Source amnesia is the inability to remember where, when or how previously learned information has been acquired, while retaining the factual knowledge. This branch of amnesia is associated with the malfunctioning of one's explicit memory. It is likely that the disconnect between having the knowledge and remembering the context in which the knowledge was acquired is due to a dissociation between semantic and episodic memory – an individual retains the semantic knowledge, but lacks the episodic knowledge to indicate the context in which the knowledge was gained.

Cognitive neuropsychology is a branch of cognitive psychology that aims to understand how the structure and function of the brain relates to specific psychological processes. Cognitive psychology is the science that looks at how mental processes are responsible for the cognitive abilities to store and produce new memories, produce language, recognize people and objects, as well as our ability to reason and problem solve. Cognitive neuropsychology places a particular emphasis on studying the cognitive effects of brain injury or neurological illness with a view to inferring models of normal cognitive functioning. Evidence is based on case studies of individual brain damaged patients who show deficits in brain areas and from patients who exhibit double dissociations. Double dissociations involve two patients and two tasks. One patient is impaired at one task but normal on the other, while the other patient is normal on the first task and impaired on the other. For example, patient A would be poor at reading printed words while still being normal at understanding spoken words, while the patient B would be normal at understanding written words and be poor at understanding spoken words. Scientists can interpret this information to explain how there is a single cognitive module for word comprehension. From studies like these, researchers infer that different areas of the brain are highly specialised. Cognitive neuropsychology can be distinguished from cognitive neuroscience, which is also interested in brain-damaged patients, but is particularly focused on uncovering the neural mechanisms underlying cognitive processes.

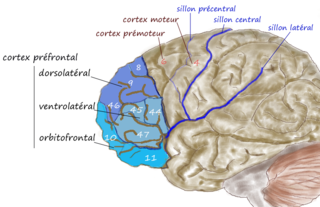

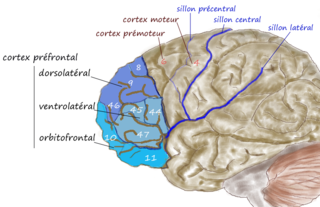

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere. It is parted from the parietal lobe by a groove between tissues called the central sulcus and from the temporal lobe by a deeper groove called the lateral sulcus. The most anterior rounded part of the frontal lobe is known as the frontal pole, one of the three poles of the cerebrum.

Brodmann area 9, or BA9, refers to a cytoarchitecturally defined portion of the frontal cortex in the brain of humans and other primates. Its cytoarchitecture is referred to as granular due to the concentration of granule cells in layer IV. It contributes to the dorsolateral and medial prefrontal cortex.

The Levels of Processing model, created by Fergus I. M. Craik and Robert S. Lockhart in 1972, describes memory recall of stimuli as a function of the depth of mental processing. More analysis produce more elaborate and stronger memory than lower levels of processing. Depth of processing falls on a shallow to deep continuum. Shallow processing leads to a fragile memory trace that is susceptible to rapid decay. Conversely, deep processing results in a more durable memory trace. There are three levels of processing in this model. Structural processing, or visual, is when we remember only the physical quality of the word E.g how the word is spelled and how letters look. Phonemic processing includes remembering the word by the way it sounds. E.G the word tall rhymes with fall. Lastly, we have semantic processing in which we encode the meaning of the word with another word that is similar or has similar meaning. Once the word is perceived, the brain allows for a deeper processing.

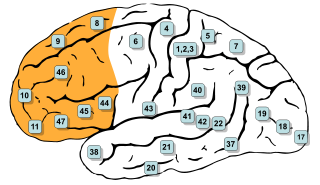

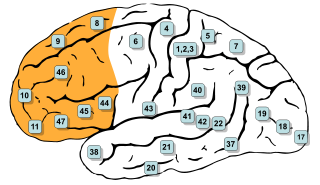

In mammalian brain anatomy, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. It is the association cortex in the frontal lobe. The PFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA11, BA12, BA13, BA14, BA24, BA25, BA32, BA44, BA45, BA46, and BA47.

In cognitive science and neuropsychology, executive functions are a set of cognitive processes that are necessary for the cognitive control of behavior: selecting and successfully monitoring behaviors that facilitate the attainment of chosen goals. Executive functions include basic cognitive processes such as attentional control, cognitive inhibition, inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Higher-order executive functions require the simultaneous use of multiple basic executive functions and include planning and fluid intelligence.

Frontal lobe disorder, also frontal lobe syndrome, is an impairment of the frontal lobe of the brain due to disease or frontal lobe injury. The frontal lobe plays a key role in executive functions such as motivation, planning, social behaviour, and speech production. Frontal lobe syndrome can be caused by a range of conditions including head trauma, tumours, neurodegenerative diseases, neurodevelopmental disorders, neurosurgery and cerebrovascular disease. Frontal lobe impairment can be detected by recognition of typical signs and symptoms, use of simple screening tests, and specialist neurological testing.

