Rubella, also known as German measles or three-day measles, is an infection caused by the rubella virus. This disease is often mild, with half of people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and last for three days. It usually starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body. The rash is sometimes itchy and is not as bright as that of measles. Swollen lymph nodes are common and may last a few weeks. A fever, sore throat, and fatigue may also occur. Joint pain is common in adults. Complications may include bleeding problems, testicular swelling, encephalitis, and inflammation of nerves. Infection during early pregnancy may result in a miscarriage or a child born with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). Symptoms of CRS manifest as problems with the eyes such as cataracts, deafness, as well as affecting the heart and brain. Problems are rare after the 20th week of pregnancy.

In medicine, public health, and biology, transmission is the passing of a pathogen causing communicable disease from an infected host individual or group to a particular individual or group, regardless of whether the other individual was previously infected. The term strictly refers to the transmission of microorganisms directly from one individual to another by one or more of the following means:

Congenital syphilis is syphilis that occurs when a mother with untreated syphilis passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy or at birth. It may present in the fetus, infant, or later. Clinical features vary and differ between early onset, that is presentation before age 2-years of age, and late onset, presentation after age 2-years. Infection in the unborn baby may present as poor growth, non-immune hydrops leading to premature birth or loss of the baby, or no signs. Affected newborns mostly initially have no clinical signs. They may be small and irritable. Characteristic features include a rash, fever, large liver and spleen, a runny and congested nose, and inflammation around bone or cartilage. There may be jaundice, large glands, pneumonia, meningitis, warty bumps on genitals, deafness or blindness. Untreated babies that survive the early phase may develop skeletal deformities including deformity of the nose, lower legs, forehead, collar bone, jaw, and cheek bone. There may be a perforated or high arched palate, and recurrent joint disease. Other late signs include linear perioral tears, intellectual disability, hydrocephalus, and juvenile general paresis. Seizures and cranial nerve palsies may first occur in both early and late phases. Eighth nerve palsy, interstitial keratitis and small notched teeth may appear individually or together; known as Hutchinson's triad.

Genital herpes is a herpes infection of the genitals caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV). Most people either have no or mild symptoms and thus do not know they are infected. When symptoms do occur, they typically include small blisters that break open to form painful ulcers. Flu-like symptoms, such as fever, aching, or swollen lymph nodes, may also occur. Onset is typically around 4 days after exposure with symptoms lasting up to 4 weeks. Once infected further outbreaks may occur but are generally milder.

TORCH syndrome is a cluster of symptoms caused by congenital infection with toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, and other organisms including syphilis, parvovirus, and Varicella zoster. Zika virus is considered the most recent member of TORCH infections.

A genital ulcer is an open sore located on the genital area, which includes the vulva, penis, perianal region, or anus. Genital ulcers are most commonly caused by infectious agents. However, this is not always the case, as a genital ulcer may have noninfectious causes as well.

Condom effectiveness is how effective condoms are at preventing STDs and pregnancy. Correctly using male condoms and other barriers like female condoms and dental dams, every time, can reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and viral hepatitis. They can also provide protection against other diseases that may be transmitted through sex like Zika and Ebola. Using male or female condoms correctly, every time, can also help prevent pregnancy.

The central nervous system (CNS) controls most of the functions of the body and mind. It comprises the brain, spinal cord and the nerve fibers that branch off to all parts of the body. The CNS viral diseases are caused by viruses that attack the CNS. Existing and emerging viral CNS infections are major sources of human morbidity and mortality.

A sexually transmitted infection (STI), also referred to as a sexually transmitted disease (STD) and the older term venereal disease (VD), is an infection that is spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, oral sex, or sometimes manual sex. STIs often do not initially cause symptoms, which results in a risk of passing the infection on to others. Symptoms and signs of STIs may include vaginal discharge, penile discharge, ulcers on or around the genitals, and pelvic pain. Some STIs can cause infertility.

Herpes simplex, often known simply as herpes, is a viral infection caused by the herpes simplex virus. Herpes infections are categorized by the area of the body that is infected. The two major types of herpes are oral herpes and genital herpes, though other forms also exist.

