Albanian culture or the culture of Albanians is a term that embodies the artistic, culinary, literary, musical, political and social elements that are representative of ethnic Albanians, which implies not just Albanians of the country of Albania but also Albanians of Kosovo, North Macedonia and Montenegro, where ethnic Albanians are a native population. Albanian culture has been considerably shaped by the geography and history of Albania, Kosovo, parts of Montenegro, parts of North Macedonia, and parts of Northern Greece, traditional homeland of Albanians. It evolved since ancient times in the western Balkans, with its peculiar language, pagan beliefs and practices, way of life and traditions. Albanian culture has also been influenced by the Ancient Greeks, Romans, Byzantines and Ottomans.

A feud, also known in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, private war, or mob war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially families or clans. Feuds begin because one party perceives itself to have been attacked, insulted, injured, or otherwise wronged by another. Intense feelings of resentment trigger an initial retribution, which causes the other party to feel greatly aggrieved and vengeful. The dispute is subsequently fuelled by a long-running cycle of retaliatory violence. This continual cycle of provocation and retaliation usually makes it extremely difficult to end the feud peacefully. Feuds can persist for generations and may result in extreme acts of violence. They can be interpreted as an extreme outgrowth of social relations based in family honor. A mob war is a time when two or more rival families begin open warfare with one another, destroying each other's businesses and assassinating family members. Mob wars are generally disastrous for all concerned, and can lead to the rise or fall of a family.

Isa Boletini was an Albanian revolutionary commander and politician and rilindas from Kosovo.

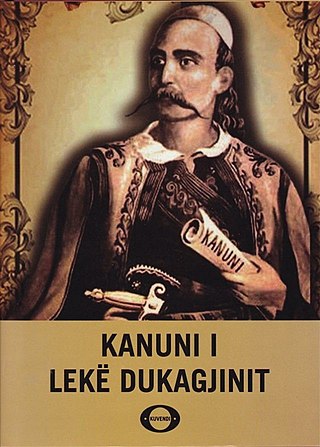

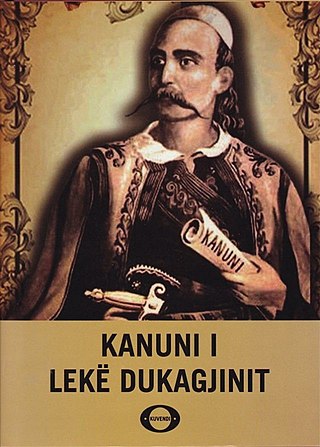

Lekë III Dukagjini (1410–1481), mostly known as Lekë Dukagjini, was a 15th-century member of the Albanian nobility, from the Dukagjini family. A contemporary of Skanderbeg, Dukagjini is known for the Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, a code of law instituted among the tribes of northern Albania. Dukagjini is believed to have been born in Lipjan, Kosovo.

The Kanun is a set of Albanian traditional customary laws, which has directed all the aspects of the Albanian tribal society.

The Vilayet of Scutari, Shkodër or Shkodra was a first-level administrative division (vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire that existed from 1867 to 1913, located in parts of what today is Montenegro and Albania. In the late 19th century it reportedly had an area of 13,800 square kilometres.

Hasan bey Prishtina,, was an Ottoman, later Albanian, politician who served as the 8th prime minister of Albania in December 1921.

Balkan sworn virgins are people who are assigned female at birth and who take a vow of chastity and live as men in patriarchal northern Albanian society, Kosovo and Montenegro. To a lesser extent, the practice exists, or has existed, in other parts of the western Balkans, including Bosnia, Dalmatia (Croatia), Serbia and North Macedonia.

Haxhi Zekë Byberi mostly known as Haxhi Zeka was an Albanian nationalist leader, a member of the League of Prizren, while in 1899 he was part of the establishment and leadership of the League of Peja, another organization seeking protection of Albanians territories from Balkan states. Zeka was assassinated by a Serbian agent in 1902.

Krvna osveta is a law of vendetta among South Slavic peoples in Montenegro and Herzegovina that has been practiced by Serbs, Bosniaks, and Croats throughout history. First recorded in medieval times, the feud is typically sparked by an offense such as murder, rape, assault, or similar wrongdoing. Associates or relatives of the victim, whether they are genuinely wronged or simply perceive it that way, are then prompted to fulfill the social obligation of avenging the victim. The revenge was seen as a way of maintaining one's honor, which was one of the most important aspects of traditional South Slavic culture.

The Code of Lekë Dukagjini (Albanian: Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, also known as the Code of the Mountains is one of the variants of the Albanian customary law transmitted orally. Believed to be much older, it was initially codified by the 15th century Albanian Prince of Dukagjini, Lekë. It was only written and published by the Ottoman administration in the first half of the 19th century in Ottoman Turkish in an attempt to stop the blood feuds. It was then compiled by the Catholic clergy at the turn of the 20th century. The collections of the clergy were published in the Albanian language in the periodical magazines as Albania and Hylli i Dritës. The first complete codification of the usual subject saw its first publication in 1933 in Shkodër, a posthumous work of Shtjefën Gjeçovi who collected it mainly in the villages of Mirdita and its surroundings.

The Ghegs are one of two major ethnic subgroups of Albanians.

Besa is an Albanian cultural precept, usually translated as "pledge of honor", "solemn faith" or "solemn oath", that means "to keep the promise" and "word of honor", regarded as something sacred and inviolable. Besa is of prime importance as a cornerstone of personal and social conduct in the Albanian traditional customary law (Kanun), which has directed all the aspects of Albanian tribal society.

The House of Dukagjini is an Albanian noble family which ruled over an area of Northern Albania and Western Kosovo known as the Principality of Dukagjini in the 14th and 15th centuries. They may have been descendants of the earlier Progoni family, who founded the first Albanian state in recorded history, the Principality of Arbanon. The city of Lezhë was their most important holding.

The Sanjak of Dibra, Debar, or Dibër was one of the sanjaks of the Ottoman Empire. Its capital was Debar, Macedonia. Today, the western part of its territory belongs to Albania and the eastern part to North Macedonia.

The Albanian tribes form a historical mode of social organization (farefisní) in Albania and the southwestern Balkans characterized by a common culture, often common patrilineal kinship ties and shared social ties. The fis stands at the center of Albanian organization based on kinship relations, a concept that can be found among southern Albanians also with the term farë.

Shoshi is a historical Albanian tribe (fis) and region of northern Albania in the lower Shala valley. Shoshi is first recorded as a small settlement in 1485. The fis itself traces its origin to the brothers Gjol and Pep Suma. The community of their descendants gradually grew to control part of the Dukagjin highlands. In the 19th century Shoshi also became a bajrak.

Reconciliation Movement in 1990 a.k.a. (Verrat e Lukes, allegiance, To you I forgave thee blood, Kosovo), was an Albanian all-national movement for blood pardon in Albania and Kosovo. It was organized in 1990 by students, professors and workers' unions in Kosovo. It is part of similar movements throughout Albanian regions since the 1960s.

Isniq is a settlement north of Deçan in Western Kosovo about 45 miles west of Pristina. The village is based on the plains of Dukagjini at the foot of the Accursed Mountains next to the Deçani's White Drin River and is the biggest village in Kosovo. Medicinal plants grow at the mountains of 2656 meters above the sea. Berit Backer wrote a book about the region.

The Vorpsi are an Albanian family native to Tirana and have their first records of a surname recorded in 1650 by Ottoman registries in Tirana and the family's presence has been recorded since. A Muslim family in origin. Very well known, old and respected family from Tirana.