Isa Boletini was an Albanian revolutionary commander and politician and rilindas from Kosovo.

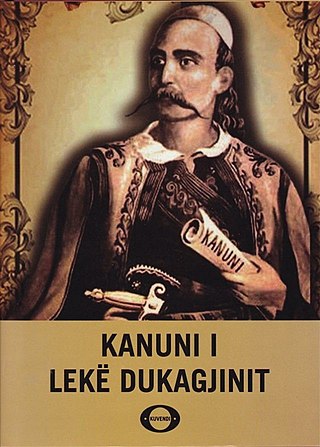

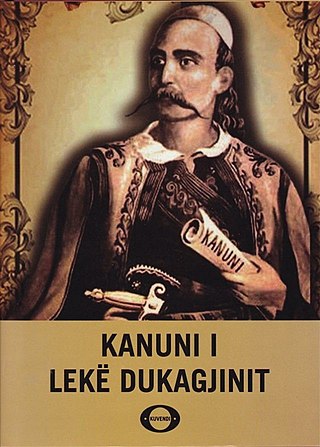

The Kanun is a set of Albanian traditional customary laws, which has directed all the aspects of the Albanian tribal society.

Bajram Curri was an Albanian chieftain, politician and activist who struggled for the independence of Albania, later struggling for Kosovo's incorporation into it following the 1913 Treaty of London. He was posthumously given the title Hero of Albania.

The Vilayet of Kosovo was a first-level administrative division (vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkan Peninsula which included the modern-day territory of Kosovo and the north-western part of the Republic of North Macedonia. The areas today comprising Sandžak (Raška) region of Serbia and Montenegro, although de jure under Ottoman control, were de facto under Austro-Hungarian occupation from 1878 until 1909, as provided under Article 25 of the Treaty of Berlin. Üsküb (Skopje) functioned as the capital of the province and the midway point between Istanbul and its European provinces. Üsküb's population of 32,000 made it the largest city in the province, followed by Prizren, also numbering at 30,000.

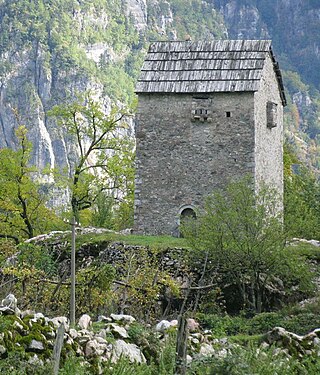

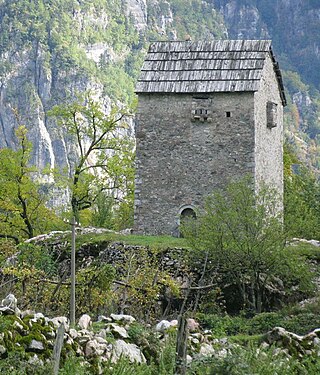

The Vilayet of Scutari, Shkodër or Shkodra was a first-level administrative division (vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire that existed from 1867 to 1913, located in parts of what today is Montenegro and Albania. In the late 19th century it reportedly had an area of 13,800 square kilometres.

In traditional Albanian culture, Gjakmarrja or hakmarrja ("revenge") is the social obligation to kill an offender or a member of their family in order to salvage one's honor. This practice is generally seen as in line with the social code known as the Canon of Lekë Dukagjini or simply the Kanun. The code was originally a "a non-religious code that was used by Muslims and Christians alike."

Sami bey Frashëri or Şemseddin Sâmi was an Ottoman Albanian writer, philosopher, playwright and a prominent figure of the Rilindja Kombëtare, the National Renaissance movement of Albania, together with his two brothers Abdyl and Naim. He also supported Turkish nationalism against its Ottoman counterpart, along with secularism against theocracy.

Shkreli is a historical Albanian tribe and region in the Malësia Madhe region of northern Albania and is majority Catholic. With the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, part of the tribe migrated to Rugova in Western Kosovo beginning around 1700, after which they continued to migrate into the Lower Pešter and Sandžak regions.

The Code of Lekë Dukagjini (Albanian: Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, also known as the Code of the Mountains is one of the variants of the Albanian customary law transmitted orally. Believed to be much older, it was initially codified by the 15th century Albanian Prince of Dukagjini, Lekë. It was only written and published by the Ottoman administration in the first half of the 19th century in Ottoman Turkish in an attempt to stop the blood feuds. It was then compiled by the Catholic clergy at the turn of the 20th century. The collections of the clergy were published in the Albanian language in the periodical magazines as Albania and Hylli i Dritës. The first complete codification of the usual subject saw its first publication in 1933 in Shkodër, a posthumous work of Shtjefën Gjeçovi who collected it mainly in the villages of Mirdita and its surroundings.

