Transport economics is a branch of economics founded in 1959 by American economist John R. Meyer that deals with the allocation of resources within the transport sector. It has strong links to civil engineering. Transport economics differs from some other branches of economics in that the assumption of a spaceless, instantaneous economy does not hold. People and goods flow over networks at certain speeds. Demands peak. Advance ticket purchase is often induced by lower fares. The networks themselves may or may not be competitive. A single trip may require the bundling of services provided by several firms, agencies and modes.

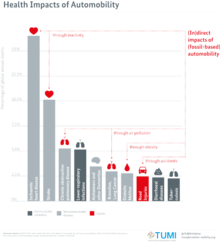

In economics, an externality or external cost is an indirect cost or benefit to an uninvolved third party that arises as an effect of another party's activity. Externalities can be considered as unpriced components that are involved in either consumer or producer market transactions. Air pollution from motor vehicles is one example. The cost of air pollution to society is not paid by either the producers or users of motorized transport to the rest of society. Water pollution from mills and factories is another example. All (water) consumers are made worse off by pollution but are not compensated by the market for this damage. A positive externality is when an individual's consumption in a market increases the well-being of others, but the individual does not charge the third party for the benefit. The third party is essentially getting a free product. An example of this might be the apartment above a bakery receiving some free heat in winter. The people who live in the apartment do not compensate the bakery for this benefit.

An environmental tax, ecotax, or green tax is a tax levied on activities which are considered to be harmful to the environment and is intended to promote environmentally friendly activities via economic incentives. One notable example is a carbon tax. Such a policy can complement or avert the need for regulatory approaches. Often, an ecotax policy proposal may attempt to maintain overall tax revenue by proportionately reducing other taxes ; such proposals are known as a green tax shift towards ecological taxation. Ecotaxes address the failure of free markets to consider environmental impacts.

Road pricing are direct charges levied for the use of roads, including road tolls, distance or time-based fees, congestion charges and charges designed to discourage the use of certain classes of vehicle, fuel sources or more polluting vehicles. These charges may be used primarily for revenue generation, usually for road infrastructure financing, or as a transportation demand management tool to reduce peak hour travel and the associated traffic congestion or other social and environmental negative externalities associated with road travel such as air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, visual intrusion, noise pollution and road traffic collisions.

Congestion pricing or congestion charges is a system of surcharging users of public goods that are subject to congestion through excess demand, such as through higher peak charges for use of bus services, electricity, metros, railways, telephones, and road pricing to reduce traffic congestion; airlines and shipping companies may be charged higher fees for slots at airports and through canals at busy times. Advocates claim this pricing strategy regulates demand, making it possible to manage congestion without increasing supply.

Since the start of the twentieth century, the role of cars has become highly important, though controversial. They are used throughout the world and have become the most popular mode of transport in many of the more developed countries. In developing countries cars are fewer and the effects of the car on society are less visible, however they are nonetheless significant. The spread of cars built upon earlier changes in transport brought by railways and bicycles. They introduced sweeping changes in employment patterns, social interactions, infrastructure and the distribution of goods.

A Pigouvian tax is a tax on any market activity that generates negative externalities. A Pigouvian tax is a method that tries to internalize negative externalities to achieve the Nash equilibrium and optimal Pareto efficiency. The tax is normally set by the government to correct an undesirable or inefficient market outcome and does so by being set equal to the external marginal cost of the negative externalities. In the presence of negative externalities, social cost includes private cost and external cost caused by negative externalities. This means the social cost of a market activity is not covered by the private cost of the activity. In such a case, the market outcome is not efficient and may lead to over-consumption of the product. Often-cited examples of negative externalities are environmental pollution and increased public healthcare costs associated with tobacco and sugary drink consumption.

Vehicle emissions control is the study of reducing the emissions produced by motor vehicles, especially internal combustion engines. The primary emissions studied include hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and sulfur oxides. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, various regulatory agencies were formed with a primary focus on studying the vehicle emissions and their effects on human health and the environment. As the worlds understanding of vehicle emissions improved, so did the devices used to mitigate their impacts. The regulatory requirements of the Clean Air Act, which was amended many times, greatly restricted acceptable vehicle emissions. With the restrictions, vehicles started being designed more efficiently by utilizing various emission control systems and devices which became more common in vehicles over time.

Exhaust gas or flue gas is emitted as a result of the combustion of fuels such as natural gas, gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, fuel oil, biodiesel blends, or coal. According to the type of engine, it is discharged into the atmosphere through an exhaust pipe, flue gas stack, or propelling nozzle. It often disperses downwind in a pattern called an exhaust plume.

