Related Research Articles

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in such a manner is known as a death sentence, and the act of carrying out the sentence is known as an execution. A prisoner who has been sentenced to death and awaits execution is condemned and is commonly referred to as being "on death row". Etymologically, the term capital refers to execution by beheading, but executions are carried out by many methods, including hanging, shooting, lethal injection, stoning, electrocution, and gassing.

Capital punishment, also called the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as a punishment for a crime. It has historically been used in almost every part of the world. Since the mid-19th century many countries have abolished or discontinued the practice. In 2022, the five countries that executed the most people were, in descending order, China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United States.

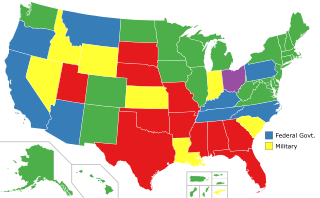

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty in 27 states, throughout the country at the federal level, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in the other 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C. It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 20 of them have authority to execute death sentences, with the other 7, as well as the federal government and military, subject to moratoriums.

Capital punishment is a legal punishment under the criminal justice system of the United States federal government. It is the most serious punishment that could be imposed under federal law. The serious crimes that warrant this punishment include treason, espionage, murder, large-scale drug trafficking, or attempted murder of a witness, juror, or court officer in certain cases.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Japan. The Penal Code of Japan and several laws list 14 capital crimes. In practice, though, it is applied only for aggravated murder. Executions are carried out by long drop hanging, and take place at one of the seven execution chambers located in major cities across the country. The only crime punishable by a mandatory death sentence is instigation of foreign aggression.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Russia but is not used due to a moratorium and no death sentences or executions have been carried out since 2 August 1996. Russia has had an implicit moratorium in place since one was established by President Boris Yeltsin in 1996, and explicitly established by the Constitutional Court of Russia in 1999 and reaffirmed in 2009.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Pakistan. Although there have been numerous amendments to the Constitution, there is yet to be a provision prohibiting the death penalty as a punitive remedy.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in South Korea. As of August 2023, there were 59 people on death row in South Korea. The method of execution is hanging.

Capital punishment in Kazakhstan was abolished for all crimes in 2021. Until 2021, it had been abolished for ordinary crimes but was still permitted for crimes occurring in special circumstances. The legal method of execution in Kazakhstan had been shooting, specifically a single shot to the back of the head.

Capital punishment remains a legal penalty for multiple crimes in The Gambia. However, the country has taken recent steps towards abolishing the death penalty.

Capital punishment in Malawi is a legal punishment for certain crimes. The country abolished the death penalty following a Malawian Supreme Court ruling in 2021, but it was soon reinstated. However, the country is currently under a death penalty moratorium, which has been in place since the latest execution in 1992.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in the Comoros. Currently, however, the country has a de facto moratorium in place; although the death penalty remains in the nation's penal code, it has not been used since the 1990s.

Capital punishment is no longer a legal punishment in Rwanda. The death penalty was abolished in the country in 2007.

Capital punishment in Lesotho is legal. However, despite not having any official death penalty moratorium in place, the country has not carried out any executions since the 1990s and is therefore considered de facto abolitionist.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Cameroon. However, the country not carried out any official executions since 1997, making it de facto abolitionist, since it also has a moratorium.

Capital punishment was abolished for all crimes in Chad on April 28, 2020, following a unanimous vote by the National Assembly of Chad. Prior to April 2020, Chad's 003/PR/2020 "anti-terrorism" law maintained capital punishment for terrorism-related offenses. Chad's new penal code, which was adopted in 2014 and promulgated in 2017, had abolished capital punishment for all other crimes.

Capital punishment in Burkina Faso has been abolished. In late May 2018, the National Assembly of Burkina Faso adopted a new penal code that omitted the death penalty as a sentencing option, thereby abolishing the death penalty for all crimes.

