Homo heidelbergensis is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human which existed during the Middle Pleistocene. It was subsumed as a subspecies of H. erectus in 1950 as H. e. heidelbergensis, but towards the end of the century, it was more widely classified as its own species. It is debated whether or not to constrain H. heidelbergensis to only Europe or to also include African and Asian specimens, and this is further confounded by the type specimen being a jawbone, because jawbones feature few diagnostic traits and are generally missing among Middle Pleistocene specimens. Thus, it is debated if some of these specimens could be split off into their own species or a subspecies of H. erectus. Because the classification is so disputed, the Middle Pleistocene is often called the "muddle in the middle".

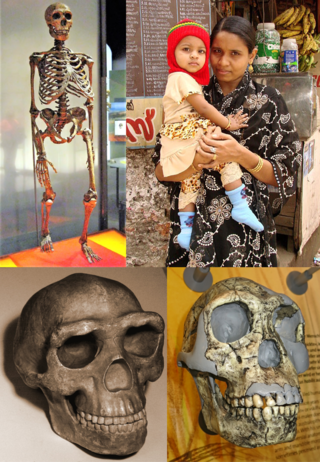

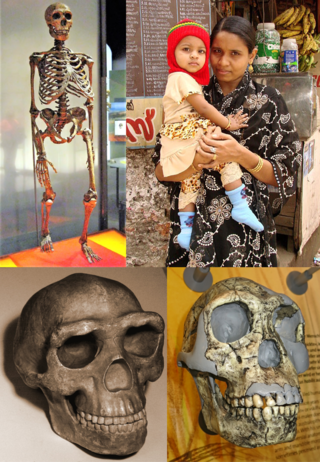

Homo is a genus of great ape that emerged from the genus Australopithecus and encompasses the extant species Homo sapiens and a number of extinct species classified as either ancestral or closely related to modern humans. These include Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis. The oldest member of the genus is Homo habilis, with records of just over 2 million years ago. Homo, together with the genus Paranthropus, is probably most closely related to the species Australopithecus africanus within Australopithecus. The closest living relatives of Homo are of the genus Pan, with the ancestors of Pan and Homo estimated to have diverged around 5.7-11 million years ago during the Late Miocene.

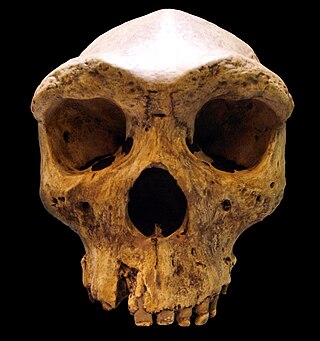

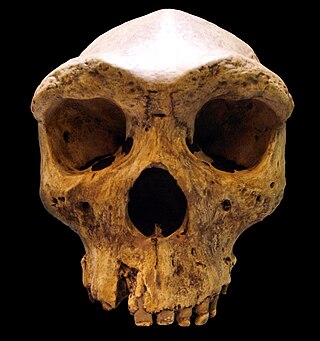

Homo rhodesiensis is the species name proposed by Arthur Smith Woodward (1921) to classify Kabwe 1, a Middle Stone Age fossil recovered from Broken Hill mine in Kabwe, Northern Rhodesia. In 2020, the skull was dated to 324,000 to 274,000 years ago. Other similar older specimens also exist.

Ceprano Man, Argil, and Ceprano Calvarium, is a Middle Pleistocene archaic human fossil, a single skull cap (calvarium), accidentally unearthed in a highway construction project in 1994 near Ceprano in the Province of Frosinone, Italy. It was initially considered Homo cepranensis, Homo erectus, or possibly Homo antecessor; but in recent studies, most regard it either as a form of Homo heidelbergensis sharing affinities with African forms, or an early morph of Neanderthal.

The Steinheim skull is a fossilized skull of a Homo neanderthalensis or Homo heidelbergensis found on 24 July 1933 near Steinheim an der Murr, Germany.

Maba Man is a pre-modern hominin whose remains were discovered in 1958 in caves near the town called Maba, near Shaoguan city in the northern part of Guangdong province, China.

Human taxonomy is the classification of the human species within zoological taxonomy. The systematic genus, Homo, is designed to include both anatomically modern humans and extinct varieties of archaic humans. Current humans have been designated as subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens, differentiated, according to some, from the direct ancestor, Homo sapiens idaltu.

