weeks, late preterm birth is between 34 and 36 weeks' gestation. These babies are also known as premature babies or colloquially preemies or premmies. Symptoms of preterm labor include uterine contractions which occur more often than every ten minutes and/or the leaking of fluid from the vagina before 37 weeks. Premature infants are at greater risk for cerebral palsy, delays in development, hearing problems and problems with their vision. The earlier a baby is born, the greater these risks will be.

Recurrent miscarriage or recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) is the spontaneous loss of 2-3 pregnancies that is estimated to affect up to 5% of women. The exact number of pregnancy losses and gestational weeks used to define RPL differs among medical societies. In the majority of cases, the exact cause of pregnancy loss is unexplained despite genetic testing and a thorough evaluation. When a cause for RPL is identified, almost half are attributed to a chromosomal abnormality. RPL has been associated with several risk factors including parental and genetic factors, congenital and acquired anatomical conditions, lifestyle factors, endocrine disorders, thrombophila, immunological factors, and infections. The American Society of Reproductive Medicine recommends a thorough evaluation after 2 consecutive pregnancy losses, however, this can differ from recommendations by other medical societies. RPL evaluation be evaluated by numerous tests and imaging studies depending on the risk factors. These range from cytogenetic studies, blood tests for clotting disorders, hormone levels, diabetes screening, thyroid function tests, sperm analysis, antibody testing, and imaging studies. Treatment is typically tailored to the relevant risk factors and test findings. RPL can have a significant impact on the psychological well-being of couples and has been associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. Therefore, it is recommended that appropriate screening and management be considered by medical providers.

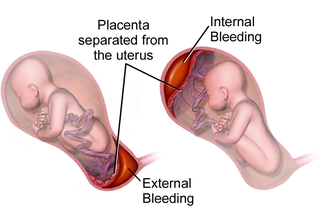

Placental abruption is when the placenta separates early from the uterus, in other words separates before childbirth. It occurs most commonly around 25 weeks of pregnancy. Symptoms may include vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, and dangerously low blood pressure. Complications for the mother can include disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and kidney failure. Complications for the baby can include fetal distress, low birthweight, preterm delivery, and stillbirth.

Bloody show or show is the passage of a small amount of blood or blood-tinged mucus through the vagina near the end of pregnancy. It is caused by thinning and dilation of the cervix, leading to detachment of the cervical mucus plug that seals the cervix during pregnancy and tearing of small cervical blood vessels, and is one of the signs that labor may be imminent. The bloody show may be expelled from the vagina in pieces or altogether and often appears as a jelly-like piece of mucus stained with blood. Although the bloody show may be alarming at first, it is not a concern of patient health after 37 weeks gestation.

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring develops (gestates) inside a woman's uterus (womb). A multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Prenatal development includes the development of the embryo and of the fetus during a viviparous animal's gestation. Prenatal development starts with fertilization, in the germinal stage of embryonic development, and continues in fetal development until birth.

Complications of pregnancy are health problems that are related to, or arise during pregnancy. Complications that occur primarily during childbirth are termed obstetric labor complications, and problems that occur primarily after childbirth are termed puerperal disorders. While some complications improve or are fully resolved after pregnancy, some may lead to lasting effects, morbidity, or in the most severe cases, maternal or fetal mortality.

Nutrition and pregnancy refers to the nutrient intake, and dietary planning that is undertaken before, during and after pregnancy. Nutrition of the fetus begins at conception. For this reason, the nutrition of the mother is important from before conception as well as throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding. An ever-increasing number of studies have shown that the nutrition of the mother will have an effect on the child, up to and including the risk for cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes throughout life.

Maternal health is the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. In most cases, maternal health encompasses the health care dimensions of family planning, preconception, prenatal, and postnatal care in order to ensure a positive and fulfilling experience. In other cases, maternal health can reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. Maternal health revolves around the health and wellness of pregnant women, particularly when they are pregnant, at the time they give birth, and during child-raising. WHO has indicated that even though motherhood has been considered as a fulfilling natural experience that is emotional to the mother, a high percentage of women develop health problems and sometimes even die. Because of this, there is a need to invest in the health of women. The investment can be achieved in different ways, among the main ones being subsidizing the healthcare cost, education on maternal health, encouraging effective family planning, and ensuring progressive check up on the health of women with children. Maternal morbidity and mortality particularly affects women of color and women living in low and lower-middle income countries.

