Body odor or body odour (BO) is present in all animals and its intensity can be influenced by many factors. Body odor has a strong genetic basis, but can also be strongly influenced by various factors, such as sex, diet, health, and medication. The body odor of human males plays an important role in human sexual attraction, as a powerful indicator of MHC/HLA heterozygosity. Significant evidence suggests that women are attracted to men whose body odor is different from theirs, indicating that they have immune genes that are different from their own, which may produce healthier offspring.

A detection dog or sniffer dog is a dog that is trained to use its senses to detect substances such as explosives, illegal drugs, wildlife scat, currency, blood, and contraband electronics such as illicit mobile phones. The sense most used by detection dogs is smell. Hunting dogs that search for game, and search and rescue dogs that work to find missing humans are generally not considered detection dogs but fit instead under their own categories. There is some overlap, as in the case of cadaver dogs, trained to search for human remains.

Trimethylaminuria (TMAU), also known as fish odor syndrome or fish malodor syndrome, is a rare metabolic disorder that causes a defect in the normal production of an enzyme named flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3). When FMO3 is not working correctly or if not enough enzyme is produced, the body loses the ability to properly convert the fishy-smelling chemical trimethylamine (TMA) from precursor compounds in food digestion into trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), through a process called N-oxidation.

Tracking refers to a dog's ability to detect, recognize and follow a specific scent. Possessing heightened olfactory abilities, dogs, especially scent hounds, are able to detect, track and locate the source of certain odours. A deeper understanding of the physiological mechanisms and the phases involved in canine scent tracking has allowed humans to utilize this animal behaviour in a variety of professions. Through domestication and the human application of dog behaviour, different methods and influential factors on tracking ability have been discovered. While tracking was once considered a predatory technique of dogs in the wild, it has now become widely used by humans.

A working animal is an animal, usually domesticated, that is kept by humans and trained to perform tasks instead of being slaughtered to harvest animal products. Some are used for their physical strength or for transportation, while others are service animals trained to execute certain specialized tasks. They may also be used for milking or herding. Some, at the end of their working lives, may also be used for meat or leather.

The sentinel lymph node is the hypothetical first lymph node or group of nodes draining a cancer. In case of established cancerous dissemination it is postulated that the sentinel lymph nodes are the target organs primarily reached by metastasizing cancer cells from the tumor.

A search-and-rescue (SAR) dog is a dog trained to respond to crime scenes, accidents, missing persons events, as well as natural or man-made disasters. These dogs detect human scent, which is a distinct odor of skin flakes and water and oil secretions unique to each person and have been known to find people under water, snow, and collapsed buildings, as well as remains buried underground. SAR dogs are a non-invasive aid in the location of humans, alive or deceased.

Explosive detection is a non-destructive inspection process to determine whether a container contains explosive material. Explosive detection is commonly used at airports, ports and for border control.

Integrative Cancer Therapies is a peer-reviewed medical journal focusing on complementary and alternative and integrative medicine in the care for and treatment of patients with cancer. Therapies like diets and lifestyle modifications, as well as experimental vaccines and chemotherapy are the subject of this journal. It was established in 2002 and is published by SAGE Publications. The editor-in-chief is Keith I. Block.

An electronic nose is an electronic sensing device intended to detect odors or flavors. The expression "electronic sensing" refers to the capability of reproducing human senses using sensor arrays and pattern recognition systems.

An odor or odour is caused by one or more volatilized chemical compounds that are generally found in low concentrations that humans and many animals can perceive via their sense of smell. An odor is also called a "smell" or a "scent", which can refer to either an unpleasant or a pleasant odor.

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

A diabetic alert dog is an assistance dog trained to detect high (hyperglycemia) or low (hypoglycemia) levels of blood sugar in humans with diabetes and alert their owners to dangerous changes in blood glucose levels. This allows their owners to take steps to return their blood sugar to normal, such as using glucose tablets, sugar, and carbohydrate-rich food. The dog can prompt a human to take insulin.

