Campylocephalus is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Campylocephalus have been discovered in deposits ranging from the Carboniferous period in the Czech Republic to the Permian period of Russia. The generic name is composed of the Greek words καμπύλος (kampýlos), meaning "curved", and κεφαλή (kephalē), meaning "head".

Watsonichthys is an extinct genus of prehistoric bony fish that lived during the Tournaisian age to possibly the Asselian age in what is now Europe and possibly Namibia. It is named after David Meredith Seares Watson.

Sundayichthys is an extinct genus of prehistoric bony fish that lived during the Carboniferous period in what is now South Africa. Fossils were recovered from the Upper Witteberg Series.

Igornella is an extinct genus of prehistoric bony fish that lived during the Gzhelian (Stephanian) to Asselian ages in what is now France (Burgundy).

Tylonautilus is an extinct genus in the nautiloid order Nautilida from the Lower Carboniferous of Europe and Permian of Japan.

Fossils of many types of water-dwelling animals from the Devonian period are found in deposits in the U.S. state of Michigan. Among the more commonly occurring specimens are bryozoans, corals, crinoids, and brachiopods. Also found, but not so commonly, are armored fish called placoderms, snails, sharks, stromatolites, trilobites and blastoids.

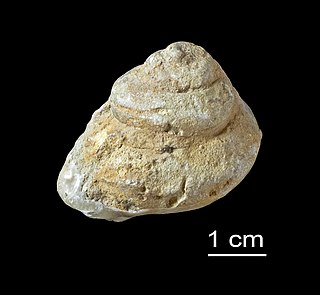

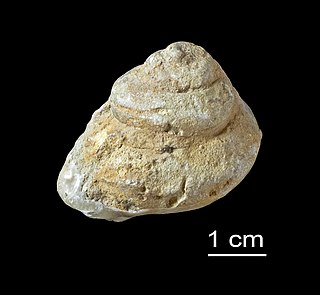

Holopea is an extinct genus of fossil sea snails, Paleozoic gastropod mollusks in the family Holopeidae.

Paleontology in Michigan refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Michigan. During the Precambrian, the Upper Peninsula was home to filamentous algae. The remains it left behind are among the oldest known fossils in the world. During the early part of the Paleozoic Michigan was covered by a shallow tropical sea which was home to a rich invertebrate fauna including brachiopods, corals, crinoids, and trilobites. Primitive armored fishes and sharks were also present. Swamps covered the state during the Carboniferous. There are little to no sedimentary deposits in the state for an interval spanning from the Permian to the end of the Neogene. Deposition resumed as glaciers transformed the state's landscape during the Pleistocene. Michigan was home to large mammals like mammoths and mastodons at that time. The Holocene American mastodon, Mammut americanum, is the Michigan state fossil. The Petoskey stone, which is made of fossil coral, is the state stone of Michigan.

Paleontology in Kentucky refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Kentucky.

Paleontology in Indiana refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Indiana. Indiana's fossil record stretches back to the Precambrian, when the state was inhabited by microbes. More complex organisms came to inhabit the state during the early Paleozoic era. At that time the state was covered by a warm shallow sea that would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, cephalopods, crinoids, and trilobites. During the Silurian period the state was home to significant reef systems. Indiana became a more terrestrial environment during the Carboniferous, as an expansive river system formed richly vegetated deltas where amphibians lived. There is a gap in the local rock record from the Permian through the Mesozoic. Likewise, little is known about the early to middle Cenozoic era. During the Ice Age however, the state was subject to glacial activity, and home to creatures like short-faced bears, camels, mammoths, and mastodons. After humans came to inhabit the state, Native Americans interpreted the fossil proboscidean remains preserved near Devil's Lake as the bones of water monsters. After the advent of formal scientific investigation one paleontological survey determined that the state was home to nearly 150 different kinds of prehistoric plants.

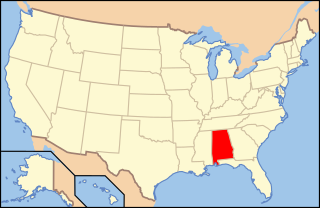

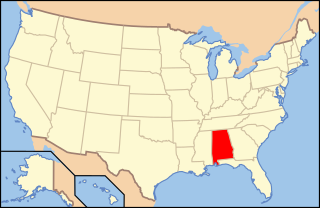

Paleontology in Alabama refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Alabama. Pennsylvanian plant fossils are common, especially around coal mines. During the early Paleozoic, Alabama was at least partially covered by a sea that would end up being home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and graptolites. During the Devonian the local seas deepened and local wildlife became scarce due to their decreasing oxygen levels.

Paleontology in Missouri refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Missouri. The geologic column of Missouri spans all of geologic history from the Precambrian to present with the exception of the Permian, Triassic, and Jurassic. Brachiopods are probably the most common fossils in Missouri.