Maternal–fetal medicine (MFM), also known as perinatology, is a branch of medicine that focuses on managing health concerns of the mother and fetus prior to, during, and shortly after pregnancy.

Tobacco smoking during pregnancy causes many detrimental effects on health and reproduction, in addition to the general health effects of tobacco. A number of studies have shown that tobacco use is a significant factor in miscarriages among pregnant smokers, and that it contributes to a number of other threats to the health of the foetus.

Thyroid disease in pregnancy can affect the health of the mother as well as the child before and after delivery. Thyroid disorders are prevalent in women of child-bearing age and for this reason commonly present as a pre-existing disease in pregnancy, or after childbirth. Uncorrected thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy has adverse effects on fetal and maternal well-being. The deleterious effects of thyroid dysfunction can also extend beyond pregnancy and delivery to affect neurointellectual development in the early life of the child. Due to an increase in thyroxine binding globulin, an increase in placental type 3 deioidinase and the placental transfer of maternal thyroxine to the fetus, the demand for thyroid hormones is increased during pregnancy. The necessary increase in thyroid hormone production is facilitated by high human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) concentrations, which bind the TSH receptor and stimulate the maternal thyroid to increase maternal thyroid hormone concentrations by roughly 50%. If the necessary increase in thyroid function cannot be met, this may cause a previously unnoticed (mild) thyroid disorder to worsen and become evident as gestational thyroid disease. Currently, there is not enough evidence to suggest that screening for thyroid dysfunction is beneficial, especially since treatment thyroid hormone supplementation may come with a risk of overtreatment. After women give birth, about 5% develop postpartum thyroiditis which can occur up to nine months afterwards. This is characterized by a short period of hyperthyroidism followed by a period of hypothyroidism; 20–40% remain permanently hypothyroid.

A high-risk pregnancy is one where the mother or the fetus has an increased risk of adverse outcomes compared to uncomplicated pregnancies. No concrete guidelines currently exist for distinguishing “high-risk” pregnancies from “low-risk” pregnancies; however, there are certain studied conditions that have been shown to put the mother or fetus at a higher risk of poor outcomes. These conditions can be classified into three main categories: health problems in the mother that occur before she becomes pregnant, health problems in the mother that occur during pregnancy, and certain health conditions with the fetus.

Obstetric medicine, similar to maternal medicine, is a sub-specialty of general internal medicine and obstetrics that specializes in process of prevention, diagnosing, and treating medical disorders in with pregnant women. It is closely related to the specialty of maternal-fetal medicine, although obstetric medicine does not directly care for the fetus. The practice of obstetric medicine, or previously known as "obstetric intervention," primarily consisted of the extraction of the baby during instances of duress, such as obstructed labor or if the baby was positioned in breech.

Hypertensive disease of pregnancy, also known as maternal hypertensive disorder, is a group of high blood pressure disorders that include preeclampsia, preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, and chronic hypertension.

Fetal programming, also known as prenatal programming, is the theory that environmental cues experienced during fetal development play a seminal role in determining health trajectories across the lifespan.

Maternal health outcomes differ significantly between racial groups within the United States. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists describes these disparities in obstetric outcomes as "prevalent and persistent." Black, indigenous, and people of color are disproportionately affected by many of the maternal health outcomes listed as national objectives in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services's national health objectives program, Healthy People 2030. The American Public Health Association considers maternal mortality to be a human rights issue, also noting the disparate rates of Black maternal death. Race affects maternal health throughout the pregnancy continuum, beginning prior to conception and continuing through pregnancy (antepartum), during labor and childbirth (intrapartum), and after birth (postpartum).