Breath gas analysis is a method for gaining information on the clinical state of an individual by monitoring volatile organic compounds (VOCs) present in the exhaled breath. Exhaled breath is naturally produced by the human body through expiration and therefore can be collected in non-invasively and in an unlimited way. VOCs in exhaled breath can represent biomarkers for certain pathologies. Breath gas concentration can then be related to blood concentrations via mathematical modeling as for example in blood alcohol testing. There are various techniques that can be employed to collect and analyze exhaled breath. Research on exhaled breath started many years ago, there is currently limited clinical application of it for disease diagnosis. However, this might change in the near future as currently large implementation studies are starting globally.

Sniffer bees or sniffer wasps are insects in the order Hymenoptera that can be trained to perform a variety of tasks to detect substances such as explosive materials or illegal drugs, as well as some human and plant diseases. The sensitivity of the olfactory senses of bees and wasps in particular have been shown to rival the abilities of sniffer dogs, though they can only be trained to detect a single scent each.

The dog sense of smell is the most powerful sense of this species, the olfactory system of canines being much more complex and developed than that of humans. It is believed to be up to 10 million times as sensitive as a human's in specialized breeds. Dogs have roughly forty times more smell-sensitive receptors than humans, ranging from about 125 million to nearly 300 million in some dog breeds, such as bloodhounds. These receptors are spread over an area about the size of a pocket handkerchief. Dogs' sense of smell also includes the use of the vomeronasal organ, which is used primarily for social interactions.

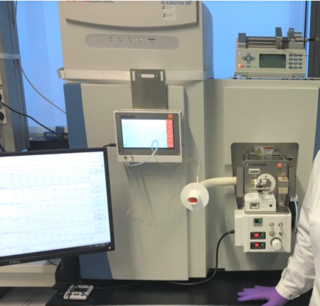

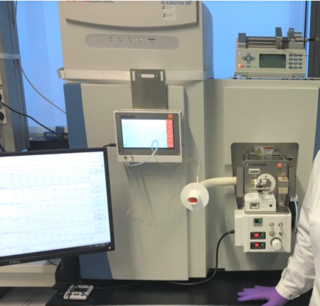

Secondary electro-spray ionization (SESI) is an ambient ionization technique for the analysis of trace concentrations of vapors, where a nano-electrospray produces charging agents that collide with the analyte molecules directly in gas-phase. In the subsequent reaction, the charge is transferred and vapors get ionized, most molecules get protonated and deprotonated. SESI works in combination with mass spectrometry or ion-mobility spectrometry.

Urinary cell-free DNA (ucfDNA) refers to DNA fragments in urine released by urogenital and non-urogenital cells. Shed cells on urogenital tract release high- or low-molecular-weight DNA fragments via apoptosis and necrosis, while circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) that passes through glomerular pores contributes to low-molecular-weight DNA. Most of the ucfDNA is low-molecular-weight DNA in the size of 150-250 base pairs. The detection of ucfDNA composition allows the quantification of cfDNA, circulating tumour DNA, and cell-free fetal DNA components. Many commercial kits and devices have been developed for ucfDNA isolation, quantification, and quality assessment.

Smell as evidence of disease has been long used, dating back to Hippocrates around 400 years BCE. It is still employed with a focus on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) found in body odor. VOCs are carbon-based molecular groups having a low molecular weight, secreted during cells' metabolic processes. Their profiles may be altered by diseases such as cancer, metabolic disorders, genetic disorders, infections, and among others. Abnormal changes in VOC composition can be identified through equipment such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry(GC-MS), electronic nose (e-noses), and trained non-human olfaction.

Olfactic communication is a channel of nonverbal communication referring to the various ways people and animals communicate and engage in social interaction through their sense of smell. Our human olfactory sense is one of the most phylogenetically primitive and emotionally intimate of the five senses; the sensation of smell is thought to be the most matured and developed human sense.