Archaic humans is a broad category denoting all species of the genus Homo that are not Homo sapiens. Among the earliest modern human remains are those from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, Florisbad in South Africa (259 ka), and Omo-Kibish I in southern Ethiopia. Some examples of archaic humans include H. antecessor (1200–770 ka), H. bodoensis (1200–300 ka), H. heidelbergensis (600–200 ka), Neanderthals, H. rhodesiensis (300–125 ka) and Denisovans.

Homo erectus is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Its specimens are among the first recognizable members of the genus Homo.

The Florisbad Skull is an important human fossil of the early Middle Stone Age, representing either late Homo heidelbergensis or early Homo sapiens. It was discovered in 1932 by T. F. Dreyer at the Florisbad site, Free State Province, South Africa.

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins(di-NEE-sə-və) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic, and lived, based on current evidence, from 285 to 25 thousand years ago. Denisovans are known from few physical remains; consequently, most of what is known about them comes from DNA evidence. No formal species name has been established pending more complete fossil material.

The Red Deer Cave people were a prehistoric population of modern humans known from bones dated to between about 17,830 to c. 11,500 years ago, found in Red Deer Cave and Longlin Cave in Yunnan and Guangxi Provinces, in Southwest China.

The Ndutu skull is the partial cranium of a hominin that has been assigned variously to late Homo erectus, Homo rhodesiensis, and early Homo sapiens, from the Middle Pleistocene, found at Lake Ndutu in northern Tanzania.

Penghu 1 is a fossil jaw (mandible) belonging to an extinct hominin species of the genus Homo from Taiwan which lived in the middle-late Pleistocene. The precise classification of the mandible is disputed, some arguing that it represents a new species, Homo tsaichangensis, whereas others believe it to be the fossil of a H. erectus, an archaic H. sapiens or possibly a Denisovan.

Xujiayao, located in the Nihewan Basin in China, is an early Late Pleistocene paleoanthropological site famous for its archaic hominin fossils.

Jinniushan is a Middle Pleistocene paleoanthropological site, dating to around 260,000 BP, most famous for its archaic hominin fossils. The site is located near Yingkou, Liaoning, China. Several new species of extinct birds were also discovered at the site.

Homo longi is an extinct species of archaic human identified from a nearly complete skull, nicknamed 'Dragon Man', from Harbin on the Northeast China Plain, dating to at minimum 146,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene. The skull was discovered in 1933 along the Songhua River while the Dongjiang Bridge was under construction for the Manchukuo National Railway. Due to a tumultuous wartime atmosphere, it was hidden and only brought to paleoanthropologists in 2018. H. longi has been hypothesized to be the same species as the Denisovans, but this cannot be confirmed without genetic testing.

The Salé cranium is a pathological specimen of enigmatic Middle Pleistocene hominin discovered in Salé, Morocco by quarrymen in 1971. Since its discovery, the specimen has variously been classified as Homo sapiens, Homo erectus, Homo rhodesiensis/bodoensis, or Homo heidelbergensis. Its pathological condition and mosaic anatomy has proved difficult to classify. It was discovered with few faunal fossils and no lithics, tentatively dated to 400 ka by some sources.

The Hualongdong people are extinct humans that lived in eastern China around 300,000 years ago during the late Middle Pleistocene. Discovered by a research team led by Xiujie Wu and Liu Wu, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, from the Hualong Cave in Dongzhi County at Anhui Province in 2006, they are known from about 30 fossils that belong to 16 individuals. The first analysis of the skull fragments collected in 2006 suggested that they could be members of Homo erectus. For some of the specimens, their exact position as a human species is not known. More complete fossils found in 2015 indicate that they cannot be directly assigned to any Homo species as they also exhibit archaic human features. They are the first humans in Asia to have both archaic and modern human features. They are likely a distinct species that form a separate branch in the human family tree.

The Narmada Human, originally the Narmada Man, is a species of extinct human that lived in central India during the Middle and Late Pleistocene. From a skull cup discovered from the bank of the Narmada River in Madhya Pradesh in 1982, the discoverer, Arun Sonakia classified it was an archaic human and gave the name Narmada Man, with the scientific name H. erectus narmadensis. Analysis of additional fossils from the same location in 1997 indicated that the individual could be a female, hence, a revised name, Narmada Human, was introduced. It remains the oldest human species in India.