Related Research Articles

Byzantium or Byzantion was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name Byzantion and its Latinization Byzantium continued to be used as a name of Constantinople sporadically and to varying degrees during the thousand-year existence of the Eastern Roman Empire, which was commonly referred to by the former name of that city, the Byzantine Empire. Byzantium was colonized by Greeks from Megara in the 7th century BC and remained primarily Greek-speaking until its conquest by the Ottoman Empire in AD 1453.

Constantinople became the capital of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine the Great in 330. Following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century, Constantinople remained the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, the Latin Empire (1204–1261), and the Ottoman Empire (1453–1922). Following the Turkish War of Independence, the Turkish capital then moved to Ankara. Officially renamed Istanbul in 1930, the city is today the largest city in Europe, straddling the Bosporus strait and lying in both Europe and Asia, and the financial centre of Turkey.

Manuel II Palaiologos or Palaeologus was Byzantine emperor from 1391 to 1425. Shortly before his death he was tonsured a monk and received the name Matthew. His wife Helena Dragaš saw to it that their sons, John VIII and Constantine XI, became emperors. He is commemorated by the Greek Orthodox Church on July 21.

Photios I, also spelled Photius, was the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople from 858 to 867 and from 877 to 886. He is recognized in the Eastern Orthodox Church as Saint Photios the Great.

ManuelChrysoloras was a Byzantine Greek classical scholar, humanist, philosopher, professor, and translator of ancient Greek texts during the Renaissance. Serving as the ambassador for the Byzantine emperor Manuel II Palaiologos in medieval Italy, he became a renowned teacher of Greek literature and history in the republics of Florence and Venice, and today he's widely regarded as a pioneer in the introduction of ancient Greek literature to Western Europe during the Late Middle Ages.

The Empire of Nicaea or the Nicene Empire was the largest of the three Byzantine Greek rump states founded by the aristocracy of the Byzantine Empire that fled when Constantinople was occupied by Western European and Venetian armed forces during the Fourth Crusade, a military event known as the Sack of Constantinople. Like the other Byzantine rump states that formed due to the 1204 fracturing of the empire, such as the Empire of Trebizond and the Despotate of Epirus, it was a continuation of the eastern half of the Roman Empire that survived well into the medieval period. A fourth state, known in historiography as the Latin Empire, was established by an army of Crusaders and the Republic of Venice after the capture of Constantinople and the surrounding environs.

The Byzantine navy was the naval force of the Byzantine Empire. Like the state it served, it was a direct continuation from its Roman predecessor, but played a far greater role in the defence and survival of the state than its earlier iteration. While the fleets of the Roman Empire faced few great naval threats, operating as a policing force vastly inferior in power and prestige to the army, command of the sea became vital to the very existence of the Byzantine state, which several historians have called a "maritime empire".

The Imperial University of Constantinople, sometimes known as the University of the Palace Hall of Magnaura, was an Eastern Roman educational institution that could trace its corporate origins to 425 AD, when the emperor Theodosius II founded the Pandidacterium.

The Bibliotheca or Myriobiblos was a ninth-century work of Byzantine Patriarch of Constantinople Photius, dedicated to his brother and composed of 279 reviews of books which he had read.

The Byzantine Greeks were the Greek-speaking Eastern Romans throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. They were the main inhabitants of the lands of the Byzantine Empire, of Constantinople and Asia Minor, the Greek islands, Cyprus, and portions of the southern Balkans, and formed large minorities, or pluralities, in the coastal urban centres of the Levant and northern Egypt. Throughout their history, the Byzantine Greeks self-identified as Romans, but are referred to as "Byzantine Greeks" in modern historiography. Latin speakers identified them simply as Greeks or with the term Romaei.

Despot or despotes was a senior Byzantine court title that was bestowed on the sons or sons-in-law of reigning emperors, and initially denoted the heir-apparent of the Byzantine emperor.

Giacomo or Jacopo d'Angelo, also surnamed De Scarperia,, better known by his Latin name Jacobus Angelus, was an Italian classical scholar, humanist, and translator of ancient Greek texts during the Renaissance. Named for the village of Scarperia in the Mugello in the Republic of Florence, he traveled to Venice where the Byzantine emperor Manuel II Palaiologos' ambassador Manuel Chrysoloras was teaching Greek, the first scholar to hold such course in medieval Italy.

