Debtor to creditor

A country recovering from a major defeat, Japan remained a net debtor nation until the mid-1960s, although it was never as far in debt as many of the more recently developing countries. By 1967 Japanese investments overseas had begun to exceed foreign investments in Japan, changing Japan from a net debtor to a net creditor nation. The country remained a modest net creditor until the 1980s, when its creditor position expanded explosively, altering Japan's relationship to the rest of the world. [1]

In Japan's balance of payments data, these changes are most readily seen in the long-term capital account. During the first half of the 1960s, this account generally showed small net inflows of capital (as did the short-term capital account). From 1965 on, the long-term capital account consistently showed an outflow, ranging from US$1 billion to US$12 billion during the 1970s. The sharp shift in the balance of payments brought about by the oil price hike at the decade's end produced an unusual net inflow of long-term capital in 1980 of US$2.3 billion, but thereafter the outflow resumed and grew enormously. From nearly US$10 billion in 1981, the annual net outflow of long-term capital reached nearly US$137 billion in 1987 and then dropped slightly, to just over US$130 billion, in 1988. [1]

Short-term capital flows in the balance of payments do not show so clear a picture. These more volatile flows have generally added to the net capital outflow, but in some years movements in international differentials in interest rates or other factors led to a net inflow of short-term capital. [1]

The other significant part of capital flows in the balance of payments is the movement in gold and foreign-exchange reserves held by the government, which represent the funds held by the Bank of Japan to intervene in foreign-exchange markets to affect the value of the yen. In the 1970s, the size of these markets became so large that any government intervention was only a small share of total transactions, but Japan and other governments used their reserves to influence exchange rates when necessary. In the second half of the 1970s, for example, foreign-exchange reserves rose rapidly, from a total of US$12.8 billion in 1975 to US$33 billion by 1978, as the Bank of Japan sold yen to buy dollars in foreign-exchange markets to slow or stop the rise in the yen's value, fearful that such a rise would adversely affect Japanese exports. The same operation occurred on a much larger scale after 1985. From US$26.5 billion in 1985 (a level little changed from the decade's beginning), exchange reserves had climbed to almost US$98 billion by 1988 before declining to US$84.8 in 1989 and US$77 billion in 1990. This intervention was similarly inspired by concern about the yen's high value. [1]

The combination of net outflows of long- and short-term capital and rising holdings of foreign exchange by the central government produced an enormous change in Japan's accumulated holdings of foreign assets, compared with foreigners' holdings of assets in Japan. As a result, from a net asset position of US$11.5 billion in 1980 (meaning that Japanese investors held US$11.5 billion more in foreign assets than foreigners held in Japan), Japan's international net assets had grown to more than US$383 billion by 1991. Japanese assets abroad grew from nearly US$160 billion in 1980 to over US$2 trillion by 1991, a more than twelvefold increase. Liabilities—investments by foreigners in Japan—expanded somewhat more slowly, about elevenfold, from US$148 billion in 1980 to US$1.6 trillion in 1991. Dramatic shifts were seen in portfolio securities purchases—stocks and Bonds—in both directions. Japanese purchases of foreign securities went from only US$4.2 billion in 1976 to over US$21 billion in 1980 and to US$632.1 billion by 1991. Although foreign purchases of Japanese securities also expanded, the growth was slower and was approximately US$444 billion in 1988. [1]

Capital flows have been heavily affected by government policy. During the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s, when Japan faced chronic current account deficits, concern over maintaining a high credit rating in international capital markets and fear of having to devalue the currency and of foreign ownership of Japanese companies all led to tight controls over both inflow and outflow of capital. As part of these controls, for example, government severely restricted foreign direct investment in Japan, but it encouraged licensing agreements with foreign firms to obtain access to their technology. As Japan's current account position strengthened in the 1960s, the nation came under increasing pressure to liberalise its tight controls. [1]

When Japan became a member of the OECD in 1966, it agreed to liberalise its capital markets. This process began in 1967 and continues. Decontrol of international capital flows was aided in 1980, when the new Foreign Exchange and Foreign Control Law went into effect. In principle, all external economic transactions were free of control, unless specified otherwise. In practice, a wide range of transactions continued to be subject to some form of formal or informal control by the government. [1]

