Capital punishment in the United Kingdom predates the formation of the UK, having been used in Britain and Ireland from ancient times until the second half of the 20th century. The last executions in the United Kingdom were by hanging, and took place in 1964; capital punishment for murder was suspended in 1965 and finally abolished in 1969. Although unused, the death penalty remained a legally defined punishment for certain offences such as treason until it was completely abolished in 1998; the last to be executed for treason was William Joyce, in 1946. In 2004, Protocol No. 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights became binding on the United Kingdom; it prohibits the restoration of the death penalty as long as the UK is a party to the convention.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Belarus. At least one execution was carried out in the country in 2022.

Capital punishment in France is banned by Article 66-1 of the Constitution of the French Republic, voted as a constitutional amendment by the Congress of the French Parliament on 19 February 2007 and simply stating "No one can be sentenced to the death penalty". The death penalty was already declared illegal on 9 October 1981 when President François Mitterrand signed a law prohibiting the judicial system from using it and commuting the sentences of the seven people on death row to life imprisonment. The last execution took place by guillotine, being the main legal method since the French Revolution; Hamida Djandoubi, a Tunisian citizen convicted of torture and murder on French soil, was put to death in September 1977 in Marseille.

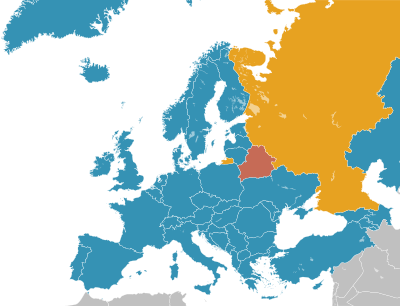

Capital punishment has been completely abolished in all European countries except for Belarus and Russia, the latter of which has a moratorium and has not carried out an execution since September 1996. The complete ban on capital punishment is enshrined in both the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (EU) and two widely adopted protocols of the European Convention on Human Rights of the Council of Europe, and is thus considered a central value. Of all modern European countries, San Marino, Portugal, and the Netherlands were the first to abolish capital punishment, whereas only Belarus still practises capital punishment in some form or another. In 2012, Latvia became the last EU member state to abolish capital punishment in wartime.

Capital punishment is forbidden by the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms of the Czech Republic and is simultaneously prohibited by international legal obligations arising from the Czech Republic's membership of both the Council of Europe and the European Union.

Capital punishment in Germany has been abolished for all crimes, and is now explicitly prohibited by the constitution. It was abolished in West Germany in 1949, in the Saarland in 1956, and East Germany in 1987. The last person executed in Germany was the East German Werner Teske, who was executed at Leipzig Prison in 1981.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Taiwan. The list of capital offences, for which the death penalty can be imposed includes murder, treason, drug trafficking, piracy, terrorism, and especially serious cases of robbery, rape, and kidnapping, as well as military offences, such as desertion during war time. In practice, however, all executions in Taiwan since the early 2000s have been for murder.

Capital punishment is forbidden in Switzerland under article 10, paragraph 1 of the Swiss Federal Constitution. Capital punishment was abolished from federal criminal law in 1942, but remained available in military criminal law until 1992. The last actual executions in Switzerland took place during World War II.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Pakistan. Although there have been numerous amendments to the Constitution, there is yet to be a provision prohibiting the death penalty as a punitive remedy.

Capital punishment in Malaysia is used as a penalty within it's legal system for various crimes. There are currently 27 capital crimes in Malaysia, including murder, drug trafficking, treason, acts of terrorism, waging war against the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, and, since 2003, rape resulting in death, or the rape of a child. Executions are carried out by hanging. Capital punishment was mandatory for 11 crimes for many years. In October 2018, the government imposed a moratorium on all executions with a view to repeal the death penalty altogether, before it changed its stance and agreed to keep the death penalty but would make it discretionary.

Constitutional Court of the Republic of Lithuania is the constitutional court of the Republic of Lithuania, established by the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania of 1992. It began the activities after the adoption of the Law of Constitutional Court of the Republic of Lithuania on 3 February 1993. Since its inception, the court has been located in Vilnius.

Capital punishment remained in Polish law until September 1, 1998, but from 1989 executions were suspended, the last one taking place one year earlier. No death penalty is envisaged in the current Polish penal law.

Capital punishment in Georgia was completely abolished on 1 May 2000 when the country signed Protocol 6 to the ECHR. Later Georgia also adopted the Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR. Capital punishment was replaced with life imprisonment.

Capital punishment in the Republic of Ireland was abolished in statute law in 1990, having been abolished in 1964 for most offences including ordinary murder. The last person to be executed was Michael Manning, hanged for murder in 1954. All subsequent death sentences in the Republic of Ireland, the last handed down in 1985, were commuted by the President, on the advice of the Government, to terms of imprisonment of up to 40 years. The Twenty-first Amendment to the constitution, passed by referendum in 2001, prohibits the reintroduction of the death penalty, even during a state of emergency or war. Capital punishment is also forbidden by several human rights treaties to which the state is a party.

Capital punishment in Romania was abolished in 1990, and has been prohibited by the Constitution of Romania since 1991.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Nigeria.

Capital punishment remains a legal penalty for multiple crimes in The Gambia. However, the country has taken recent steps towards abolishing the death penalty.

Capital punishment in Burkina Faso has been abolished. In late May 2018, the National Assembly of Burkina Faso adopted a new penal code that omitted the death penalty as a sentencing option, thereby abolishing the death penalty for all crimes.

Ethiopia retains capital punishment while not ratified the Second Optional Protocol (ICCR) of UN General Assembly resolution. Historically, capital punishments was codified under Fetha Negest in order to fulfill societal desire. Death penalty can be applied through approval of the President, but executions are rare.

The farmers' strike in Suvalkija was a civil unrest in interwar Lithuania in 1935. It mostly affected Suvalkija where farmers demanded aid to help with a severe economic crisis.