Herbert Marshall McLuhan was a Canadian philosopher whose work is among the cornerstones of the study of media theory. He studied at the University of Manitoba and the University of Cambridge. He began his teaching career as a professor of English at several universities in the United States and Canada before moving to the University of Toronto in 1946, where he remained for the rest of his life. He is known as the "father of media studies".

Media studies is a discipline and field of study that deals with the content, history, and effects of various media; in particular, the mass media. Media studies may draw on traditions from both the social sciences and the humanities, but it mostly draws from its core disciplines of mass communication, communication, communication sciences, and communication studies.

Harold Adams Innis was a Canadian professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on media, communication theory, and Canadian economic history. He helped develop the staples thesis, which holds that Canada's culture, political history, and economy have been decisively influenced by the exploitation and export of a series of "staples" such as fur, fish, lumber, wheat, mined metals, and coal. The staple thesis dominated economic history in Canada from the 1930s to 1960s, and continues to be a fundamental part of the Canadian political economic tradition. Innis has been referred to as the "father of communications theory" and as the "father of Canadian economic history".

Media ecology theory is the study of media, technology, and communication and how they affect human environments. The theoretical concepts were proposed by Marshall McLuhan in 1964, while the term media ecology was first formally introduced by Neil Postman in 1968.

Lewis Mumford was an American historian, sociologist, philosopher of technology, and literary critic. Particularly noted for his study of cities and urban architecture, he had a broad career as a writer. He made significant contributions to social philosophy, American literary and cultural history, and the history of technology.

The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man is a 1962 book by Marshall McLuhan, in which he analyzes the effects of mass media, especially the printing press, on European culture and human consciousness. It popularized the term global village, which refers to the idea that mass communication allows a village-like mindset to apply to the entire world; and Gutenberg Galaxy, which we may regard today to refer to the accumulated body of recorded works of human art and knowledge, especially books.

Ursula Martius Franklin was a Canadian metallurgist, activist, research physicist, author, and educator who taught at the University of Toronto for more than 40 years. Franklin is best known for her writings on the political and social effects of technology. She was the author of The Real World of Technology, which is based on her 1989 Massey Lectures; The Ursula Franklin Reader: Pacifism as a Map, a collection of her papers, interviews, and talks; and Ursula Franklin Speaks: Thoughts and Afterthoughts, containing 22 of her speeches and five interviews between 1986 and 2012. Franklin was a practising Quaker and actively worked on behalf of pacifist and feminist causes. She wrote and spoke extensively about the futility of war and the connection between peace and social justice. Franklin received numerous honours and awards, including the Governor General's Award in Commemoration of the Persons Case for promoting the equality of girls and women in Canada and the Pearson Medal of Peace for her work in advancing human rights. In 2012, she was inducted into the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame. A Toronto high school, Ursula Franklin Academy, as well as Ursula Franklin Street on the University of Toronto campus, have been named in her honor.

Empire and Communications is a book published in 1950 by University of Toronto professor Harold Innis. It is based on six lectures Innis delivered at Oxford University in 1948. The series, known as the Beit Lectures, was dedicated to exploring British imperial history. Innis, however, decided to undertake a sweeping historical survey of how communications media influence the rise and fall of empires. He traced the effects of media such as stone, clay, papyrus, parchment and paper from ancient to modern times.

Medium theory is a mode of analysis that examines the ways in which particular communication media and modalities impact the specific content (messages) they are meant to convey. It Medium theory refers to a set of approaches that can be used to convey the difference in meanings of messages depending on the channel through which they are transmitted. Medium theorists argue that media are not simply channels for transmitting information between environments, but are themselves distinct social-psychological settings or environments that encourage certain types of interaction and discourage others.

Orality is thought and verbal expression in societies where the technologies of literacy are unfamiliar to most of the population. The study of orality is closely allied to the study of oral tradition.

