Capital punishment, also called the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as a punishment for a crime. It has historically been used in almost every part of the world. Since the mid-19th century many countries have abolished or discontinued the practice. In 2022, the 5 countries that executed the most people were, in descending order, China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United States.

Capital punishment in the United Kingdom predates the formation of the UK, having been used within the British Isles from ancient times until the second half of the 20th century. The last executions in the United Kingdom were by hanging, and took place in 1964; capital punishment for murder was suspended in 1965 and finally abolished in 1969. Although unused, the death penalty remained a legally defined punishment for certain offences such as treason until it was completely abolished in 1998; the last execution for treason took place in 1946. In 2004, Protocol No. 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights became binding on the United Kingdom; it prohibits the restoration of the death penalty as long as the UK is a party to the convention.

The U.S. state of Washington enforced capital punishment until the state's capital punishment statute was declared null and void and abolished in practice by a state Supreme Court ruling on October 11, 2018. The court ruled that it was unconstitutional as applied due to racial bias however it did not render the wider institution of capital punishment unconstitutional and rather required the statute to be amended to eliminate racial biases. From 1904 to 2010, 78 people were executed by the state; the last was Cal Coburn Brown on September 10, 2010. In April 2023, Governor Jay Inslee signed SB5087 which formally abolished capital punishment in Washington State and removed provisions for capital punishment from state law.

Capital punishment in France is banned by Article 66-1 of the Constitution of the French Republic, voted as a constitutional amendment by the Congress of the French Parliament on 19 February 2007 and simply stating "No one can be sentenced to the death penalty". The death penalty was already declared illegal on 9 October 1981 when President François Mitterrand signed a law prohibiting the judicial system from using it and commuting the sentences of the seven people on death row to life imprisonment. The last execution took place by guillotine, being the main legal method since the French Revolution; Hamida Djandoubi, a Tunisian citizen convicted of torture and murder on French soil, was put to death in September 1977 in Marseille.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Japan. In practice, it is applied only for aggravated murder, but the current Penal Code and several laws list 14 capital crimes, including conspiracy to commit civil war; conspiracy with a foreign power to provoke war against Japan; murder; obstruction of the operation of railroads, ships, or airplanes resulting in the death of the victim; poisoning of the water supply resulting in the death of the victim; intentional flooding; use of a bomb; and arson of a dwelling; all resulting in the death of the victim. Executions are carried out by long drop hanging, and take place at one of the seven execution chambers located in major cities across the country.

Capital punishment in Sweden was last used in 1910, though it remained a legal sentence for at least some crimes until 1973. It is now outlawed by the Swedish Constitution, which states that capital punishment, corporal punishment, and torture are strictly prohibited. At the time of the abolition of the death penalty in Sweden, the legal method of execution was beheading. It was one of the last states in Europe to abolish the death penalty.

Capital punishment is forbidden in Switzerland under article 10, paragraph 1 of the Swiss Federal Constitution. Capital punishment was abolished from federal criminal law in 1942, but remained available in military criminal law until 1992. The last actual executions in Switzerland took place during World War II.

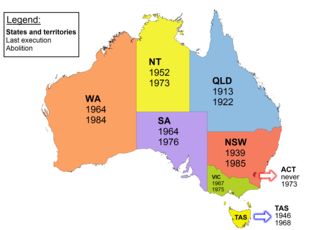

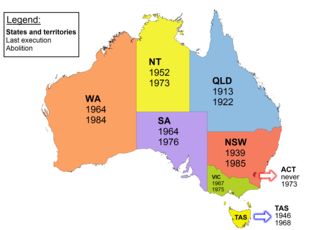

Capital punishment in Australia has been abolished in all jurisdictions since 1985. Queensland abolished the death penalty in 1922. Tasmania did the same in 1968. The Commonwealth abolished the death penalty in 1973, with application also in the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. Victoria did so in 1975, South Australia in 1976, and Western Australia in 1984. New South Wales abolished the death penalty for murder in 1955, and for all crimes in 1985. In 2010, the Commonwealth Parliament passed legislation prohibiting the re-establishment of capital punishment by any state or territory. Australian law prohibits the extradition or deportation of a prisoner to another jurisdiction if they could be sentenced to death for any crime.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Malaysian law.

