Related Research Articles

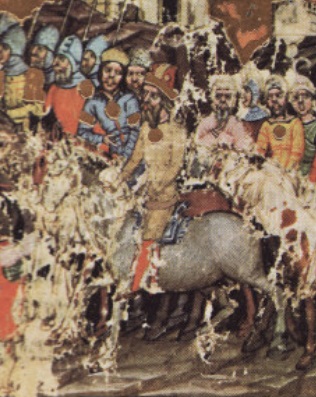

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part of Scythia at the time. By 370 AD, the Huns had arrived on the Volga, causing the westwards movement of Goths and Alans. By 430, they had established a vast, but short-lived, empire on the Danubian frontier of the Roman empire in Europe. Either under Hunnic hegemony, or fleeing from it, several central and eastern European peoples established kingdoms in the region, including not only Goths and Alans, but also Vandals, Gepids, Heruli, Suebians and Rugians.

Odoacer, also spelled Odovacer or Odovacar, was a barbarian soldier and statesman from the Middle Danube who deposed the Western Roman child emperor Romulus Augustulus and became the ruler of Italy (476–493). Odoacer's overthrow of Romulus Augustulus is traditionally understood as marking the end of the Western Roman Empire.

The Hunnic language, or Hunnish, was the language spoken by Huns in the Hunnic Empire, a heterogeneous, multi-ethnic tribal confederation which invaded Eastern and Central Europe, and ruled most of Pannonian Eastern Europe, during the 4th and 5th centuries CE. A variety of languages were spoken within the Hun Empire. A contemporary report by Priscus has that Hunnish was spoken alongside Gothic and the languages of other tribes subjugated by the Huns.

The Sciri, or Scirians, were a Germanic people. They are believed to have spoken an East Germanic language. Their name probably means "the pure ones".

Mundzuk was a Hunnic chieftain, brother of the Hunnic rulers Octar and Rugila, and father of Bleda and Attila by an unknown consort. Jordanes in Getica recounts "For this Attila was the son of Mundzucus, whose brothers were Octar and Ruas, who were supposed to have been kings before Attila, although not altogether of the same [territories] as he".

Ernak was the last known ruler of the Huns, and the third son of Attila. After Attila's death in AD 453, his Empire crumbled and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He succeeded his older brother Ellac in AD 454, and probably ruled simultaneously over Huns in dual kingship with his brother Dengizich, but in separate divisions in separate lands.

Dengizich, was a Hunnic ruler and son of Attila. After Attila's death in 453 AD, his empire crumbled and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He succeeded his older brother Ellac in 454 AD, and probably ruled simultaneously over the Huns in dual kingship with his brother Ernak, but separate divisions in separate lands.

Ardaric was the king of the Gepids, a Germanic tribe closely related to the Goths. He was "famed for his loyalty and wisdom," one of the most trusted adherents of Attila the Hun, who "prized him above all the other chieftains." Ardaric is first mentioned by Jordanes as Attila's most prized vassal at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (451):

Uldin, also spelled Huldin is the first ruler of the Huns whose historicity is undisputed.

Ellac was the oldest son of Attila (434–453) and Kreka. After Attila's death in 453 AD, his empire crumbled, and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He ruled briefly and died at the Battle of Nedao in 454 AD. Ellac was succeeded by his brothers, Dengizich and Ernak.

Octar or Ouptaros was a Hunnic ruler. He ruled in dual kingship with his brother Rugila, possibly with a geographical division, ruling the Western Huns while his brother ruled the Eastern Huns.

By the name Edeko are considered three contemporaneous historical figures, whom many scholars identify as one:

Balamber was ostensibly a chieftain of the Huns, mentioned by Jordanes in his Getica. Jordanes simply called him "king of the Huns" and writes the story of Balamber crushing the tribes of the Ostrogoths in the 370s; somewhere between 370 and more probably 376 AD.

Thurisind was king of the Gepids, an East Germanic Gothic people, from c. 548 to 560. He was the penultimate Gepid king, and succeeded King Elemund by staging a coup d'état and forcing the king's son into exile. Thurisind's kingdom, known as Gepidia, was located in Central Europe and had its centre in Sirmium, a former Roman city on the Sava River.

