Eswatini, officially the Kingdom of Eswatini and also known as Swaziland, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Mozambique to its northeast and South Africa to its north, west and south. At no more than 200 kilometres (120 mi) north to south and 130 kilometres (81 mi) east to west, Eswatini is one of the smallest countries in Africa; despite this, its climate and topography are diverse, ranging from a cool and mountainous highveld to a hot and dry lowveld.

Mswati III is the King of Eswatini and head of the Swazi Royal Family. He was born in Manzini, Eswatini, to King Sobhuza II and one of his younger wives, Ntfombi Tfwala. He was Tfwala’s only child. He attended primary school at Masundvwini Primary School and secondary school at Lozitha Palace School. From 1983 to 1986, he attended Sherborne School in north-west Dorset, England. He was crowned as Mswati III, Ingwenyama and King of Swaziland, on 25 April 1986 at the age of 18, thus becoming the youngest ruling monarch in the world at that time. Together with his mother, Ntfombi Tfwala, now Queen Mother (Ndlovukati), he rules the country as an absolute monarch. Mswati III is known for his practice of polygamy and currently has 15 wives. Although he is respected and fairly popular in Eswatini, his policies and lavish lifestyle have led to local protests and international criticism.

Trafficking of children is a form of human trafficking and is defined as the "recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, and/or receipt" of a child for the purpose of slavery, forced labor and exploitation. This definition is substantially wider than the same document's definition of "trafficking in persons". Children may also be trafficked for the purpose of adoption.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Eswatini are limited. LGBT people face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. According to Rock of Hope, a Swazi LGBT advocacy group, "there is no legislation recognising LGBTIs or protecting the right to a non-heterosexual orientation and gender identity and as a result LGBTI cannot be open about their orientation or gender identity for fear of rejection and discrimination". Homosexuality is illegal in Eswatini, though this law is in practice not enforced.

The global march against child labor came about in 1998, following the significant response concerning the desire to end child labor. It was a grassroot movement that motivated many individuals and organizations to come together and fight against child labor and not an annual march.

Bulembu is a small town located in northwestern Hhohho, Eswatini, 10 km west of the town of Piggs Peak. Located above the Komati Valley in Swaziland’s Highveld, Bulembu is named after the siSwati word for a spider's web.

Eswatini–United States relations are bilateral relations between Eswatini and the United States.

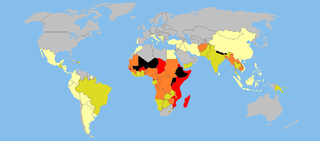

HIV/AIDS in Eswatini was first reported in 1986 but has since reached epidemic proportions due in large part to cultural beliefs which discourage safe-sex practices. Coupled with a high rate of co-infection with tuberculosis, life expectancy has halved in the first decade of the millennium. Eswatini has the highest prevalence of HIV as percentage of population in the world as of 2016 (27.2%). The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Eswatini, having contributed largely to high mortality rates among productive Swazi age groups, has adversely affected the country’s socioeconomic status and hindered its development.

Child labour in Bangladesh is common, with 4.7 million or 12.6% of children aged 5 to 14 in the work force. Out of the child labourers engaged in the work force, 83% are employed in rural areas and 17% are employed in urban areas. Child labour can be found in agriculture, poultry breeding, fish processing, the garment sector and the leather industry, as well as in shoe production. Children are involved in jute processing, the production of candles, soap and furniture. They work in the salt industry, the production of asbestos, bitumen, tiles and ship breaking.

Prostitution in Eswatini is illegal, the anti-prostitution laws dating back to 1889, when the country Eswatini was a protectorate of South Africa. Law enforcement is inconsistent, particularly near industrial sites and military bases. Police tend to turn a blind eye to prostitution in clubs. There are periodic clamp-downs by the police.

Child Labour is the practice of having children engage in economic activity, on a part- or full-time basis. The practice deprives children of their childhood, and is harmful to their physical and mental development. Poverty, lack of good schools and the growth of the informal economy are considered to be the key causes of child labour in India. Some other causes of Child Labor in India are cheap wages and accessibility to factories that can produce the maximum amount of goods for the lowest possible price. Corruption in the government of India also plays a major role in child labour because laws that should be enforced to prevent child labor are not because of the corrupt government.