Capital punishment in the Republic of Ireland was abolished in statute law in 1990, having been abolished in 1964 for most offences including ordinary murder. The last person to be executed by the British state on the island of Ireland was Robert McGladdery, who was hanged on 20 December 1961 in Crumlin Road Gaol in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The last person to be executed by the state in the Republic of Ireland was Michael Manning, hanged for murder on 20 April 1954. All subsequent death sentences in the Republic of Ireland, the last handed down in 1985, were commuted by the President, on the advice of the Government, to terms of imprisonment of up to 40 years. The Twenty-first Amendment to the constitution, passed by referendum in 2001, prohibits the reintroduction of the death penalty, even during a state of emergency or war. Capital punishment is also forbidden by several human rights treaties to which the state is a party.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in South Korea. As of December 2012, there were at least 60 people on death row in South Korea. The method of execution is hanging.

Hanging has been practiced legally in the United States of America from before the nation's birth, up to 1972 when the United States Supreme Court found capital punishment to be in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Four years later, the Supreme Court overturned its previous ruling, and in 1976, capital punishment was again legalized in the United States. As of 2023, only New Hampshire has a law specifying hanging as an available secondary method of execution, and even then only for the one remaining capital punishment sentence in the state.

Capital punishment in Montenegro was first prescribed by law in 1798. It was abolished on 19 June 2002. The last execution, by shooting, took place on 29 January 1981, and the two last death sentences were pronounced on 11 October 2001. Montenegro is bound by the following international conventions prohibiting capital punishment : Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as Protocols No. 6 and No. 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights. Article 26 of the Montenegrin Constitution (2007) that outlawed the death penalty states: "In Montenegro, capital punishment punishment is forbidden”.

Capital punishment in Thailand is a legal penalty, and the country is, as of 2021, one of 54 nations to retain capital punishment both in legislation and in practice. Of the 10 ASEAN nations, only Cambodia and the Philippines have outlawed it, though Laos and Brunei have not conducted executions for decades.

Drowning as a method of execution is attested very early in history, for a large variety of cultures and as the method of execution for many types of offences.

Capital punishment in Islam is traditionally regulated by the Islamic law (sharīʿa), which derived from the Quran, ḥadīth literature, and sunnah. Crimes according to the sharīʿa law which could result in capital punishment include apostasy from Islam, murder, rape, adultery, homosexuality, etc. Death penalty is in use in many Muslim-majority countries, where it is utilised as sharīʿa-prescribed punishment for crimes such as apostasy from Islam, adultery, witchcraft, murder, rape, and publishing pornography.

Iceland observes UTC±00:00 year-round, known as Greenwich Mean Time or Western European Time. UTC±00:00 was adopted on 7 April 1968 – in order for Iceland to be in sync with Europe – replacing UTC−01:00, which had been the standard time zone since 16 November 1907. Iceland previously observed daylight saving time, moving the clock forward one hour, between 1917 and 1921, and 1939 and 1968. The start and end dates varied, as decided by the government. Between 1941 and 1946, daylight saving time commenced on the first Sunday in March and ended in late October, and between 1947 and 1967 it commenced on the first Sunday in April, in all instances since 1941 occurring and ending at 02:00. Since 1994, there have been an increasing number of proposals made to the Althing to reintroduce daylight saving time for a variety of reasons, but all such proposals and resolutions have been rejected.

Agnes Magnúsdóttir was the last person to be executed in Iceland, along with Friðrik Sigurðsson. The pair were sentenced to death for the murder of Nathan Ketilsson, a farmer in Illugastaðir in Vatnsnes, and Pétur Jónsson from Geitaskarð on 14 March 1828. They were executed by beheading in Vatnsdalshólar in Austur-Húnavatnssýsla on 12 January 1830.

Björn Auðunsson Blöndal was an Icelandic District Commissioner and politician. He was a member of Alþingi from 1845 to 1846.

Capital punishment in Burkina Faso has been abolished. In late May 2018, the National Assembly of Burkina Faso adopted a new penal code that omitted the death penalty as a sentencing option, thereby abolishing the death penalty for all crimes.