Utilization behavior (UB) is a type of neurobehavioral phenomena that involves someone grabbing objects in view and starting the 'appropriate' behavior associated with it at an 'inappropriate' time. Patients exhibiting utilization behavior have difficulty resisting the impulse to operate or manipulate objects which are in their visual field and within reach. Characteristics of UB include unintentional, unconscious actions triggered by the immediate environment. The unpreventable excessive behavior has been linked to lesions in the frontal lobe. UB has also been referred to as "bilateral magnetic apraxia" and "hypermetamorphosis".

Fergus Ian Muirden Craik FRS is a cognitive psychologist known for his research on levels of processing in memory. This work was done in collaboration with Robert Lockhart at the University of Toronto in 1972 and continued with another collaborative effort with Endel Tulving in 1975. Craik has received numerous awards and is considered a leader in the area of memory, attention and cognitive aging. Moreover, his work over the years can be seen in developmental psychology, aging and memory, and the neuropsychology of memory.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is an area in the prefrontal cortex of the primate brain. It is one of the most recently derived parts of the human brain. It undergoes a prolonged period of maturation which lasts into adulthood. The DLPFC is not an anatomical structure, but rather a functional one. It lies in the middle frontal gyrus of humans. In macaque monkeys, it is around the principal sulcus. Other sources consider that DLPFC is attributed anatomically to BA 9 and 46 and BA 8, 9 and 10.

The frontal lobe of the human brain is both relatively large in mass and less restricted in movement than the posterior portion of the brain. It is a component of the cerebral system, which supports goal directed behavior. This lobe is often cited as the part of the brain responsible for the ability to decide between good and bad choices, as well as recognize the consequences of different actions. Because of its location in the anterior part of the head, the frontal lobe is arguably more susceptible to injuries. Following a frontal lobe injury, an individual's abilities to make good choices and recognize consequences are often impaired. Memory impairment is another common effect associated with frontal lobe injuries, but this effect is less documented and may or may not be the result of flawed testing. Damage to the frontal lobe can cause increased irritability, which may include a change in mood and an inability to regulate behavior. Particularly, an injury of the frontal lobe could lead to deficits in executive function, such as anticipation, goal selection, planning, initiation, sequencing, monitoring, and self-correction. A widely reported case of frontal lobe injury was that of Phineas Gage, a railroad worker whose left frontal lobe was damaged by a large iron rod in 1848.

Retrospective memory is the memory of people, words, and events encountered or experienced in the past. It includes all other types of memory including episodic, semantic and procedural. It can be either implicit or explicit. In contrast, prospective memory involves remembering something or remembering to do something after a delay, such as buying groceries on the way home from work. However, it is very closely linked to retrospective memory, since certain aspects of retrospective memory are required for prospective memory.

Cognitive planning is one of the executive functions. It encompasses the neurological processes involved in the formulation, evaluation and selection of a sequence of thoughts and actions to achieve a desired goal. Various studies utilizing a combination of neuropsychological, neuropharmacological and functional neuroimaging approaches have suggested there is a positive relationship between impaired planning ability and damage to the frontal lobe.

In psychology, confabulation is a memory error consisting of the production of fabricated, distorted, or misinterpreted memories about oneself or the world. It is generally associated with certain types of brain damage or a specific subset of dementias. While still an area of ongoing research, the basal forebrain is implicated in the phenomenon of confabulation. People who confabulate present with incorrect memories ranging from subtle inaccuracies to surreal fabrications, and may include confusion or distortion in the temporal framing of memories. In general, they are very confident about their recollections, even when challenged with contradictory evidence.

Executive functions are a cognitive apparatus that controls and manages cognitive processes. Norman and Shallice (1980) proposed a model on executive functioning of attentional control that specifies how thought and action schemata become activated or suppressed for routine and non-routine circumstances. Schemas, or scripts, specify an individual's series of actions or thoughts under the influence of environmental conditions. Every stimulus condition turns on the activation of a response or schema. The initiation of appropriate schema under routine, well-learned situations is monitored by contention scheduling which laterally inhibits competing schemas for the control of cognitive apparatus. Under unique, non-routine procedures controls schema activation. The SAS is an executive monitoring system that oversees and controls contention scheduling by influencing schema activation probabilities and allowing for general strategies to be applied to novel problems or situations during automatic attentional processes.

Ian Robertson is a Scottish neuroscientist and clinical psychologist, and Professor of Psychology at Trinity College Dublin. He is also known as a leading researcher as to how an individual may harness the attention system of one's mind to enhance autonomy over emotions and cognitive function.

Hypofrontality is a state of decreased cerebral blood flow (CBF) in the prefrontal cortex of the brain. Hypofrontality is symptomatic of several neurological medical conditions, such as schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. This condition was initially described by Ingvar and Franzén in 1974, through the use of xenon blood flow technique with 32 detectors to image the brains of patients with schizophrenia. This finding was confirmed in subsequent studies using the improved spatial resolution of positron emission tomography with the fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) tracer. Subsequent neuroimaging work has shown that the decreases in prefrontal CBF are localized to the medial, lateral, and orbital portions of the prefrontal cortex. Hypofrontality is thought to contribute to the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

The anti-saccade (AS) task is a way of measuring how well the frontal lobe of the brain can control the reflexive saccade, or eye movement. Saccadic eye movement is primarily controlled by the frontal cortex.

Antoine Bechara is an American neuroscientist, academic and researcher. He is currently a professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of Southern California.