References

- ↑ Bramham, Kate; Parnell, Bethany; Nelson-Piercy, Catherine; Seed, Paul T; Poston, Lucilla; Chappell, Lucy C (2014-04-15). "Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis". The BMJ. 348: g2301. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2301. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 3988319 . PMID 24735917.

- ↑ Al Khalaf, Sukainah Y.; O'Reilly, Éilis J.; Barrett, Peter M.; B. Leite, Debora F.; Pawley, Lauren C.; McCarthy, Fergus P.; Khashan, Ali S. (2021-05-04). "Impact of Chronic Hypertension and Antihypertensive Treatment on Adverse Perinatal Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis". Journal of the American Heart Association. 10 (9). doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.018494. ISSN 2047-9980. PMC 8200761 . PMID 33870708.

- ↑ "Pregnancy complications increase the risk of heart attacks and stroke in women with high blood pressure". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2023-11-21. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_60660.

- ↑ Al Khalaf, Sukainah; Chappell, Lucy C.; Khashan, Ali S.; McCarthy, Fergus P.; O’Reilly, Éilis J. (12 May 2023). "Association Between Chronic Hypertension and the Risk of 12 Cardiovascular Diseases Among Parous Women: The Role of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes". Hypertension. 80 (7): 1427–1438. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.20628 . ISSN 0194-911X.

- ↑ Webster, Louise M.; Conti‐Ramsden, Frances; Seed, Paul T.; Webb, Andrew J.; Nelson‐Piercy, Catherine; Chappell, Lucy C. (2017-05-17). "Impact of Antihypertensive Treatment on Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes in Pregnancy Complicated by Chronic Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of the American Heart Association: Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Disease. 6 (5). doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.005526. ISSN 2047-9980. PMC 5524099 . PMID 28515115.

- 1 2 3 Spencer, L; Bubner, T; Bain, E; Middleton, P (21 September 2015). "Screening and subsequent management for thyroid dysfunction pre-pregnancy and during pregnancy for improving maternal and infant health". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (9): CD011263. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011263.pub2. PMC 9233937 . PMID 26387772.

- 1 2 Page 264 in: Gresele, Paolo (2008). Platelets in hematologic and cardiovascular disorders: a clinical handbook. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88115-9.

- ↑ K E Ugen; J J Goedert; J Boyer; Y Refaeli; I Frank; W V Williams; A Willoughby; S Landesman; H Mendez; A Rubinstein (June 1992). "Vertical transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Reactivity of maternal sera with glycoprotein 120 and 41 peptides from HIV type 1". J Clin Invest. 89 (6): 1923–1930. doi:10.1172/JCI115798. PMC 295892 . PMID 1601999.

- ↑ Fawzi WW, Msamanga G, Hunter D, Urassa E, Renjifo B, Mwakagile D, Hertzmark E, Coley J, Garland M, Kapiga S, Antelman G, Essex M, Spiegelman D (1999). "Randomized trial of vitamin supplements in relation to vertical transmission of HIV-1 in Tanzania". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 23 (3): 246–254. doi:10.1097/00042560-200003010-00006. PMID 10839660. S2CID 35936352.

- ↑ Lee MJ, Hallmark RJ, Frenkel LM, Del Priore G (1998). "Maternal syphilis and vertical perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 63 (3): 246–254. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(98)00165-9. PMID 9989893. S2CID 22297001.

- 1 2 Health Care Guideline: Routine Prenatal Care. Fourteenth Edition. Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine By the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. July 2010.

- ↑ Sobel, JD (9 June 2007). "Vulvovaginal candidosis". Lancet. 369 (9577): 1961–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60917-9. PMID 17560449. S2CID 33894309.

- ↑ Roberts, C. L.; Rickard, K.; Kotsiou, G.; Morris, J. M. (2011). "Treatment of asymptomatic vaginal candidiasis in pregnancy to prevent preterm birth: An open-label pilot randomized controlled trial". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 11: 18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-18 . PMC 3063235 . PMID 21396090.

- ↑ Ratcliffe, Stephen D.; Baxley, Elizabeth G.; Cline, Matthew K. (2008). Family Medicine Obstetrics. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 273. ISBN 978-0323043069.