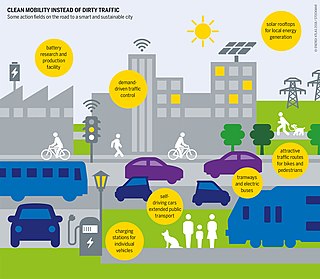

Sustainable transport refers to ways of transportation that are sustainable in terms of their social and environmental impacts. Components for evaluating sustainability include the particular vehicles used for road, water or air transport; the source of energy; and the infrastructure used to accommodate the transport. Transport operations and logistics as well as transit-oriented development are also involved in evaluation. Transportation sustainability is largely being measured by transportation system effectiveness and efficiency as well as the environmental and climate impacts of the system. Transport systems have significant impacts on the environment, accounting for between 20% and 25% of world energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions. The majority of the emissions, almost 97%, came from direct burning of fossil fuels. In 2019, about 95% of the fuel came from fossil sources. The main source of greenhouse gas emissions in the European Union is transportation. In 2019 it contributes to about 31% of global emissions and 24% of emissions in the EU. In addition, up to the COVID-19 pandemic, emissions have only increased in this one sector. Greenhouse gas emissions from transport are increasing at a faster rate than any other energy using sector. Road transport is also a major contributor to local air pollution and smog.

A green vehicle, clean vehicle, eco-friendly vehicle or environmentally friendly vehicle is a road motor vehicle that produces less harmful impacts to the environment than comparable conventional internal combustion engine vehicles running on gasoline or diesel, or one that uses certain alternative fuels. Presently, in some countries the term is used for any vehicle complying or surpassing the more stringent European emission standards, or California's zero-emissions vehicle standards, or the low-carbon fuel standards enacted in several countries.

Transportation demand management or travel demand management (TDM) is the application of strategies and policies to increase the efficiency of transportation systems, that reduce travel demand, or to redistribute this demand in space or in time.

Motoring taxation in the United Kingdom consists primarily of vehicle excise duty, which is levied on vehicles registered in the UK, and hydrocarbon oil duty, which is levied on the fuel used by motor vehicles. VED and fuel tax raised approximately £32 billion in 2009, a further £4 billion was raised from the value added tax on fuel purchases. Motoring-related taxes for fiscal year 2011/12, including fuel duties and VED, are estimated to amount to more than £38 billion, representing almost 7% of total UK taxation.

Compared to other popular modes of passenger transportation, the car has a relatively high cost per person-distance traveled. The income elasticity for cars ranges from very elastic in poor countries, to inelastic in rich nations. The advantages of car usage include on-demand and door-to-door travel, and are not easily substituted by cheaper alternative modes of transport, with the present level and type of auto specific infrastructure in the countries with high auto usage.

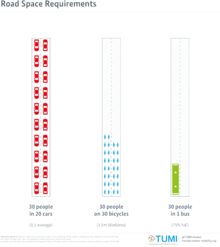

Car dependency is a phenomenon in urban planning wherein existing and planned infrastructure prioritizes the use of automobiles over other modes of transportation, such as public transit, bicycles, and walking.

A car, or an automobile, is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of cars state that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport people over cargo. There are around one billion cars in use worldwide. The car is considered an essential part of the developed economy.

The environmental impact of transport are significant because transport is a major user of energy, and burns most of the world's petroleum. This creates air pollution, including nitrous oxides and particulates, and is a significant contributor to global warming through emission of carbon dioxide. and also plant pollution, by heavy metals. Within the transport sector, road transport is the largest contributor to global warming.

Mobile source air pollution includes any air pollution emitted by motor vehicles, airplanes, locomotives, and other engines and equipment that can be moved from one location to another. Many of these pollutants contribute to environmental degradation and have negative effects on human health. To prevent unnecessary damage to human health and the environment, environmental regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have established policies to minimize air pollution from mobile sources. Similar agencies exist at the state level. Due to the large number of mobile sources of air pollution, and their ability to move from one location to another, mobile sources are regulated differently from stationary sources, such as power plants. Instead of monitoring individual emitters, such as an individual vehicle, mobile sources are often regulated more broadly through design and fuel standards. Examples of this include corporate average fuel economy standards and laws that ban leaded gasoline in the United States. The increase in the number of motor vehicles driven in the U.S. has made efforts to limit mobile source pollution challenging. As a result, there have been a number of different regulatory instruments implemented to reach the desired emissions goals.

Air pollution in India is a serious environmental issue. Of the 30 most polluted cities in the world, 21 were in India in 2019. As per a study based on 2016 data, at least 140 million people in India breathe air that is 10 times or more over the WHO safe limit and 13 of the world's 20 cities with the highest annual levels of air pollution are in India. 51% of the pollution is caused by industrial pollution, 27% by vehicles, 17% by crop burning and 5% by other sources. Air pollution contributes to the premature deaths of 2 million Indians every year. Emissions come from vehicles and industry, whereas in rural areas, much of the pollution stems from biomass burning for cooking and keeping warm. In autumn and spring months, large scale crop residue burning in agriculture fields – a cheaper alternative to mechanical tilling – is a major source of smoke, smog and particulate pollution. India has a low per capita emissions of greenhouse gases but the country as a whole is the third largest greenhouse gas producer after China and the United States. A 2013 study on non-smokers has found that Indians have 30% weaker lung function than Europeans.

Road ecology is the study of the ecological effects of roads and highways. These effects may include local effects, such as on noise, water pollution, habitat destruction/disturbance and local air quality; and the wider environmental effects of transport such as habitat fragmentation, ecosystem degradation, and climate change from vehicle emissions.