Ascomycota is a phylum of the kingdom Fungi that, together with the Basidiomycota, forms the subkingdom Dikarya. Its members are commonly known as the sac fungi or ascomycetes. It is the largest phylum of Fungi, with over 64,000 species. The defining feature of this fungal group is the "ascus", a microscopic sexual structure in which nonmotile spores, called ascospores, are formed. However, some species of Ascomycota are asexual and thus do not form asci or ascospores. Familiar examples of sac fungi include morels, truffles, brewers' and bakers' yeast, dead man's fingers, and cup fungi. The fungal symbionts in the majority of lichens such as Cladonia belong to the Ascomycota.

An endolith or endolithic is an organism that is able to acquire the necessary resources for growth in the inner part of a rock, mineral, coral, animal shells, or in the pores between mineral grains of a rock. Many are extremophiles, living in places long considered inhospitable to life. The distribution, biomass, and diversity of endolith microorganisms are determined by the physical and chemical properties of the rock substrate, including the mineral composition, permeability, the presence of organic compounds, the structure and distribution of pores, water retention capacity, and the pH. Normally, the endoliths colonize the areas within lithic substrates to withstand intense solar radiation, temperature fluctuations, wind, and desiccation. They are of particular interest to astrobiologists, who theorize that endolithic environments on Mars and other planets constitute potential refugia for extraterrestrial microbial communities.

Saccharomycotina is a subdivision (subphylum) of the division (phylum) Ascomycota in the kingdom Fungi. It comprises most of the ascomycete yeasts. The members of Saccharomycotina reproduce by budding and they do not produce ascocarps.

Dothideomycetes is the largest and most diverse class of ascomycete fungi. It comprises 11 orders 90 families, 1,300 genera and over 19,000 known species. Wijayawardene et al. in 2020 added more orders to the class.

A dimorphic fungus is a fungus that can exist in the form of both mold and yeast. As this is usually brought about by a change in temperature, this fungus type is also described as a thermally dimorphic fungus. An example is Talaromyces marneffei, a human pathogen that grows as a mold at room temperature, and as a yeast at human body temperature.

Trebouxia is a unicellular green alga. It is a photosynthetic organism that can exist in almost all habitats found in polar, tropical, and temperate regions. It can either exist in a symbiotic relationship with fungi in the form of lichen or it can survive independently as a free-living organism alone or in colonies. Trebouxia is the most common photobiont in extant lichens. It is a primary producer of marine, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. It uses carotenoids and chlorophyll a and b to harvest energy from the sun and provide nutrients to various animals and insects.

Verrucariales is an order of ascomycetous fungi within the subclass Chaetothyriomycetidae of the class Eurotiomycetes. Although most of the Verrucariales are lichenised, the family Sarcopyreniaceae consists of 11 species of lichenicolous (lichen-dwelling) fungi.

Verrucariaceae is a family of lichens and a few non-lichenised fungi in the order Verrucariales. The lichens have a wide variety of thallus forms, from crustose (crust-like) to foliose (bushy) and squamulose (scaly). Most of them grow on land, some in freshwater and a few in the sea. Many are free-living but there are some species that are parasites on other lichens, while one marine species always lives together with a leafy green alga.

Lithoglypha is a fungal genus in the family Acarosporaceae. It is monotypic, containing the single species Lithoglypha aggregata, a saxicolous (rock-dwelling), crustose lichen found in South Africa.

Antarctica is one of the most physically and chemically extreme terrestrial environments to be inhabited by lifeforms. The largest plants are mosses, and the largest animals that do not leave the continent are a few species of insects.

Lichenothelia is a genus of fungi in the family Lichenotheliaceae.

