Glassblowing is a glassforming technique that involves inflating molten glass into a bubble with the aid of a blowpipe. A person who blows glass is called a glassblower, glassmith, or gaffer. A lampworker manipulates glass with the use of a torch on a smaller scale, such as in producing precision laboratory glassware out of borosilicate glass.

Daphni or Dafni is an eleventh-century Byzantine monastery eleven kilometers northwest of central Athens in the suburb of Chaidari, south of Athinon Avenue (GR-8A). It is situated near the forest of the same name, on the Sacred Way that led to Eleusis. The forest covers about 18 km2 (7 sq mi), and surrounds a laurel grove. "Daphni" is the modern Greek name that means "laurel grove", derived from Daphneion (Lauretum).

Marianne Brandt was a German painter, sculptor, photographer, metalsmith, and designer who studied at the Bauhaus art school in Weimar and later became head of the Bauhaus Metall-Werkstatt in Dessau in 1928. Today, Brandt's designs for household objects such as lamps and ashtrays are considered timeless examples of modern industrial design. She also created photomontages.

The Eretz Israel Museum is a historical and archeological museum in the Ramat Aviv neighborhood of Tel Aviv, Israel.

Koloman Moser was an Austrian artist who exerted considerable influence on twentieth-century graphic art. He was one of the foremost artists of the Vienna Secession movement and a co-founder of Wiener Werkstätte.

A conchylia cup is a Roman cup type with a conical base and a slightly everted rim, made of transparent to slightly colored glass. Its distinguishing characteristics are stylized open mouthed fish with indented fins and curving tails, often made of translucent glass and applied wavy colored threads, and affixed to the outer surface of the cup to produce its three-dimensional aspect. The most common type appears to have stylized fish swimming to the left. These vases could be entirely free-blown or their cup shape mold-blown, and the fish, or other sea creatures, free-blown onto it.

The Lycurgus Cup is a 4th-century Roman glass cage cup made of a dichroic glass, which shows a different colour depending on whether or not light is passing through it: red when lit from behind and green when lit from in front. It is the only complete Roman glass object made from this type of glass, and the one exhibiting the most impressive change in colour; it has been described as "the most spectacular glass of the period, fittingly decorated, which we know to have existed".

Roman glass objects have been recovered across the Roman Empire in domestic, industrial and funerary contexts. Glass was used primarily for the production of vessels, although mosaic tiles and window glass were also produced. Roman glass production developed from Hellenistic technical traditions, initially concentrating on the production of intensely coloured cast glass vessels. However, during the 1st century AD the industry underwent rapid technical growth that saw the introduction of glass blowing and the dominance of colourless or 'aqua' glasses. Production of raw glass was undertaken in geographically separate locations to the working of glass into finished vessels, and by the end of the 1st century AD large scale manufacturing resulted in the establishment of glass as a commonly available material in the Roman world, and one which also had technically very difficult specialized types of luxury glass, which must have been very expensive.

The Museum of Byzantine Culture is a museum in Thessaloniki, Central Macedonia, Greece, which opened in 1994.

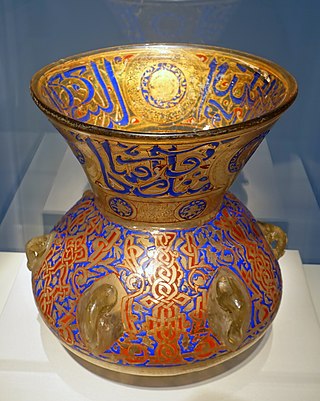

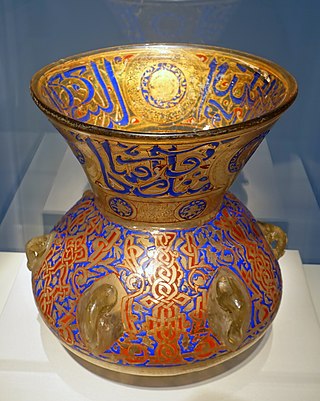

The influence of the Islamic world to the history of glass is reflected by its distribution around the world, from Europe to China, and from Russia to East Africa. Islamic glass developed a unique expression that was characterized by the introduction of new techniques and the reinterpreting of old traditions.