Capital punishment in Myanmar is a legal penalty. Myanmar is classified as a "retentionist" state. Before 25 July 2022, Myanmar was considered "abolitionist in practice," meaning a country has not executed anyone in the past ten years or more and is believed to have an established practice or policy against carrying out executions. Between 1988 and 2022, no legal executions were carried out in the country. In July 2022, four democratic activists, including Zayar Thaw and Kyaw Min Yu, were executed.

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in Uganda. The death penalty was likely last carried out in 1999, although some sources say the last execution in Uganda took place in 2005. Regardless, Uganda is interchangeably considered a retentionist state with regard to capital punishment, due to absence of "an established practice or policy against carrying out executions," as well as a de facto abolitionist state due to the lack of any executions for over one decade.

References

- ↑ "Congo reinstates the death penalty after more than 20 years as it struggles to deal with militants". ABC News. Associated Press. 2024-03-15. Archived from the original on 2024-03-31. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ↑ "The Death Penalty in Democratic Republic of the Congo". www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ↑ "Simon Kimbangu". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- ↑ David van Reybrouck (25 March 2014). Congo: The Epic History of a People . HarperCollins, 2014. p. 142ff. ISBN 978-0-06-220011-2.

- ↑ "Central and Eastern Africa: IRIN Update 342 for 28 Jan 98.1.28". University of Pennsylvania – African Studies Center. 28 January 1998. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- 1 2 Amnesty (18 May 1999). "Scores of executions in the Democratic Republic of Congo". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ Amnesty (31 May 2000). "Democratic Republic of Congo: Killing Human Decency" (PDF). RefWorld. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ "Congo, Democratic Republic of the | Country Reports on Human Rights Practices". United States Department of State Archives. 4 March 2002. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- 1 2 "Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Death Penalty". Parliamentarians for Global Action. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dudley, Bronwyn (12 March 2020). "Death Sentences in the Democratic Republic of the Congo More Numerous than Previously Thought". World Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- 1 2 "DR Congo death penalty verdict prompts concern". BBC News. 6 May 2010. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 "DR Congo court sentences 51 to death over killing of UN experts". Al Jazeera. 29 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ "Ten years of deliberate impunity in radio journalist's murder". Reporters Without Borders. 13 June 2017. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ "Thirty sentenced to death over anti-police clashes in DR Congo". Al Jazeera. 15 May 2021. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ "DR Congo Eid clashes: Court hands down death sentences – BBC News". BBC News. 15 May 2021. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- 1 2 "DR Congo court sentences 51 in trial over 2017 murder of UN experts". France 24. 29 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ Mehta, Pooja (2 February 2022). "UN calls for continued moratorium on death penalty in DRC". Jurist. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ "Following DR Congo murder trial, UN calls for death penalty moratorium to remain". United Nations News. 1 February 2022. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ Zenda, Cyril. "Death sentences surge as DRC lifts execution ban". FairPlanet. Retrieved 2025-01-06.

- ↑ "Congo reinstates the death penalty after more than 20 years as it struggles to deal with militants". AP News. 2024-03-15. Retrieved 2025-01-06.

- ↑ "DR Congo reinstates death penalty after 21 years amid escalating violence and militant attacks". www.jurist.org. 2024-03-17. Retrieved 2025-01-06.

- ↑ Fournier, Emilie (2024-03-18). "Lifting of the Moratorium in the DRC: ECPM and CPJ call for the non-instrumentalisation of the death penalty". ECPM. Retrieved 2025-01-06.

- ↑ Zenda, Cyril. "DR Congo's death penalty revival: A dangerous shift". FairPlanet. Retrieved 2025-01-06.

- ↑ "A military court sentences 8 Congolese army soldiers to death for cowardice, other crimes". AP News. 2024-05-03. Retrieved 2025-01-07.

- ↑ "Congo will execute more than 170 people convicted of armed robbery, official says". AP News. 2025-01-05. Retrieved 2025-01-07.

- ↑ "Congo executes 102 'urban bandits' with 70 more set to be killed, officials say". ABC News. Retrieved 2025-01-07.

- 1 2 "DRC: Detention conditions of people sentenced to death". Prison Insider. 18 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.