The migration waves of Byzantine Greek scholars and émigrés in the period following the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 is considered by many scholars key to the revival of Greek studies that led to the development of the Renaissance humanism and science. These émigrés brought to Western Europe the relatively well-preserved remnants and accumulated knowledge of their own (Greek) civilization, which had mostly not survived the Early Middle Ages in the West. The Encyclopædia Britannica claims: "Many modern scholars also agree that the exodus of Greeks to Italy as a result of this event marked the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance", although few scholars date the start of the Italian Renaissance this late.

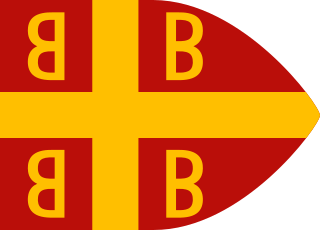

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred in Constantinople during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the fall of the West in the 5th century AD, and continued to exist until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. During most of its existence, the empire remained the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in the Mediterranean world. The term "Byzantine Empire" was only coined following the empire's demise; its citizens referred to the polity as the "Roman Empire" and to themselves as "Romans". Due to the imperial seat's move from Rome to Byzantium, the adoption of state Christianity, and the predominance of Greek instead of Latin, modern historians continue to make a distinction between the earlier Roman Empire and the later Byzantine Empire.

Byzantine rhetoric refers to rhetorical theorizing and production during the time of the Byzantine Empire. Byzantine rhetoric is significant in part because of the sheer volume of rhetorical works produced during this period. Rhetoric was the most important and difficult topic studied in the Byzantine education system, beginning at the Pandidakterion in early fifth century Constantinople, where the school emphasized the study of rhetoric with eight teaching chairs, five in Greek and three in Latin. The hard training of Byzantine rhetoric provided skills and credentials for citizens to attain public office in the imperial service, or posts of authority within the Church.

The mesazon was a high dignitary and official during the last centuries of the Byzantine Empire, who acted as the chief minister and principal aide of the Byzantine emperor. In the West, the dignity was understood as being that of the imperial chancellor.

The Karabisianoi, sometimes anglicized as the Carabisians, were the main forces of the Byzantine navy from the mid-seventh until the early eighth centuries. The name derives from a term for ships, and means "people of the ships". The Karabisianoi were the first new and permanent naval establishment of the Byzantine Empire, formed to confront the early Muslim conquests at sea. They were disbanded and replaced with a series of maritime themes sometime in 718–730.

In the year before the Council of Constantinople in 381, the Trinitarian version of Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians as the Roman Empire's state religion. Historians refer to the Nicene church associated with emperors in a variety of ways: as the catholic church, the orthodox church, the imperial church, the Roman church, or the Byzantine church, although some of those terms are also used for wider communions extending outside the Roman Empire. The Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Catholic Church all claim to stand in continuity from the Nicene church to which Theodosius granted recognition.

The law school of Berytus was a center for the study of Roman law in classical antiquity located in Berytus. It flourished under the patronage of the Roman emperors and functioned as the Roman Empire's preeminent center of jurisprudence until its destruction in AD 551.

Hellenisation in the Byzantine Empire describes the spread and intensification of ancient Greek culture, religion and language in the Roman Empire and which forms the basis of modern historians calling this later period the Byzantine Empire. The theory of Hellenisation generally applies to the influence of foreign cultures subject to Greek influence or occupation, which includes the ethnic and cultural homogenisation which took place throughout the life of the Byzantine Empire (330-1453).

References

Primary sources

- IMPERATORIS THEODOSII CODEX (in Latin). Constantinopolis.

Secondary sources

- Browning, Robert: "Universities, Byzantine", in: Dictionary of the Middle Ages , Vol. 12, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1989, pp. 300–302

- Browning, Robert (1962), "The patriarchal school at Constantinople in the twelfth century", Byzantion, 32: 167–202

- Wilson, N. G. (1983), Scholars of Byzantium, London: Duckworth, ISBN 0-7156-1705-2