Eswatini, Africa's last remaining absolute monarchy, was rated by Freedom House from 1972 to 1992 as "Partly Free"; since 1993, it has been considered "Not Free". During these years the country's Freedom House rating for "Political Rights" has slipped from 4 to 7, and "Civil Liberties" from 2 to 5. Political parties have been banned in Eswatini since 1973. A 2011 Human Rights Watch report described the country as being "in the midst of a serious crisis of governance", noting that "[y]ears of extravagant expenditure by the royal family, fiscal indiscipline, and government corruption have left the country on the brink of economic disaster". In 2012, the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR) issued a sharp criticism of Eswatini's human-rights record, calling on the Swazi government to honor its commitments under international law in regards to freedom of expression, association, and assembly. HRW notes that owing to a 40% unemployment rate and low wages that oblige 80% of Swazis to live on less than US$2 a day, the government has been under "increasing pressure from civil society activists and trade unionists to implement economic reforms and open up the space for civil and political activism" and that dozens of arrests have taken place "during protests against the government's poor governance and human rights record".

Eswatini is a source, destination, and transit country for women and children subjected to trafficking in persons, specifically commercial sexual exploitation, involuntary domestic servitude, and forced labor in agriculture. Swazi girls, particularly orphans, are subjected to commercial sexual exploitation and involuntary domestic servitude in the cities of Mbabane and Manzini, as well as in South Africa and Mozambique.

Child labour in Pakistan is the employment of children for work in Pakistan, which causes them mental, physical, moral and social harm. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan estimated that in the 1990s, 11 million children were working in the country, half of whom were under age ten. In 1996, the median age for a child entering the work force was seven, down from eight in 1994. It was estimated that one quarter of the country's work force was made up of children.

Child labour refers to the full-time employment of children under a minimum legal age. In 2003, an International Labour Organization (ILO) survey reported that one in every ten children in the capital above the age of seven was engaged in child domestic labour. Children who are too young to work in the fields work as scavengers. They spend their days rummaging in dumps looking for items that can be sold for money. Children also often work in the garment and textile industry, in prostitution, and in the military.

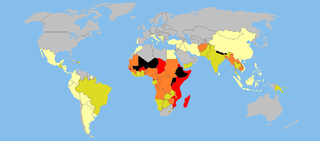

Child labour in Africa is generally defined based on two factors: type of work and minimum appropriate age of the work. If a child is involved in an activity that is harmful to his/her physical and mental development, he/she is generally considered as a child labourer. That is, Any work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children, and interferes with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work. Appropriate minimum age for each work depends on the effects of the work on the physical health and mental development of children. ILO Convention No. 138 suggests the following minimum age for admission to employment under which, if a child works, he/she is considered as a child laborer: 18 years old for hazardous works, and 13-15 years old for light works, although 12-14 years old may be permitted for light works under strict conditions in very poor countries. Another definition proposed by ILO’s Statistical Information and Monitoring Program on Child Labor (SIMPOC) defines a child as a child labourer if he/she is involved in an economic activity, and is under 12 years old and works one or more hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least 14 hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least one hour per week in activities that are hazardous, or is 17 or under and works in an “unconditional worst form of child labor”.

Child Labor in the Philippines is the employment of children in hazardous occupations below the age of eighteen (18), or without the proper conditions and requirements below the age of fifteen (15), where children are compelled to work on a regular basis to earn a living for themselves and their families, and as a result are disadvantaged educationally and socially.

Child labor in Bolivia is a widespread phenomenon. A 2014 document on the worst forms of child labor released by the U.S. Department of Labor estimated that approximately 20.2% of children between the ages of 7 and 14, or 388,541 children make up the labor force in Bolivia. Indigenous children are more likely to be engaged in labor than children who reside in urban areas. The activities of child laborers are diverse, however the majority of child laborers are involved in agricultural labor, and this activity varies between urban and rural areas. Bolivia has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990. Bolivia has also ratified the International Labour Organization’s Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (138) and the ILO’s worst forms of child labor convention (182). In July 2014, the Bolivian government passed the new child and adolescent code, which lowered the minimum working age to ten years old given certain working conditions The new code stipulates that children between the ages of ten and twelve can legally work given they are self-employed while children between 12 and 14 may work as contracted laborers as long as their work does not interfere with their education and they work under parental supervision.

The Republic of Armenia was admitted into the United Nations on March 2, 1992. Since December 1992 when UN opened its first office in Yerevan, Armenia signed and ratified many international treaties. There are fifteen specialized agencies, programs and funds in the UN Country Team under the supervision of the UN Resident Coordinator. Besides, the World Bank (WB), International Finance Corporation (IFC) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) have offices in the country. The focus is drawn to the attainment of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) stipulated by the Millennium Declaration adopted during the Millennium Summit in 2000. The MDGs have simulated never before practiced actions to meet the needs of the world's poorest. As the MDG achievement date of December 2015 draws closer a new set of global sustainable development goals is consulted worldwide, to be adopted by the UN General Assembly in September 2015. Armenia was included in the initial group of 50 countries to conduct national consultations on the global Post-2015 development agenda.