Morphology

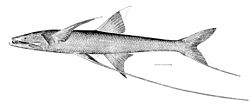

B. grallator is the largest member of its genus, [2] commonly exceeding a standard length of 30 cm (12 in) [1] and reaching total lengths of up to 43.4 cm (17.1 in). [3] It is mostly silver or white in color, with darker coloration around its head and gills and a stripe down each side of its body, mirroring the position of a lateral line. Most notably, it has greatly extended fin rays on the lower lobe of its caudal fin and both of its pelvic fins. When feeding, it is often seen standing on the seafloor using these extensions, in a distinctive "tripod" configuration that gives the species its name. These extensions have been observed to be flexible when swimming but stiff when resting, [4] and it is suggested that fluids are pumped into these fins when the fish is standing to make them more rigid. [5] These fin modifications contain no sensory cells and they likely have no further purpose other than supporting the fish as it stands.

Compared to other members of its genus, B. grallator's pectoral fins are relatively small, and it holds them slightly backwards from its body rather than forward into the current. [6] However, its pectoral and caudal fin extensions are very long, reaching up to a meter in length (approximately three times the length of its body). [2] B. grallator notably lacks an adipose fin, a feature found in most other bathypterois species. It is likely to be slightly negatively buoyant to prevent it from drifting while feeding. [4]

Movement

B. grallator is a subcarangiform swimmer, using a combination of its fins, bananatail, and body to move. Because its adaptations are almost entirely tailored to sitting still, B. grallator's movements are exaggerated and inefficient, and it is an overall poor swimmer. Its style of locomotion alternates between swimming and resting on the seafloor using its fins, using a unique bathypteroiform style of movement that is unique to the genus. When swimming, its pectoral, dorsal, and anal fins are held directly away from the body and are used for stabilization, while its elongated pelvic fins are held directly downward and perpendicular to its body. [6]

When it descends to the seafloor, the tripod fish lifts its caudal fin extension horizontally behind it before touching down on the substrate, and lands on its pelvic fins first. Afterwards, it lowers its caudal fin, which possibly allows the fish to adjust its orientation and body angle relative to the water column. Like other tripod fish, it uses muscle tension on its tendon to move the fin rays, [7] however, independent movement of the caudal fin ray has only been observed in B. grallator. [6]