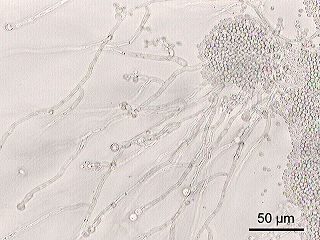

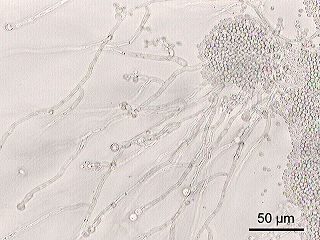

Black yeasts, sometimes also black fungi, dematiaceous fungi, microcolonial fungi or meristematic fungi is a diverse group of slow-growing microfungi which reproduce mostly asexually. Only few genera reproduce by budding cells, while in others hyphal or meristematic (isodiametric) reproduction is preponderant. Black yeasts share some distinctive characteristics, in particular a dark colouration (melanisation) of their cell wall. Morphological plasticity, incrustation of the cell wall with melanins and presence of other protective substances like carotenoids and mycosporines represent passive physiological adaptations which enable black fungi to be highly resistant against environmental stresses. The term "polyextremotolerance" has been introduced to describe this phenotype, an example of which is the species Aureobasidium pullulans. Presence of 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene melanin in the cell wall confers to the microfungi their characteristic olivaceous to dark brown/black colour.

The wildlife of Antarctica are extremophiles, having adapted to the dryness, low temperatures, and high exposure common in Antarctica. The extreme weather of the interior contrasts to the relatively mild conditions on the Antarctic Peninsula and the subantarctic islands, which have warmer temperatures and more liquid water. Much of the ocean around the mainland is covered by sea ice. The oceans themselves are a more stable environment for life, both in the water column and on the seabed.

Roseli Ocampo-Friedmann was a Filipino-American microbiologist and botanist who specialized in the study of cyanobacteria and extremophiles. Her work has been cited in work exploring the terraforming of Mars.

Teratosphaeriaceae is a family of fungi in the order Mycosphaerellales.

A lichenicolous fungus is a member of a specialised group of fungi that live exclusively on lichens as their host organisms. These fungi, comprising over 2,000 known species across 280 genera, exhibit a wide range of ecological strategies, including parasitism, commensalism, and mutualism. They can be found in diverse environments worldwide, from tropical to polar regions, and play important roles in lichen ecology and biodiversity. Lichenicolous fungi are classified into several taxonomic groups, with the majority belonging to the Ascomycota and a smaller portion to the Basidiomycota. Their interactions with host lichens range from mild parasitism to severe pathogenicity, sometimes causing significant damage to lichen communities.

Cryomyces minteri is a fungus of uncertain placement in the class Dothideomycetes, division Ascomycota. The rock-inhabiting fungus that was discovered in the McMurdo Dry Valleys located in Antarctica, on fragments of rock colonized by a local cryptoendolithic community.

Lichenostigmatales is an order of fungi in the class Arthoniomycetes. It contains the single family Phaeococcomycetaceae. Lichenostigmatales was circumscribed in 2014 by Damien Ertz, Paul Diederich, and James D. Lawrey, with genus Lichenostigma assigned as the type. Using molecular phylogenetics, they identified a lineage of taxa in the Arthoniomycetes that were phylogenetically distinct from the order Arthoniales. Species in the Lichenostigmatales include black yeasts, lichenicolous, and melanised rock-inhabiting species.

Catenarina is a genus of lichen-forming fungi in the family Teloschistaceae consisting of three species. These crustose lichens are characterized by their reddish-brown pigmentation and the presence of the secondary compound 7-chlorocatenarin. The genus is found in the southernmost regions of the Southern Hemisphere, including Antarctica, southern Patagonia, and the Kerguelen Islands.

Erinacellus is a genus of lichen-forming fungi of uncertain familial placement in the order Peltigerales. It consists of two species. These lichens are characterised by their dense, cushion-like growths composed of erect, thread-like branches, which resemble miniature hedgehogs. The genus was established in 2014 and is named after the hedgehog genus Erinaceus, reflecting its appearance. Erinacellus forms a symbiotic relationship with Hyphomorpha, a type of cyanobacteria. While the genus is placed within the order Peltigerales, its exact position within this group remains uncertain. The two species, E. dendroides and E. schmidtii, are found in different parts of the world, with E. dendroides occurring in New Zealand and North America, and E. schmidtii in Thailand and Sri Lanka. These lichens typically grow in moist environments, such as coastal areas and tropical regions, and can be found on both rocks and tree bark.