- ↑ "Bacterial Vaginosis Treatment and Care". Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ Bacterial vaginosis from National Health Service, UK. Page last reviewed: 03/10/2013

- ↑ Tersigni, C.; Castellani, R.; de Waure, C.; Fattorossi, A.; De Spirito, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Scambia, G.; Di Simone, N. (2014). "Celiac disease and reproductive disorders: meta-analysis of epidemiologic associations and potential pathogenic mechanisms". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (4): 582–593. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu007 . ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 24619876.

- ↑ Saccone G, Berghella V, Sarno L, Maruotti GM, Cetin I, Greco L, Khashan AS, McCarthy F, Martinelli D, Fortunato F, Martinelli P (Oct 9, 2015). "Celiac disease and obstetric complications: a systematic review and metaanalysis". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 214 (2): 225–34. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.09.080. PMID 26432464.

- ↑ "The Gluten Connection". Health Canada. May 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- 1 2 Uzun, S.; Alpsoy, E.; Durdu, M.; Akman, A. (2003). "The clinical course of Behçet's disease in pregnancy: A retrospective analysis and review of the literature". The Journal of Dermatology. 30 (7): 499–502. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00423.x. PMID 12928538. S2CID 12860697.

- 1 2 Jadaon, J.; Shushan, A.; Ezra, Y.; Sela, H. Y.; Ozcan, C.; Rojansky, N. (2005). "Behcet's disease and pregnancy". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 84 (10): 939–944. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00761.x . PMID 16167908. S2CID 22363654.

- 1 2 Compston A, Coles A (October 2008). "Multiple sclerosis". Lancet. 372 (9648): 1502–17. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. PMID 18970977. S2CID 195686659.

- ↑ Multiple Sclerosis: Pregnancy Q&A Archived 2013-10-19 at the Wayback Machine from Cleveland Clinic, retrieved January 2014.

- ↑ Ramagopalan, S. V.; Guimond, C.; Criscuoli, M.; Dyment, D. A.; Orton, S. M.; Yee, I. M.; Ebers, G. C.; Sadovnick, D. (2010). "Congenital Abnormalities and Multiple Sclerosis". BMC Neurology. 10: 115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-115 . PMC 3020672 . PMID 21080921.

- 1 2 3 Pearlstein, Teri (2015-07-01). "Depression during Pregnancy". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 29 (5): 754–764. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.04.004. ISSN 1521-6934. PMID 25976080. S2CID 2932772.

- ↑ Becker, Madeleine; Weinberger, Tal; Chandy, Ann; Schmukler, Sarah (2016-02-15). "Depression During Pregnancy and Postpartum". Current Psychiatry Reports. 18 (3): 32. doi:10.1007/s11920-016-0664-7. ISSN 1535-1645. PMID 26879925. S2CID 38045296.

- ↑ Kwon, Helen L.; Triche, Elizabeth W.; Belanger, Kathleen; Bracken, Michael B. (2006-02-01). "The Epidemiology of Asthma During Pregnancy: Prevalence, Diagnosis, and Symptoms". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 26 (1): 29–62. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2005.11.002. ISSN 0889-8561. PMID 16443142.

- ↑ Murphy, V. E.; Namazy, J. A.; Powell, H.; Schatz, M.; Chambers, C.; Attia, J.; Gibson, P. G. (2011). "A meta-analysis of adverse perinatal outcomes in women with asthma". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 118 (11): 1314–1323. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03055.x. hdl: 1959.13/1052131 . ISSN 1471-0528. PMID 21749633. S2CID 30009033.

- ↑ Mendola, Pauline; Laughon, S. Katherine; Männistö, Tuija I.; Leishear, Kira; Reddy, Uma M.; Chen, Zhen; Zhang, Jun (February 2013). "Obstetric complications among US women with asthma". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 208 (2): 127.e1–127.e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.007. ISSN 0002-9378. PMC 3557554 . PMID 23159695.

