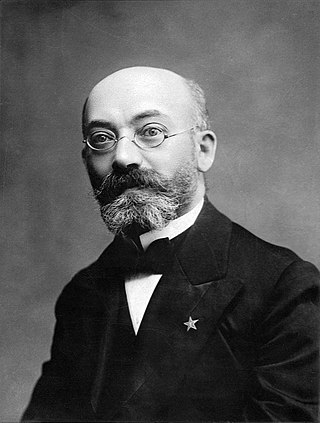

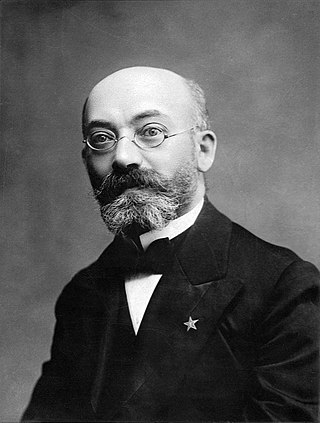

Esperanto is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it is intended to be a universal second language for international communication, or "the international language". Zamenhof first described the language in Dr. Esperanto's International Language, which he published under the pseudonym Doktoro Esperanto. Early adopters of the language liked the name Esperanto and soon used it to describe his language. The word esperanto translates into English as "one who hopes".

Esperantujo or Esperantio is the community of speakers of the Esperanto language and their culture, as well as the places and institutions where the language is used. The term is used "as if it were a country."

L. L. Zamenhof developed Esperanto in the 1870s and '80s. Unua Libro, the first print discussion of the language, appeared in 1887. The number of Esperanto speakers have increased gradually since then, without much support from governments and international organizations. Its use has, in some instances, been outlawed or otherwise suppressed.

L. L. Zamenhof was the creator of Esperanto, the most widely used constructed international auxiliary language.

Dr. Esperanto's International Language, commonly referred to as Unua Libro, is an 1887 book by Polish ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof, in which he first introduced and described the constructed language Esperanto. First published in Russian on July 26 [O.S. July 14] 1887, the publication of Unua Libro marks the formal beginning of the Esperanto movement.

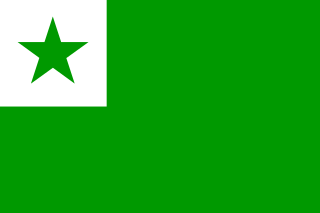

Esperanto symbols, primarily the Esperanto flag, have seen much consistency over the time of Esperanto's existence, though a few variations in exact flag patterning and symbology exist.

An international auxiliary language is a language meant for communication between people from all different nations, who do not share a common first language. An auxiliary language is primarily a foreign language and often a constructed language. The concept is related to but separate from the idea of a lingua franca that people must use to communicate. The study of international auxiliary languages is interlinguistics.

The Akademio de Esperanto is an independent body of Esperanto speakers who steward the evolution of said language by keeping it consistent with the Fundamento de Esperanto in accordance with the Declaration of Boulogne. Modeled somewhat after the Académie française and the Real Academia Española, the Akademio was proposed by L. L. Zamenhof, the creator of Esperanto, at the first World Esperanto Congress, and was founded soon thereafter under the name Lingva Komitato. This Committee had a "superior commission" called the Akademio. In 1948, within the framework of a general reorganization, the Language Committee and the Academy combined to form the Akademio de Esperanto.

Esperanto is a constructed international auxiliary language designed to have a simple phonology. The creator of Esperanto, L. L. Zamenhof, described Esperanto pronunciation by comparing the sounds of Esperanto with the sounds of several major European languages.

In 1894, L. L. Zamenhof, who was the original creator of the constructed language Esperanto, proposed a complete series of reforms to Esperanto. It is notable as the only complete Esperantido to be authored by Zamenhof himself, and it was presented in response to various reforms that had been proposed by others since the language's publication in 1887. The project was eventually rejected by the language's speakers, and subsequently even by Zamenhof himself. Some of the proposed reforms were used in another constructed language, Ido, beginning in 1907.

Esperanto and Interlingua are two planned languages with different approaches to the problem of providing an International auxiliary language (IAL). Esperanto has many more speakers; the number of speakers is c. 100,000-2,000,000. On the other hand, the number of speakers is c. 1,500 for Interlingua, but speakers of the language claim to be able to communicate easily with the c. 1 billion speakers of Romance languages, whereas Esperanto speakers can only communicate among each other.

Esperanto and Ido are constructed international auxiliary languages, with Ido being an Esperantido derived from Esperanto and Reformed Esperanto. The number of speakers is estimated at 100 thousand to 2 million for Esperanto, whereas Ido is much fewer at 100 to 1 thousand.

Fundamento de Esperanto is a 1905 book by L. L. Zamenhof, in which the author explains the basic grammar rules and vocabulary that constitute the basis of the constructed language Esperanto. On August 9, 1905, it was made the only obligatory authority over the language by the Declaration of Boulogne at the first World Esperanto Congress. Much of the content of the book is a reproduction of content from Zamenhof's earlier works, particularly Unua Libro.

Finvenkismo is an ideological current within the Esperanto movement. The name is derived from the concept of a fina venko, denoting the moment when Esperanto will be used as the predominant second language throughout the world. A finvenkist is thus someone who hopes for or works towards this "final victory" of Esperanto. According to some finvenkists, this "final victory" of Esperanto may help eradicate war, chauvinism, and cultural oppression. The exact nature of this adoption, and what would constitute a "final victory" is often left unspecified.

Homaranismo is a philosophy developed by L. L. Zamenhof, who laid the foundations of the Esperanto language. Based largely on the teachings of Hillel the Elder, Zamenhof originally called it Hillelism. He sought to reform Judaism because he hoped that without the strict dress code and purity requirements, it would no longer be the victim of antisemitic propaganda. The basis of Homaranismo is the sentence known as the Golden Rule: One should treat others as one would like others to treat oneself.

Dua Libro de l' Lingvo Internacia, usually referred to simply as Dua Libro, is an 1888 book by L. L. Zamenhof. It is the second book in which Zamenhof wrote about the constructed language Esperanto, following Unua Libro in 1887, and the first book to be written entirely in the language.

Louis-Christophe Zaleski-Zamenhof was a Polish-born French civil and marine engineer, specializing in the design of structural steel and concrete construction. He was a grandson of the Polish Jewish L. L. Zamenhof, the inventor of the international auxiliary language Esperanto. From the 1960s until his death, Zaleski-Zamenhof lived in France.

La Esperantisto, stylised as La Esperantisto., was the first Esperanto periodical, published from 1889 to 1895. L. L. Zamenhof started it in order to provide reading material for the then-nascent Esperanto community.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Esperanto:

Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language is a 2016 non-fiction book by American poet and professor Esther Schor. Concerning the history of Esperanto, the world's most widely spoken constructed language, it looks at various figures within Esperanto's history as well as Schor's own experiences with the language as an Esperantist.