Related Research Articles

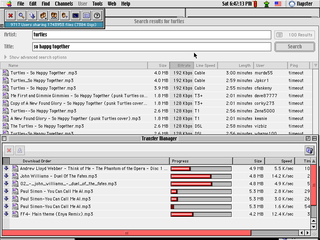

Napster was an American peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing application primarily associated with digital audio file distribution. Founded by Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker, the platform originally launched on June 1, 1999. Audio shared on the service was typically encoded in the MP3 format. As the software became popular, the company encountered legal difficulties over copyright infringement. Napster ceased operations in 2001 after losing multiple lawsuits and filed for bankruptcy in June 2002.

Free music or libre music is music that, like free software, can freely be copied, distributed and modified for any purpose. Thus free music is either in the public domain or licensed under a free license by the artist or copyright holder themselves, often as a method of promotion. It does not mean that there should be no fee involved. The word free refers to freedom, not to price.

Criticism of copyright, or anti-copyright sentiment, is a dissenting view of the current state of copyright law or copyright as a concept. Critics often discuss philosophical, economical, or social rationales of such laws and the laws' implementations, the benefits of which they claim do not justify the policy's costs to society. They advocate for changing the current system, though different groups have different ideas of what that change should be. Some call for remission of the policies to a previous state—copyright once covered few categories of things and had shorter term limits—or they may seek to expand concepts like fair use that allow permissionless copying. Others seek the abolition of copyright itself.

A private copying levy is a government-mandated scheme in which a special tax or levy is charged on purchases of recordable media. Such taxes are in place in various countries and the income is typically allocated to the developers of "content".

As used by copyright theorists, the term copynorm is used to refer to a normalized social standard regarding the ethical issue of duplicating copyrighted material.

An anonymous P2P communication system is a peer-to-peer distributed application in which the nodes, which are used to share resources, or participants are anonymous or pseudonymous. Anonymity of participants is usually achieved by special routing overlay networks that hide the physical location of each node from other participants.

A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc., 239 F.3d 1004 was a landmark intellectual property case in which the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed a district court ruling that the defendant, peer-to-peer file sharing service Napster, could be held liable for contributory infringement and vicarious infringement of copyright. This was the first major case to address the application of copyright laws to peer-to-peer file sharing.

Peer-to-peer file sharing is the distribution and sharing of digital media using peer-to-peer (P2P) networking technology. P2P file sharing allows users to access media files such as books, music, movies, and games using a P2P software program that searches for other connected computers on a P2P network to locate the desired content. The nodes (peers) of such networks are end-user computers and distribution servers.

Loi DADVSI is the abbreviation of the French Loi relative au droit d’auteur et aux droits voisins dans la société de l’information. It is a bill reforming French copyright law, mostly in order to implement the 2001 Information Society Directive, which in turn implements a 1996 WIPO treaty.

File sharing in Canada relates to the distribution of digital media in that country. Canada had the greatest number of file sharers by percentage of population in the world according to a 2004 report by the OECD. In 2009 however it was found that Canada had only the tenth greatest number of copyright infringements in the world according to a report by BayTSP, a U.S. anti-piracy company.

Steal This Film is a film series documenting the movement against intellectual property directed by Jamie King, produced by The League of Noble Peers and released via the BitTorrent peer-to-peer protocol.

File sharing is the practice of distributing or providing access to digital media, such as computer programs, multimedia, program files, documents or electronic books/magazines. It involves various legal aspects as it is often used to exchange data that is copyrighted or licensed.

Good Copy Bad Copy is a 2007 documentary film about copyright and culture in the context of Internet, peer-to-peer file sharing and other technological advances, directed by Andreas Johnsen, Ralf Christensen, and Henrik Moltke. It features interviews with many people with various perspectives on copyright, including copyright lawyers, producers, artists and filesharing service providers.

Copyright infringement is the use of works protected by copyright without permission for a usage where such permission is required, thereby infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the copyright holder, such as the right to reproduce, distribute, display or perform the protected work, or to produce derivative works. The copyright holder is usually the work's creator, or a publisher or other business to whom copyright has been assigned. Copyright holders routinely invoke legal and technological measures to prevent and penalize copyright infringement.

File sharing is the practice of distributing or providing access to digital media, such as computer programs, multimedia, documents or electronic books. Common methods of storage, transmission and dispersion include removable media, centralized servers on computer networks, Internet-based hyperlinked documents, and the use of distributed peer-to-peer networking.

Music piracy is the copying and distributing of recordings of a piece of music for which the rights owners did not give consent. In the contemporary legal environment, it is a form of copyright infringement, which may be either a civil wrong or a crime depending on jurisdiction. The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw much controversy over the ethics of redistributing media content, how much production and distribution companies in the media were losing, and the very scope of what ought to be considered piracy – and cases involving the piracy of music were among the most frequently discussed in the debate.

Metallica, et al. v. Napster, Inc. was a 2000 U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California case that focused on copyright infringement, racketeering, and unlawful use of digital audio interface devices. Metallica vs. Napster, Inc. was the first case that involved an artist suing a peer-to-peer file sharing ("P2P") software company.

The ancillary copyright for press publishers is a proposal incorporated in 2012 legislation proposed by the ruling coalition of the German government, led by Angela Merkel of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), to extend publishers' copyrights. The bill was agreed by the Cabinet at the end of August 2012 and submitted to parliament on 14 November 2012. It was passed by the Bundestag on 1 March 2013 by 293 to 243, following substantial changes in the week before the vote.

Javier de la Cueva, is a lawyer specialized in issues related to technology and the Internet. He graduated in Law and is Doctor in Philosophy from the Complutense University of Madrid. He has defended numerous cases involving the use of free licenses of intellectual property.

Open source is source code that is made freely available for possible modification and redistribution. Products include permission to use and view the source code, design documents, or content of the product. The open source model is a decentralized software development model that encourages open collaboration. A main principle of open source software development is peer production, with products such as source code, blueprints, and documentation freely available to the public. The open source movement in software began as a response to the limitations of proprietary code. The model is used for projects such as in open source appropriate technology, and open source drug discovery.

References

- ↑ Gervais, D. "The Price of Social Norms: Towards a Liability Regime for File Sharing", 12 Journal of Intellectual Property Law 39, 2004.

- ↑ Baker, D. The Artistic Freedom Voucher: Internet Age Alternative to Copyrights Archived 2019-12-15 at the Wayback Machine 2003. "Related Views"

- ↑ Mark Stanley Archived 2014-05-17 at the Wayback Machine , The False Freedom of Art Vouchers

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-06-17. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "The World is Going Flat(-Rate)". 11 May 2009.