The Ghegs are one of two major ethnic subgroups of Albanians. They are differentiated by minor cultural, dialectal, social and religious characteristics. The Ghegs live in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro. The Ghegs speak Gheg Albanian, one of the two main dialects of Albanian language. The social organization of the Ghegs was traditionally tribal, with several distinct tribal groups of Ghegs.

The Sanjak of Dibra, Debar, or Dibër was one of the sanjaks of the Ottoman Empire. Its capital was Debar, Macedonia. Today, the western part of its territory belongs to Albania and the eastern part to North Macedonia.

Mehmed Ferid Pasha was an Ottoman-Albanian statesman. He served as the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 15 January 1903 until 22 July 1908, at the time when the Sultan restored the 1876 Constitution following the Young Turk Revolution. Other than Ottoman Turkish he spoke the Albanian, Arabic, French, Italian, and Greek languages.

The Statutes of Scutari were the highest form of expression of the self-government of Scutari (Shkodër) during Venetian rule. There were other cities in Albania which had statutes but only those of Scutari are preserved in their fullest form. They are composed of 279 chapters written in the Venetian language of the 15th century. They were held in two copies, one in the treasury office of the city and the other on the city court office. Although similar to other Italian and Dalmatian city statutes, they have incorporated many Albanian traditional elements and institutions, such as Besa and Gjakmarrja, developing their own legal traditions through a codification of local customary laws.

Kastrati is a historical Albanian tribe (fis) and region in northwestern Albania. It is part of the Malësia region. Administratively, the region is located in the Malësi e Madhe District, part of the Kastrati municipal unit. The centre of Kastrati is the village of Bajzë. The Kastrati tribe is known to follow the Kanuni i Malësisë së Madhë, a variant of the Kanun. They are proverbally known for their pride - Kastrati Krenar.

The Albanian tribes form a historical mode of social organization (farefisní) in Albania and the southwestern Balkans characterized by a common culture, often common patrilineal kinship ties and shared social ties. The fis stands at the center of Albanian organization based on kinship relations, a concept that can be found among southern Albanians also with the term farë.

Mësonjëtorja or the Albanian School was the first secular school in the Albanian language in Ottoman Albania. It was opened in Korçë during the late Ottoman period. The school building serves as a museum and is located on the north side of Bulevardi Shën Gjergji.

Shoshi is a historical Albanian tribe (fis) and region of northern Albania in the lower Shala valley. Shoshi is first recorded as a small settlement in 1485. The fis itself traces its origin to the brothers Gjol and Pep Suma. The community of their descendants gradually grew to control part of the Dukagjin highlands. In the 19th century Shoshi also became a bajrak.

The Traditions of Albania refers to the traditions, beliefs, values and customs that belong within the culture of the Albanian people. Those traditions have influenced daily life in Albania for centuries and are still practiced throughout Albania, Balkans, and Diaspora. The Albanians have a unique culture, which progressed over the centuries through its strategic geography and its distinct historical evolution.

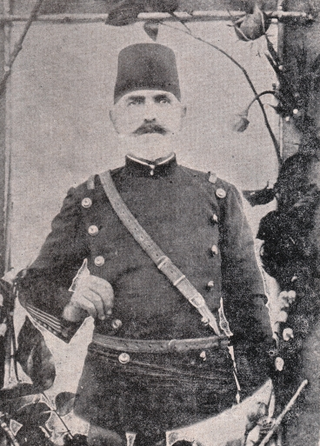

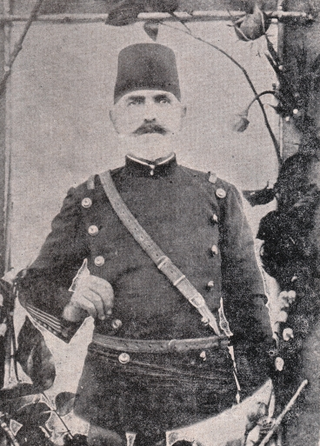

Shemsi Pasha (1846-1908) was an Ottoman-Albanian general.

The Taksim meeting alternatively known as the Taksim Plot and less commonly as the Taksim Assembly was a secret meeting held in January 1912 by Albanian nationalist deputies of the Ottoman parliament and other prominent Albanian political figures. The event gets its name from Taksim Square because of the location of the house where it was held. The meeting was organized on the initiative of Hasan Prishtina and Ismail Qemali, Albanian politicians, who invited most of the MPs of Albanian origin and aimed at launching an armed general uprising in Albanian territories against the central government headed by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). The meeting followed two other Albanian uprisings of 1910 in the Vilayet of Kosovo and 1911 in the mountains of upper Shkodra. The Taksim meeting resulted in an uprising the same year, with armed uprisings in Shkodër, Lezhë, Mirditë, Krujë and other Albanian provinces, which exceeded the organizers' expectations. The biggest uprising was in Kosovo, where the rebels were more organized and managed to take over important cities like Prizren, Peja, Gjakova, Mitrovica and others.