This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations .(August 2024) |

| Battle of the Tanais River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Hunnic Empire | Alans | ||||||

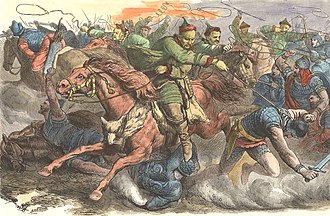

The Battle of the Tanais River in 373 AD between the Huns and the Alans, was fought on the traditional border between Asia and Europe. The Huns were victorious.

Contents

Many Alanian villages and towns near the Terek and Kuban rivers were destroyed by the Huns. [1] Some historians credit this battle as the beginning of the process of Germanic migration, in which the Huns pushed Germanic tribes into central and northern Europe, resulting in many conflicts between those tribes and the Roman Empire. On the banks of the Tanais, the military efforts of the Huns and Alans met with equal valor, but with uneven success. King of Alans was killed. [2]

It was followed by a joint Hun-Alan invasion of the Gothic kingdom of Ermanaric.