Anacamptis pyramidalis, the pyramidal orchid, is a perennial herbaceous plant belonging to the genus Anacamptis of the family Orchidaceae. The scientific name Anacamptis derives from Greek ανακάμτειν 'anakamptein' meaning 'bend forward', while the Latin name pyramidalis refers to the pyramidal form of the inflorescence.

A pollinator is an animal that moves pollen from the male anther of a flower to the female stigma of a flower. This helps to bring about fertilization of the ovules in the flower by the male gametes from the pollen grains.

In biology, coevolution occurs when two or more species reciprocally affect each other's evolution through the process of natural selection. The term sometimes is used for two traits in the same species affecting each other's evolution, as well as gene-culture coevolution.

Angraecum, also known as comet orchid, is a genus of the family Orchidaceae native to tropical and South Africa, as well as Sri Lanka. It contains 223 species.

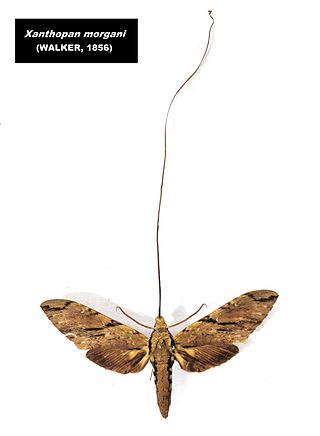

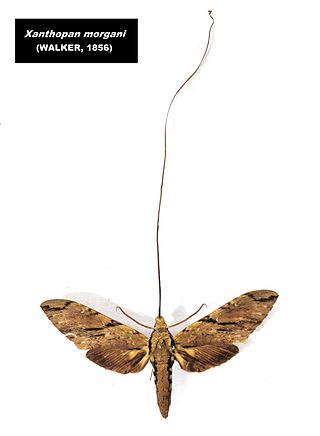

The Sphingidae are a family of moths commonly called sphinx moths, also colloquially known as hawk moths, with many of their caterpillars known as "hornworms"; it includes about 1,450 species. It is best represented in the tropics, but species are found in every region. They are moderate to large in size and are distinguished among moths for their agile and sustained flying ability, similar enough to that of hummingbirds as to be reliably mistaken for them. Their narrow wings and streamlined abdomens are adaptations for rapid flight. The family was named by French zoologist Pierre André Latreille in 1802.

Self-pollination is a form of pollination in which pollen from the same plant arrives at the stigma of a flower or at the ovule. There are two types of self-pollination: in autogamy, pollen is transferred to the stigma of the same flower; in geitonogamy, pollen is transferred from the anther of one flower to the stigma of another flower on the same flowering plant, or from microsporangium to ovule within a single (monoecious) gymnosperm. Some plants have mechanisms that ensure autogamy, such as flowers that do not open (cleistogamy), or stamens that move to come into contact with the stigma. The term selfing that is often used as a synonym, is not limited to self-pollination, but also applies to other type of self-fertilization.

The concept of predictive power, the power of a scientific theory to generate testable predictions, differs from explanatory power and descriptive power in that it allows a prospective test of theoretical understanding.

Entomophily or insect pollination is a form of pollination whereby pollen of plants, especially but not only of flowering plants, is distributed by insects. Flowers pollinated by insects typically advertise themselves with bright colours, sometimes with conspicuous patterns leading to rewards of pollen and nectar; they may also have an attractive scent which in some cases mimics insect pheromones. Insect pollinators such as bees have adaptations for their role, such as lapping or sucking mouthparts to take in nectar, and in some species also pollen baskets on their hind legs. This required the coevolution of insects and flowering plants in the development of pollination behaviour by the insects and pollination mechanisms by the flowers, benefiting both groups. Both the size and the density of a population are known to affect pollination and subsequent reproductive performance.

Zoophily, or zoogamy, is a form of pollination whereby pollen is transferred by animals, usually by invertebrates but in some cases vertebrates, particularly birds and bats, but also by other animals. Zoophilous species frequently have evolved mechanisms to make themselves more appealing to the particular type of pollinator, e.g. brightly colored or scented flowers, nectar, and appealing shapes and patterns. These plant-animal relationships are often mutually beneficial because of the food source provided in exchange for pollination.

Nectar is a sugar-rich liquid produced by plants in glands called nectaries or nectarines, either within the flowers with which it attracts pollinating animals, or by extrafloral nectaries, which provide a nutrient source to animal mutualists, which in turn provide herbivore protection. Common nectar-consuming pollinators include mosquitoes, hoverflies, wasps, bees, butterflies and moths, hummingbirds, honeyeaters and bats. Nectar plays a crucial role in the foraging economics and evolution of nectar-eating species; for example, nectar foraging behavior is largely responsible for the divergent evolution of the African honey bee, A. m. scutellata and the western honey bee.