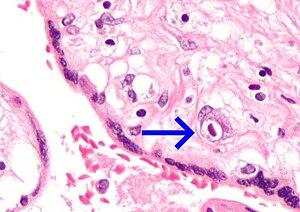

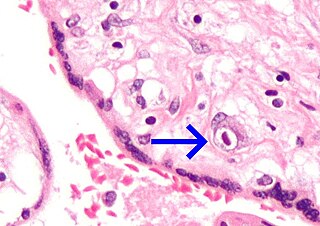

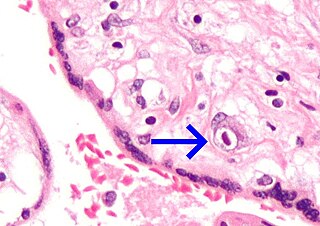

Blueberry muffin baby, also known as extramedullary hematopoiesis, describes a newborn baby with multiple purpura, associated with several non-cancerous and cancerous conditions in which extra blood is produced in the skin. The bumps range from one to seven mm, do not blanch and have a tendency to occur on the head, neck and trunk. They often fade by three to six weeks after birth, leaving brownish marks. When due to a cancer, the bumps tend to be fewer, firmer and larger.

Neonatal herpes simplex, or simply neonatal herpes, is a herpes infection in a newborn baby caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), mostly as a result of vertical transmission of the HSV from an affected mother to her baby. Types include skin, eye, and mouth herpes (SEM), disseminated herpes (DIS), and central nervous system herpes (CNS). Depending on the type, symptoms vary from a fever to small blisters, irritability, low body temperature, lethargy, breathing difficulty, and a large abdomen due to ascites or large liver. There may be red streaming eyes or no symptoms.

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in a newborn baby. Most have no symptoms. Some affected babies are small. Other signs and symptoms include a rash, jaundice, hepatomegaly, retinitis, and seizures. It may lead to loss of hearing or vision, developmental disability, or a small head.

A high-risk pregnancy is one where the mother or the fetus has an increased risk of adverse outcomes compared to uncomplicated pregnancies. No concrete guidelines currently exist for distinguishing “high-risk” pregnancies from “low-risk” pregnancies; however, there are certain studied conditions that have been shown to put the mother or fetus at a higher risk of poor outcomes. These conditions can be classified into three main categories: health problems in the mother that occur before she becomes pregnant, health problems in the mother that occur during pregnancy, and certain health conditions with the fetus.

A pre-existing disease in pregnancy is a disease that is not directly caused by the pregnancy, in contrast to various complications of pregnancy, but which may become worse or be a potential risk to the pregnancy. A major component of this risk can result from necessary use of drugs in pregnancy to manage the disease.

In pregnancy, there is an increased susceptibility and/or severity of several infectious diseases.

HIV in pregnancy is the presence of an HIV/AIDS infection in a woman while she is pregnant. There is a risk of HIV transmission from mother to child in three primary situations: pregnancy, childbirth, and while breastfeeding. This topic is important because the risk of viral transmission can be significantly reduced with appropriate medical intervention, and without treatment HIV/AIDS can cause significant illness and death in both the mother and child. This is exemplified by data from The Centers for Disease Control (CDC): In the United States and Puerto Rico between the years of 2014–2017, where prenatal care is generally accessible, there were 10,257 infants in the United States and Puerto Rico who were exposed to a maternal HIV infection in utero who did not become infected and 244 exposed infants who did become infected.

Neonatal infections are infections of the neonate (newborn) acquired during prenatal development or within the first four weeks of life. Neonatal infections may be contracted by mother to child transmission, in the birth canal during childbirth, or after birth. Neonatal infections may present soon after delivery, or take several weeks to show symptoms. Some neonatal infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, and malaria do not become apparent until much later. Signs and symptoms of infection may include respiratory distress, temperature instability, irritability, poor feeding, failure to thrive, persistent crying and skin rashes.

In the United States, the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS) is responsible for sharing information regarding notifiable diseases. As of 2020, the following are the notifiable diseases in the US as mandated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: