Tiberius Caesar Augustus was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father was the politician Tiberius Claudius Nero and his mother was Livia Drusilla, who would eventually divorce his father, and marry the future-emperor Augustus in 38 BC. Following the untimely deaths of Augustus' two grandsons and adopted heirs, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, Tiberius was designated Augustus' successor. Prior to this, Tiberius had proved himself an able diplomat, and one of the most successful Roman generals: his conquests of Pannonia, Dalmatia, Raetia, and (temporarily) parts of Germania laid the foundations for the empire's northern frontier.

6 was a common year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar. In the Roman Empire, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Lepidus and Lucius Arruntius. The denomination "AD 6" for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

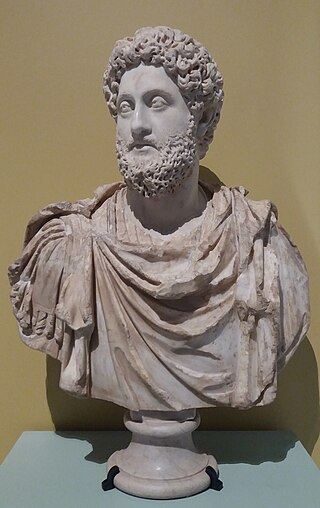

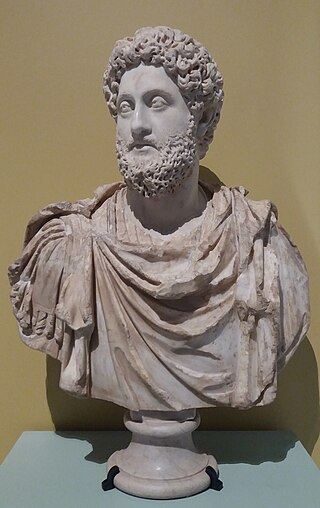

Commodus was a Roman emperor who ruled from 177 to 192. He served jointly with his father Marcus Aurelius from 177 until the latter's death in 180, and thereafter he reigned alone until his assassination. His reign is commonly thought as marking the end of a golden age of peace and prosperity in the history of the Roman Empire.

Marcus Didius Julianus was Roman emperor from March to June 193, during the Year of the Five Emperors. Julianus had a promising political career, governing several provinces, including Dalmatia and Germania Inferior, and defeated the Chauci and Chatti, two invading Germanic tribes. He was even appointed to the consulship in 175 along with Pertinax as a reward, before being demoted by Commodus. After this demotion, his early, promising political career languished.

Lucius Cassius Dio, also known as Dio Cassius, was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the subsequent founding of Rome, the formation of the Republic, and the creation of the Empire up until 229 AD. Written in Ancient Greek over 22 years, Dio's work covers approximately 1,000 years of history. Many of his 80 books have survived intact, or as fragments, providing modern scholars with a detailed perspective on Roman history.

The Praetorian Guard was an elite unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors. During the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard were an escort for high-ranking political officials and were bodyguards for the senior officers of the Roman legions. In 27 BC, after Rome's transition from republic to empire, the first emperor of Rome, Augustus, designated the Praetorians as his personal security escort. For three centuries, the guards of the Roman emperor were also known for their palace intrigues, by whose influence upon imperial politics the Praetorians could overthrow an emperor and then proclaim his successor as the new caesar of Rome. In AD 312, Constantine the Great disbanded the cohortes praetoriae and destroyed their barracks at the Castra Praetoria.

Drusus Julius Caesar was the son of Emperor Tiberius, and heir to the Roman Empire following the death of his adoptive brother Germanicus in AD 19.

Drusus Caesar was the adopted grandson and heir of the Roman emperor Tiberius, alongside his brother Nero. Born into the prominent Julio-Claudian dynasty, Drusus was the son of Tiberius' general and heir, Germanicus. After the deaths of his father and of Tiberius' son, Drusus the Younger, Drusus and his brother Nero Caesar were adopted together by Tiberius in September AD 23. As a result of being heirs of the emperor, he and his brother enjoyed accelerated political careers.

Aerarium, from aes + -ārium, was the name given in Ancient Rome to the public treasury, and in a secondary sense to the public finances.

Praefectus, often with a further qualification, was the formal title of many, fairly low to high-ranking, military or civil officials in the Roman Empire, whose authority was not embodied in their person but conferred by delegation from a higher authority. They did have some authority in their prefecture such as controlling prisons and in civil administration.

Marcus Claudius Marcellus was the eldest son of Gaius Claudius Marcellus and Octavia Minor, sister of Augustus. He was Augustus' nephew and closest male relative, and began to enjoy an accelerated political career as a result. He was educated with his cousin Tiberius and traveled with him to Hispania where they served under Augustus in the Cantabrian Wars. In 25 BC he returned to Rome where he married his cousin Julia, who was the emperor's daughter. Marcellus and Augustus' general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa were the two popular choices as heir to the empire. According to Suetonius, this put Agrippa at odds with Marcellus, and is the reason why Agrippa traveled away from Rome to Mytilene in 23 BC.

Erato was a queen of Armenia from the Artaxiad dynasty. She co-ruled as Roman client queen in 8–5 BC and 2 BC–AD 1 with Tigranes IV. After living in political exile for a number of years, she co-ruled as Roman client queen from 6 until 12 with Tigranes V, her distant paternal relative and possible second husband. She may be viewed as one of the last hereditary rulers of her nation.

Quintus Junius Blaesus was a Roman novus homo who lived during the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius. He was the maternal uncle of Lucius Aelius Sejanus, the Praetorian Prefect of Emperor Tiberius.

The history of the Roman Empire covers the history of ancient Rome from the fall of the Roman Republic in 27 BC until the abdication of Romulus Augustulus in AD 476 in the West, and the Fall of Constantinople in the East in AD 1453. Ancient Rome became a territorial empire while still a republic, but was then ruled by Roman emperors beginning with Augustus, becoming the Roman Empire following the death of the last republican dictator, the first emperor's adoptive father Julius Caesar.

The Imperial Roman army was the military land force of the Roman Empire from 27 BC to 476 AD, and the final incarnation in the long history of the Roman army. This period is sometimes split into the Principate and the Dominate (284–476) periods.

Ariobarzanes II of Atropatene also known as Ariobarzanes of Media; Ariobarzanes of Armenia; Ariobarzanes II; Ariobarzanes II of Media Atropatene and Ariobarzanes was king of Media Atropatene who ruled sometime from 28 BC to 20 BC until 4 and was appointed by the Roman emperor Augustus to serve as a Roman client king of Armenia from 2 AD until 4.

Bulla Felix was an Italian bandit leader of a rebel state to Rome, active around 205–207 AD, during the reign of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus. He united and formed a regiment of over 600 men, among them runaway slaves and imperial freedmen, and eluded capture for more than two years despite pursuit by a force of Roman soldiers under the command of the emperor himself.

Centesima rerum venalium was a 1% tax on goods sold at auction.

The honesta missio was the honorable discharge from the military service in the Roman Empire. The status conveyed particular privileges. Among other things, an honorably discharged legionary was paid discharge money from a treasury established by Augustus, the aerarium militare, which amounted to 12,000 sesterces for the common soldier and around 600,000 sesterces for the primus pilus until the Principate of Caracalla.

Publius Plautius Rufus flourished during the first century, during the Principate of Augustus.