- 1 2 Dombrowski, Mitchell P.; Schatz, Michael; Wise, Robert; Momirova, Valerija; Landon, Mark; Mabie, William; Newman, Roger B.; McNellis, Donald; Hauth, John C.; Lindheimer, Marshall; Caritis, Steve N.; Leveno, Kenneth J.; Meis, Paul; Miodovnik, Menachem; Wapner, Ronald J.; Paul, Richard H.; Varner, Michael W.; o'Sullivan, Mary Jo; Thurnau, Gary R.; Conway, Deborah L. (2004). "Asthma During Pregnancy". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 103 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000103994.75162.16. PMID 14704237. S2CID 43265653.

- 1 2 Ali, Z.; Hansen, A. V.; Ulrik, C. S. (2016-05-18). "Exacerbations of asthma during pregnancy: Impact on pregnancy complications and outcome". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 36 (4): 455–461. doi:10.3109/01443615.2015.1065800. ISSN 0144-3615. PMID 26467747. S2CID 207436121.

- ↑ Enriquez, Rachel; Griffin, Marie R.; Carroll, Kecia N.; Wu, Pingsheng; Cooper, William O.; Gebretsadik, Tebeb; Dupont, William D.; Mitchel, Edward F.; Hartert, Tina V. (September 2007). "Effect of maternal asthma and asthma control on pregnancy and perinatal outcomes". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 120 (3): 625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.044 . ISSN 0091-6749. PMID 17658591.

- ↑ Busse, William W. (January 2005). "NAEPP Expert Panel ReportManaging Asthma During Pregnancy: Recommendations for Pharmacologic Treatment—2004 Update". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 115 (1): 34–46. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.023. ISSN 0091-6749. PMID 15637545.

- ↑ Bonham, Catherine A.; Patterson, Karen C.; Strek, Mary E. (February 2018). "Asthma Outcomes and Management During Pregnancy". Chest. 153 (2): 515–527. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.029. ISSN 0012-3692. PMC 5815874 . PMID 28867295.

- ↑ N.C. Thomson, G. Vallance, in Encyclopedia of Respiratory Medicine, 2006, Pages 206-215

- ↑ Neil Pearce, Jeroen Douwes, in Women and Health (Second Edition), 2013

- 1 2 3 Akhtar, M. A.; Saravelos, S. H.; Li, T. C.; Jayaprakasan, K. (2020). "Reproductive Implications and Management of Congenital Uterine Anomalies". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 127 (5): e1–e13. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15968 . ISSN 1471-0528. PMID 31749334.

- ↑ Li, D; Liu, L; Odouli, R (2009). "Presence of depressive symptoms during early pregnancy and the risk of preterm delivery: a prospective cohort study". Human Reproduction. 24 (1): 146–153. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den342 . PMID 18948314.

- ↑ Getahun, D; Ananth, CV; Peltier, MR; Smulian, JC; Vintzileos, AM (2006). "Acute and chronic respiratory diseases in pregnancy: associations with placental abruption". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 195 (4): 1180–4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.027. PMID 17000252.

- ↑ Dombrowski, MP (2006). "Asthma and pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 108 (3 Pt 1): 667–81. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000235059.84188.9c. PMID 16946229.

- ↑ Louik, C; Schatz, M; Hernández-Díaz, S; Werler, MM; Mitchell, AA (2010). "Asthma in Pregnancy and its Pharmacologic Treatment". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 105 (2): 110–7. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2010.05.016. PMC 2953247 . PMID 20674820.

- ↑ Merck. "Overview of Disease During Pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharp & Dohme.

- ↑ Merck. "Cancer during pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharp & Dohme. Archived from the original on 2015-03-28. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ↑ Merck. "High blood pressure during pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharp & Dohme. Archived from the original on 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ↑ Merck. "Liver and gallbladder disorders during pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharpe & Dohme. Archived from the original on 2015-03-16. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ↑ Merck. "Heart disorders during pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharp & Dohme. Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ↑ Merck. "Kidney disorders during pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharp & Dohme. Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ↑ Merck. "Seizure disorders during pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharp & Dohme. Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ↑ Merck. "Liver and gallbladder disorders during pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharpe & Dohme. Archived from the original on 2015-03-16. Retrieved 2013-08-13.