Boz was the king of the Antes, an early Slavic people that lived in parts of present-day Ukraine. His story is mentioned by Jordanes in the Getica (550–551); in the preceding years, the Ostrogoths under Ermanaric had conquered a large number of tribes in Central Europe, including the Antes. Some years after the Ostrogothic defeat by the invading Huns, a king named Vinitharius, Ermanaric's great-nephew, marched against the Antes of Boz and defeated them. Vinitharius condemned Boz, his sons, and seventy of his nobles, to crucifixion, in order to terrorize the Antes. These conflicts constitute the only pre-6th century contacts between Germanics and Slavs documented in written sources.

Laudaricus was a prominent Hunnic chieftain and general active in the first half of the 5th century.

The history of the Huns spans the time from before their first secure recorded appearance in Europe around 370 AD to after the disintegration of their empire around 469. The Huns likely entered Western Asia shortly before 370, from Central Asia: they first conquered the Goths and the Alans, pushing a number of tribes to seek refuge within the Roman Empire. In the following years, the Huns conquered most of the Germanic and Scythian tribes outside of the borders of the Roman Empire. They also launched invasions of both the Asian provinces of Rome and the Sasanian Empire in 375. Under Uldin, the first Hunnic ruler named in contemporary sources, the Huns launched a first unsuccessful large-scale raid into the Eastern Roman Empire in Europe in 408. From the 420s, the Huns were led by the brothers Octar and Ruga, who both cooperated with and threatened the Romans. Upon Ruga's death in 435, his nephews Bleda and Attila became the new rulers of the Huns, and launched a successful raid into the Eastern Roman Empire before making peace and securing an annual tribute and trading raids under the Treaty of Margus. Attila appears to have killed his brother, and became sole ruler of the Huns in 445. He would go on to rule for the next eight years, launching a devastating raid on the Eastern Roman Empire in 447, followed by an invasion of Gaul in 451. Attila is traditionally held to have been defeated in Gaul at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, however some scholars hold the battle to have been a draw or Hunnic victory. The following year, the Huns invaded Italy and encountered no serious resistance before turning back.

Basich or Basikh was a Hun military commander who co-led an invasion of Persia in 395 AD together with Kursich.

Kursich was a Hun general and royal family member. He led a Hunnish army in the Hunnic invasion of Persia in 395 AD.

Mauricius was a Gepid general fighting for the Byzantine Empire. He was the son of Magister militium Mundus. He was presumably an MVM vacans.

References

- 1 2 Krautschik 2010, p. 763.

- 1 2 3 Tinnefeld 2006.

- ↑ Doerfer 1973, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Pritsak 1982, pp. 438–439, 453.

- ↑ Karlgren 1957, p. 53.

- ↑ Zheng Zhang (Chinese: 鄭張), Shang-fang (Chinese: 尚芳). 璊. ytenx.org [韻典網] (in Chinese). Rearranged by BYVoid.

- ↑ Karlgren 1957, p. 68.

- ↑ Zheng Zhang (Chinese: 鄭張), Shang-fang (Chinese: 尚芳). 珠. ytenx.org [韻典網] (in Chinese). Rearranged by BYVoid

- ↑ Pritsak 1982, p. 439, 453.

- ↑ Pritsak 1982, p. 449–453.

- ↑ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 409.

- ↑ Schönfeld 1911, p. 169.

- ↑ Förstemann 1900, p. 1133.

- 1 2 Krautschik 1989, p. 119.

- ↑ Schramm 2013, p. 179.

- ↑ Schütte 1933, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 4 Amory 1997, p. 398.

- ↑ Croke 1982, p. 130.

- ↑ Theophanes, 6032

- 1 2 Krautschik 2010, p. 764.

- ↑ Wozniak, Frank (January 1, 1979). "Byzantine Diplomacy and the Lombard-Gepidic Wars". Balkan Studies. 20 (1): 141 – via OJS / PKP.

- 1 2 3 4 Amory 1997, p. 397.

- ↑ Krautschik 2010, pp. 764–765.

- 1 2 Krautschik 2010, p. 397.

- ↑ Amory 1997, pp. 397–398.