Sasanian Glass is the glassware produced between the 3rd and the 7th centuries AD within the limits of the Sasanian Empire of Persia, namely present-day Northern Iraq, Iran and Central Asia. This is a silica-soda-lime glass production characterized by thick glass-blown vessels relatively sober in decoration, avoiding plain colours in favour of transparency and with vessels worked in one piece without over- elaborate amendments. Thus the decoration usually consists of solid and visual motifs from the mould (reliefs), with ribbed and deeply cut facets, although other techniques like trailing and applied motifs were practised.

Early American molded glass refers to glass functional and decorative objects, such as bottles and dishware, that were manufactured in the United States in the 19th century. The objects were produced by blowing molten glass into a mold, thereby causing the glass to assume the shape and pattern design of the mold. When a plunger rather than blowing is used, as became usual later, the glass is technically called pressed glass. Common blown molded tableware items bearing designs include salt dishes, sugar bowls, creamers, celery stands, decanters, and drinking glasses.

Liz James is a British art historian who studies the art of the Byzantine Empire. She is Professor of the History of Art at the University of Sussex.

Tarsus Museum is an archaeology and ethnography museum in Tarsus, Mersin Province, in southern Turkey.

The Lampsacus Treasure or Lapseki Treasure is the name of an important early Byzantine silver hoard found near the town of Lapseki in modern-day Turkey. Most of the hoard is now in the British Museum's collection, although a few items can be found in museums in Paris and Istanbul too.

Byzantine units of measurement were a combination and modification of the ancient Greek and Roman units of measurement used in the Byzantine Empire.

Amasya Museum, also known as Archaeological Museum of Amasya, is a national museum in Amasya, northern Turkey, exhibiting archaeological artifacts found in and around the city as well as ethnographic items related to the region's history of cultural life. Established in 1958, the museum owns nearly twenty-four thousand items for exhibition belonging to eleven historic civilizations.

Silver was important in Byzantine art and society more broadly as it was the most precious metal right after gold. Byzantine silver was prized in official, religious, and domestic realms. Aristocratic homes had silver dining ware, and in churches silver was used for crosses, liturgical vessels such as the patens and chalices required for every Eucharist. The imperial offices periodically issued silver coinage and regulated the use of silver through control stamps. About 1,500 silver plates and crosses survive from the Byzantine era.

Art Nouveau glass is fine glass in the Art Nouveau style. Typically the forms are undulating, sinuous and colorful art, usually inspired by natural forms. Pieces are generally larger than drinking glasses, and decorative rather than practical, other than for use as vases and lighting fittings; there is little tableware. Prominently makers, from the 1890s onwards, are in France René Lalique, Emile Gallé and the Daum brothers, the American Louis Comfort Tiffany, Christopher Dresser in Scotland and England, and Friedrich Zitzman, Karl Koepping and Max Ritter von Spaun in Germany. Art Nouveau glass included decorative objects, vases, lamps, and stained glass windows. It was usually made by hand, and was usually colored with metal oxides while in a molten state in a furnace.

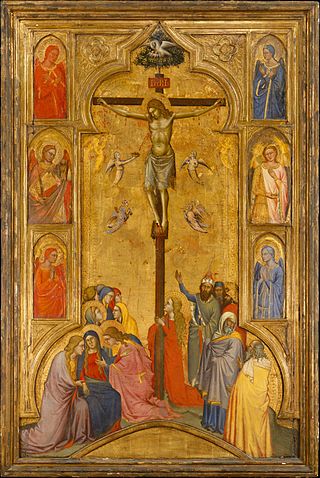

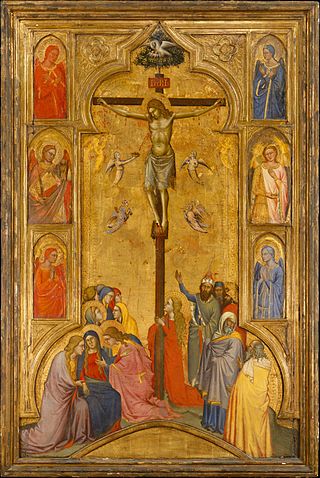

Gold ground or gold-ground (adjective) is a term in art history for a style of images with all or most of the background in a solid gold colour. Historically, real gold leaf has normally been used, giving a luxurious appearance. The style has been used in several periods and places, but is especially associated with Byzantine and medieval art in mosaic, illuminated manuscripts and panel paintings, where it was for many centuries the dominant style for some types of images, such as icons. For three-dimensional objects, the term is gilded or gold-plated.