Paleontology in Texas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Texas. Author Marian Murray has said that "Texas is as big for fossils as it is for everything else." Some of the most important fossil finds in United States history have come from Texas. Fossils can be found throughout most of the state. The fossil record of Texas spans almost the entire geologic column from Precambrian to Pleistocene. Shark teeth are probably the state's most common fossil. During the early Paleozoic era Texas was covered by a sea that would later be home to creatures like brachiopods, cephalopods, graptolites, and trilobites. Little is known about the state's Devonian and early Carboniferous life. Evidence indicates that during the late Carboniferous the state was home to marine life, land plants and early reptiles. During the Permian, the seas largely shrank away, but nevertheless coral reefs formed in the state. The rest of Texas was a coastal plain inhabited by early relatives of mammals like Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus. During the Triassic, a great river system formed in the state that was inhabited by crocodile-like phytosaurs. Little is known about Jurassic Texas, but there are fossil aquatic invertebrates of this age like ammonites in the state. During the Early Cretaceous local large sauropods and theropods left a great abundance of footprints. Later in the Cretaceous, the state was covered by the Western Interior Seaway and home to creatures like mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and few icthyosaurs. Early Cenozoic Texas still contained areas covered in seawater where invertebrates and sharks lived. On land the state would come to be home to creatures like glyptodonts, mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, giant ground sloths, titanotheres, uintatheres, and dire wolves. Archaeological evidence suggests that local Native Americans knew about local fossils. Formally trained scientists were already investigating the state's fossils by the late 1800s. In 1938, a major dinosaur footprint find occurred near Glen Rose. Pleurocoelus was the Texas state dinosaur from 1997 to 2009, when it was replaced by Paluxysaurus jonesi after the Texan fossils once referred to the former species were reclassified to a new genus.

Paleontology in New Mexico refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of New Mexico. The fossil record of New Mexico is exceptionally complete and spans almost the entire stratigraphic column. More than 3,300 different kinds of fossil organisms have been found in the state. Of these more than 700 of these were new to science and more than 100 of those were type species for new genera. During the early Paleozoic, southern and western New Mexico were submerged by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, cartilaginous fishes, corals, graptolites, nautiloids, placoderms, and trilobites. During the Ordovician the state was home to algal reefs up to 300 feet high. During the Carboniferous, a richly vegetated island chain emerged from the local sea. Coral reefs formed in the state's seas while terrestrial regions of the state dried and were home to sand dunes. Local wildlife included Edaphosaurus, Ophiacodon, and Sphenacodon.

Paleontology in Idaho refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Idaho. The fossil record of Idaho spans much of the geologic column from the Precambrian onward. During the Precambrian, bacteria formed stromatolites while worms left behind trace fossils. The state was mostly covered by a shallow sea during the majority of the Paleozoic era. This sea became home to creatures like brachiopods, corals and trilobites. Idaho continued to be a largely marine environment through the Triassic and Jurassic periods of the Mesozoic era, when brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, ichthyosaurs and sharks inhabited the local waters. The eastern part of the state was dry land during the ensuing Cretaceous period when dinosaurs roamed the area and trees grew which would later form petrified wood.

Cystoporida, also known as Cystoporata or cystoporates, are an extinct order of Paleozoic bryozoans in the class Stenolaemata. Their fossils are found from Ordovician to Triassic strata.

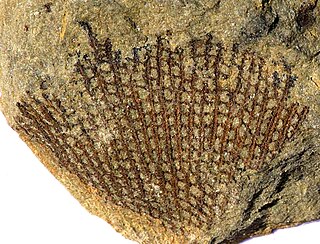

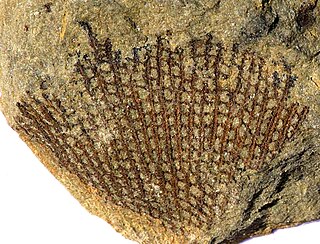

Fenestellidae is a family of bryozoans belonging to the order Fenestrida. The skeleton of its colonies consists of stiff branches that are interconnected by narrower crossbars. The individuals of the colony inhabit one side of the branches in two parallel rows or two at the branch base and three or more rows further up. Zooids can be recognized as small rimmed pores, and in well-preserved specimens the apertures are closed by centrally perforated lids. The front of the branches carries small nodes in a row or zigzag line between the apertures. Branches split from time to time giving the colonies a fan-shape or, in the genus Archimedes, create an mesh in the shape of an Archimedes screw.

Fenestella is a genus of bryozoans or moss animals, forming fan–shaped colonies with a netted appearance. It is known from the Middle Ordovician to the early Upper Triassic (Carnian), reaching its largest diversity during the Carboniferous. Many hundreds of species have been described from marine sediments all over the world.

Tabulipora is an extinct genus of bryozoan belonging to the order Trepostomida. It has been found in beds of Permian age in North America, Spitzbergen, South America, and Asia. Specimens typically form cylindrical branching colonies.

Laxifenestella is an extinct genus of bryozoans of the family Fenestellidae, found from the Devonian period to the Permian 412.3 to 254.0 million years ago. The genus colonies consist of a mesh of mostly straight branches in a fan-like or funnel-like shape. There are several species belonging to the Laxifenestella genus being L. borealis, L. texana, L. contracta, L. exserta, L. firma, L. morozova, L. lahuseni, L. oviferorsa, L. sarytshevae, L. stuchugorensis and L. stuckenbergi. Parent taxon of this genus is Fenestellidae with siste taxons being Alternifenestella, Minilya, Spinofenestella. Fossils of the laxifenestella genus in the permian period are found in Australia, Canada, Iran, Omen, Pakistan, and Russia. Fossils from the Carboniferous period are found in spain with Devonian period fossils being found in the Czech Republic. In total there are 22 fossils belonging to the Laxifenestella genus.