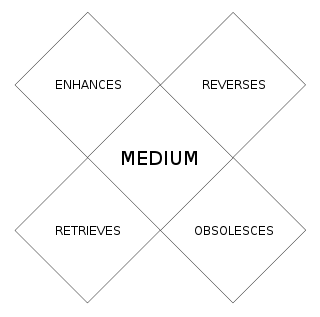

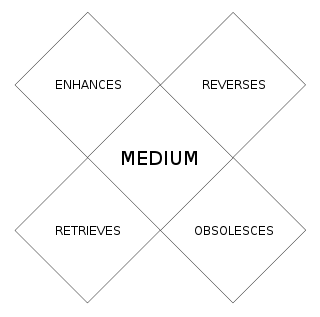

Marshall McLuhan's tetrad of media effects uses a tetrad - a four-part construct - to examine the effects on society of any technology/medium by dividing its effects into four categories and displaying them simultaneously. The tetrad first appeared in print in articles by McLuhan in the journals Technology and Culture (1975) and et cetera (1977). It first appeared in book form in his posthumously-published works Laws of Media (1988) and The Global Village (1989).

The alphabet effect is a group of hypotheses in communication theory arguing that phonetic writing, and alphabetic scripts in particular, have served to promote and encourage the cognitive skills of abstraction, analysis, coding, decoding, and classification. Promoters of these hypotheses are associated with the Toronto School of Communication, such as Marshall McLuhan, Harold Innis, Walter Ong, Vilém Flusser and more recently Robert K. Logan; the term "alphabet effect" comes from Logan's 1986 work.

The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History is a book written by Harold Innis covering the fur trade era in Canada from the early 16th century to the 1920s. First published in 1930, it comprehensively documents the history of fur trading while extending Innis's analysis of the economic and social implications of Canada's reliance on staple products. The book focuses on the far-reaching effects of new techniques and technologies in the contact between European and Indigenous civilizations and shows how co-operation and rivalries among French, English and Indigenous peoples shaped the history of the northern half of North America. Finally, the book tries to show how Canada emerged as a nation with boundaries largely determined by the fur trade. Canada, Innis argues, "emerged not in spite of geography, but because of it."

The Cod Fisheries: The History of an International Economy is a 1940 book by Harold Innis.

Harold Adams Innis was a professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on Canadian economic history and on media and communication theory. He helped develop the staples thesis, which holds that Canada's culture, political history and economy have been decisively influenced by the exploitation and export of a series of staples such as fur, fish, wood, wheat, mined metals and fossil fuels. Innis's communications writings explore the role of media in shaping the culture and development of civilizations. He argued, for example, that a balance between oral and written forms of communication contributed to the flourishing of Greek civilization in the 5th century BC. But he warned that Western civilization is now imperiled by powerful, advertising-driven media obsessed by "present-mindedness" and the "continuous, systematic, ruthless destruction of elements of permanence essential to cultural activity."

The Toronto School is a school of thought in communication theory and literary criticism, the principles of which were developed chiefly by scholars at the University of Toronto. It is characterized by exploration of Ancient Greek literature and the theoretical view that communication systems create psychological and social states. The school originated from the works of Eric A. Havelock and Harold Innis in the 1930s, and grew to prominence with the contributions of Edmund Snow Carpenter, Northrop Frye, Ursula Franklin, and Marshall McLuhan.

The ritual view of communication is a communications theory proposed by James W. Carey, wherein communication–the construction of a symbolic reality–represents, maintains, adapts, and shares the beliefs of a society in time. In short, the ritual view conceives communication as a process that enables and enacts societal transformation.

Mediated communication or mediated interaction refers to communication carried out by the use of information communication technology and can be contrasted to face-to-face communication. While nowadays the technology we use is often related to computers, giving rise to the popular term computer-mediated communication, mediated technology need not be computerized as writing a letter using a pen and a piece of paper is also using mediated communication. Thus, Davis defines mediated communication as the use of any technical medium for transmission across time and space.

Technological determinism is a reductionist theory in assuming that a society's technology progresses by following its own internal logic of efficiency, while determining the development of the social structure and cultural values. The term is believed to have originated from Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929), an American sociologist and economist. The most radical technological determinist in the United States in the 20th century was most likely Clarence Ayres who was a follower of Thorstein Veblen as well as John Dewey. William Ogburn was also known for his radical technological determinism and his theory on cultural lag.

In the social sciences, materiality is the notion that the physical properties of a cultural artifact have consequences for how the object is used. Some scholars expand this definition to encompass a broader range of actions, such as the process of making art, and the power of organizations and institutions to orient activity around themselves. The concept of materiality is used across many disciplines within the social sciences to focus attention on the impact of material or physical factors. Scholars working in science and technology studies, anthropology, organization studies, or communication studies may incorporate materiality as a dimension of their investigations. Central figures in the social scientific study of materiality are Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan.