Megachile rotundata, the alfalfa leafcutting bee, is a European bee that has been introduced to various regions around the world. As a solitary bee species, it does not build colonies or store honey, but is a very efficient pollinator of alfalfa, carrots, other vegetables, and some fruits. Because of this, farmers often use M. rotundata as a pollination aid by distributing M. rotundata prepupae around their crops. Each female constructs and provisions her own nest, which is built in old trees or log tunnels. Being a leafcutter bee, these nests are lined with cut leaves. These bees feed on pollen and nectar and display sexual dimorphism. This species has been known to bite and sting, but it poses no overall danger unless it is threatened or harmed, and its sting has been described as half as painful as a honey bee's.

Megachilidae is a cosmopolitan family of mostly solitary bees. Characteristic traits of this family are the restriction of their pollen-carrying structure to the ventral surface of the abdomen, and their typically elongated labrum. Megachilid genera are most commonly known as mason bees and leafcutter bees, reflecting the materials from which they build their nest cells ; a few collect plant or animal hairs and fibers, and are called carder bees, while others use plant resins in nest construction and are correspondingly called resin bees. All species feed on nectar and pollen, but a few are kleptoparasites, feeding on pollen collected by other megachilid bees. Parasitic species do not possess scopae. The motion of Megachilidae in the reproductive structures of flowers is energetic and swimming-like; this agitation releases large amounts of pollen.

Mason bee is a name now commonly used for species of bees in the genus Osmia, of the family Megachilidae. Mason bees are named for their habit of using mud or other "masonry" products in constructing their nests, which are made in naturally occurring gaps such as between cracks in stones or other small dark cavities. When available, some species preferentially use hollow stems or holes in wood made by wood-boring insects.

Xylocopa virginica, sometimes referred to as the eastern carpenter bee, extends through the eastern United States and into Canada. They are sympatric with Xylocopa micans in much of southeastern United States. They nest in various types of wood and eat pollen and nectar. In X. virginica, dominant females do not focus solely on egg-laying, as in other bee species considered to have "queens". Instead, dominant X. virginica females are responsible for a full gamut of activities including reproduction, foraging, and nest construction, whereas subordinate bees may engage in little activity outside of guarding the nest.

Anthidium is a genus of bees often called carder or potter bees, who use conifer resin, plant hairs, mud, or a mix of them to build nests. They are in the family Megachilidae which is cosmopolitan in distribution and made up of species that are mostly solitary bees with pollen-carrying scopa that are only located on the ventral surface of the abdomen. Other bee families have the pollen-carrying structures on the hind legs. Typically species of Anthidium feed their brood on pollen and nectar from plants. Anthidium florentinum is distinguished from most of its relatives by yellow or brick-red thoracic bands. They fly all summer and make the nests in holes in the ground, walls or trees, with hairs plucked from plants.

Osmia bicornis is a species of mason bee, and is known as the red mason bee due to its covering of dense gingery hair. It is a solitary bee that nests in holes or stems and is polylectic, meaning it forages pollen from various different flowering plants. These bees can be seen aggregating together and nests in preexisting hollows, choosing not to excavate their own. These bees are not aggressive; they will only sting if handled very roughly and are safe to be closely observed by children. Females only mate once, usually with closely related males. Further, females can determine the sex ratio of their offspring based on their body size, where larger females will invest more in diploid females eggs than small bees. These bees also have trichromatic colour vision and are important pollinators in agriculture.

Xylocopa sonorina, the valley carpenter bee or Hawaiian carpenter bee, is a species of carpenter bee found from western Texas to northern California, and the eastern Pacific islands. Females are black while males are golden-brown with green eyes.

Trigona spinipes is a species of stingless bee. It occurs in Brazil, where it is called arapuá, aripuá, irapuá, japurá or abelha-cachorro ("dog-bee"). The species name means "spiny feet" in Latin. Trigona spinipes builds its nest on trees, out of mud, resin, wax, and assorted debris, including dung. Therefore, its honey is not fit for consumption, even though it is reputed to be of good quality by itself, and is used in folk medicine. Colonies may have from 5,000 to over 100,000 workers.

Anthidium florentinum, one of several European wool carder bees, is a territorial species of bee in the family Megachilidae, the leaf-cutter, carder, or mason bees.

Amegilla dawsoni, sometimes called the Dawson's burrowing bee, is a species of bee that nests by the thousands in arid claypans in Western Australia. It is a long tongued bee, of the tribe Anthophorini and genus Amegilla, the second largest genus in Anthophorini.