Pollination syndromes are suites of flower traits that have evolved in response to natural selection imposed by different pollen vectors, which can be abiotic or biotic, such as birds, bees, flies, and so forth through a process called pollinator-mediated selection. These traits include flower shape, size, colour, odour, reward type and amount, nectar composition, timing of flowering, etc. For example, tubular red flowers with copious nectar often attract birds; foul smelling flowers attract carrion flies or beetles, etc.

Xanthopan is a monotypic genus of sphinx moth, with Xanthopan morganii, commonly called Morgan's sphinx moth, as its sole species. It is a very large sphinx moth from Southern Africa and Madagascar. Little is known about its biology, though the adults have been found to visit orchids and are one of the main pollinators of several of the Madagascar endemic baobab (Adansonia) species, Adansonia perrieri or Perrier's baobab.

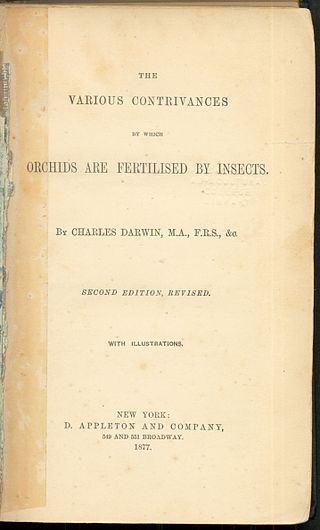

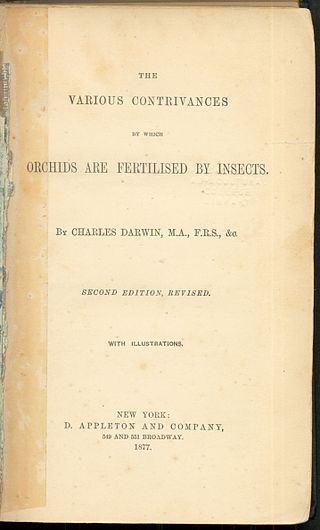

Fertilisation of Orchids is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin published on 15 May 1862 under the full explanatory title On the Various Contrivances by Which British and Foreign Orchids Are Fertilised by Insects, and On the Good Effects of Intercrossing. Darwin's previous book, On the Origin of Species, had briefly mentioned evolutionary interactions between insects and the plants they fertilised, and this new idea was explored in detail. Field studies and practical scientific investigations that were initially a recreation for Darwin—a relief from the drudgery of writing—developed into enjoyable and challenging experiments. Aided in his work by his family, friends, and a wide circle of correspondents across Britain and worldwide, Darwin tapped into the contemporary vogue for growing exotic orchids.

Aerangis fastuosa, commonly known as the 'magnificent Aerangis', is a species of epiphytic orchid endemic to Madagascar. It is widespread across Madagascar, stretching from the eastern coastal forests across to the south and along the central plateau. Aerangis fastuosa belongs to the family Orchidaceae, subtribe Aerangidinae.

Coelonia solani is a moth of the family Sphingidae. It is known from Mauritius, Réunion, Madagascar and the Comoro Islands. It is a pollinator of some species of baobab in Madagascar, including Adansonia za.

The Botanical Garden of Faial is an ecological garden, component of the Faial Nature Park, established in 1986 to educate and protect the biodiversity common on Faial, an island of the Azores archipelago.

Floral biology is an area of ecological research that studies the evolutionary factors that have moulded the structures, behaviour and physiological aspects involved in the flowering of plants. The field is broad and interdisciplinary and involves research requiring expertise from multiple disciplines that can include botany, ethology, biochemistry, and entomology. A slightly narrower area of research within floral biology is sometimes called pollination biology or anthecology.

A nectar spur is a hollow extension of a part of a flower. The spur may arise from various parts of the flower: the sepals, petals, or hypanthium, and often contain tissues that secrete nectar (nectaries). Nectar spurs are present in many clades across the angiosperms, and are often cited as an example of convergent evolution.

The pollination of orchids is a complex chapter in the biology of this family of plants that are distinguished by the complexity of their flowers and by intricate ecological interactions with their pollinator agents. It has captured the attention of numerous scientists over time, including Charles Darwin, father of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin published in 1862 the first observations of the fundamental role of insects in orchid pollination, in his book The Fertilization of Orchids. Darwin stated that the varied stratagems orchids use to attract their pollinators transcend the imagination of any human being.

Angraecum longicalcar, also known as the long spurred Angraecum, is a large critically endangered orchid endemic to the Central Highlands of Madagascar. This lithophytic species is noteworthy for its exceptionally long 40 cm nectar spur, rivalling that of the famous Darwins' orchid , and as such may have the longest spur of any orchid species.