In an effort to reduce capital controls, negotiations between Japan and the United States were held, producing an agreement in 1984, the Yen-Dollar Accord. This agreement led to additional liberalising measures that were implemented over the next several years. Many of these changes concerned the establishment and functioning of markets for financial instruments in Japan (such as a short-term treasury bill market) rather than the removal of international capital controls per se. This approach was taken because of United States concerns that foreign investment in Japan was impeded by a lack of various financial instruments in the country and by the government's continued control of interest rates for many of those instruments that did exist. As a result of the agreement, interest rates on large bank deposits were decontrolled, and the minimum denomination for certificates of deposit was lowered. [1]

By the end of the 1980s, barriers to capital flow were no longer a major issue in Japan-United States relations. Imbalances in the flows and in accumulated totals of capital investment, with Japan becoming a large world creditor, were emerging as new areas of tension. This tension was exacerbated by the fact that the United States became the world's largest net debtor at the same time that Japan became its largest net creditor. Nevertheless, no policy decisions have been made that would restrict the flow of Japanese capital to the United States. [1]

One important area of capital flows is direct investment—outright ownership or control (as opposed to portfolio investment). Japan's foreign direct investment has grown rapidly, although not as dramatically as its portfolio investment. Data collected by its Ministry of Finance show the accumulated value of Japanese foreign direct investment growing from under US$3.6 billion in 1970 to US$36.5 billion in 1980 and to nearly US$353 billion by 1991. Direct investment tends to be very visible, and the rapid increase of Japan's direct investments in countries such as the United States, combined with the large imbalance between Japan's overseas investment and foreign investment in Japan, was a primary cause of tension at the end of the 1980s. [1]

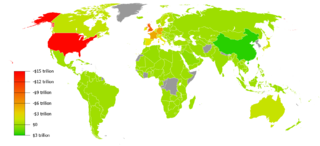

The location of Japan's direct investments abroad has been shifting. In 1970, 21% of its investments were in Asia, and nearly 22% in the United States. By 1991 the share of investments in Asia had dropped to 15%, while that in the United States had risen sharply, to over 42% of the total. During this period, Japan's share of investments decreased in Latin America (from nearly 16% in 1970 to less than 13% in 1988), decreased in Africa (down slightly from 3% to under 2%), and held rather steady in Europe (up slightly from nearly 18% to over 19%). Both the Middle East (down from over 9% to under 1%) and the Pacific (down from roughly 8% to 6%) became relatively less important locations for Japanese investments. However, because of the rapid growth in the dollar amounts of the investments, these shifts were all relative. Even in the Middle East, the dollar value of Japanese investments had grown. [1]

The drive to invest overseas stemmed from several motives. A major reason for many early investments was to obtain access to raw materials. As Japan became more dependent on imported raw materials, energy, and food during the 1960s and 1970s, direct investments were one way of ensuring supply. The Middle East, Australia, and some Asian countries (such as Indonesia) were major locations for such investments by 1970. Second, rising labour costs during the 1960s and 1970s led certain labour-intensive industries, especially textiles, to move abroad. [1]

Investment in other industrial countries, such as the US, was often motivated by barriers to exports from Japan. The restrictions on automobile exports to the US, which went into effect in 1981, became a primary motivation for Japanese automakers to establish assembly plants in the US. The same situation had occurred earlier, in the 1970s, for plants manufacturing television sets. Japanese firms exporting from developing countries often received preferential tariff treatment in developed countries (under the Generalised System of Preferences). In short, protectionism in developed countries often motivated Japanese foreign direct investment. [1]

After 1985, a new and important incentive materialised for such investments. The rapid rise in the value of the yen seriously undermined the international competitiveness of many products manufactured in Japan. While this situation had been true for textiles in the 1960s, after 1985 it also affected a much wider range of more sophisticated products. Japanese manufacturers began seeking lower-cost production bases. This factor, rather than any increase in foreign protectionism, appeared to lie behind the acceleration of overseas investments after 1985. [1]

This cost disadvantage also led more Japanese firms to think of their overseas factories as a source of products for the Japanese market itself. Except for the basic processing of raw materials, manufacturers had previously regarded foreign investments as a substitute for exports rather than as an overseas base for home markets. The share of output from Japanese factories in the lower-wage-cost countries of Asia that was destined for the Japanese market (rather than for local markets or for export) rose from 10% in 1980 to 16% in 1987, but had returned to 11.8% in 1990. [1]