The California carpenter bee, Xylocopa californica, is a species of carpenter bee in the order Hymenoptera, and it is native to western North America.

Anthidium manicatum, commonly called the European wool carder bee, is a species of bee in the family Megachilidae, the leaf-cutter bees or mason bees.

Lasioglossum zephyrus is a sweat bee of the family Halictidae, found in the U.S. and Canada. It appears in the literature primarily under the misspelling "zephyrum". It is considered a primitively eusocial bee, although it may be facultatively solitary. The species nests in burrows in the soil.

Eulaema meriana is a large-bodied bee species in the tribe Euglossini, otherwise known as the orchid bees. The species is a solitary bee and is native to tropical Central and South America. The male collects fragrances from orchid flowers, which it stores in hollows in its hind legs. Orchids can be deceptive by mimicking the form of a female and her sex pheromone, thus luring male bees or wasps. Pollination will take place as the males attempt to mate with the labellum, or the tip petal of the flower. Male E. meriana are territorial and have a particular perch on a tree trunk where it displays to attract a female. After mating, the female builds a nest with urn-shaped cells made with mud, feces, and plant resin, and provisions these with nectar and pollen before laying an egg in each. These bees also have complex foraging and wing buzzing behaviors and are part of a mimicry complex.

Euglossa cordata is a primitively eusocial orchid bee of the American tropics. The species is known for its green body color and ability to fly distances of over 50 km. Males mostly disperse and leave their home nests, while females have been observed to possess philopatric behavior. Because of this, sightings are rare and little is known about the species. However, it has been observed that adults who pollinate certain species of orchids will become intoxicated during the pollination.

Xylocopa sulcatipes is a large Arabian carpenter bee. These multivoltine bees take part in social nesting and cooperative nesting. They are metasocial carpenter bees that nest in thin dead branches. One or more cooperating females build many brood cells. They have been extensively studied in Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Euglossa imperialis is a bee species in the family Apidae. It is considered to be one of the most important pollinators to many Neotropical orchid species in mainland tropical America. It is also one of the most common non-parasitic euglossine species in lowland Panama. E. imperialis, unlike many other bee species, is not a social bee in the sense that there is no apparent morphological or physiological division within the species to distinguish individual bees to be part of a worker or reproductive caste.

Xylocopa pubescens is a species of large carpenter bee. Females form nests by excavation with their mandibles, often in dead or soft wood. X. pubescens is commonly found in areas extending from India to Northeast and West Africa. It must reside in these warm climates because it requires a minimum ambient temperature of 18 °C (64 °F) in order to forage.

Macropis nuda is a ground nesting, univoltine bee native to northern parts of North America. Thus, this species cocoons as pupae and hibernates over the winter. The species is unusual as it is an oligolectic bee, foraging exclusively for floral oils and pollen from Primulaceae of the species Lysimachia ciliata.

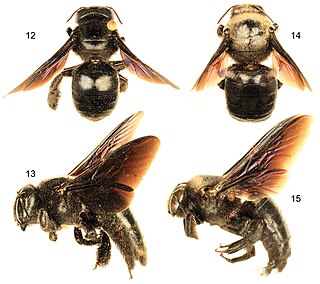

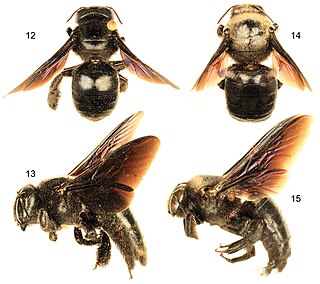

Xylocopa micans, also known as the southern carpenter bee, is a species of bee within Xylocopa, the genus of carpenter bees. The southern carpenter bee can be found mainly in the coastal and gulf regions of the southeastern United States, as well as Mexico and Guatemala. Like all Xylocopa bees, X. micans bees excavate nests in woody plant material. However, unlike its sympatric species Xylocopa virginica, X. micans has not been found to construct nest galleries in structural timbers of building, making it less of an economic nuisance to humans. Carpenter bees have a wide range of mating strategies between different species. The southern carpenter bee exhibits a polymorphic mating strategy, with its preferred method of mating changing as the season progresses from early spring to mid summer. Like most bees in its genus, the southern carpenter bee is considered a solitary bee because it does not live in colonies.