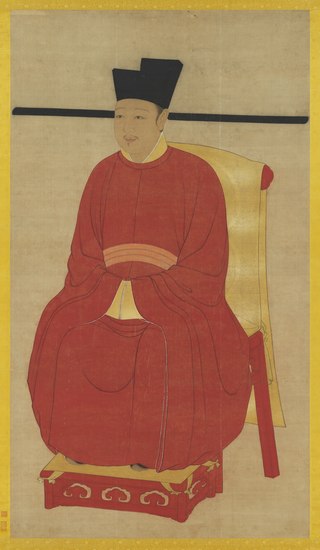

| Emperor Shenzong of Song 宋神宗 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Song dynasty | |||||||||||||

| Reign | 25 January 1067 – 1 April 1085 | ||||||||||||

| Coronation | 25 January 1067 | ||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Emperor Yingzong | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Emperor Zhezong | ||||||||||||

| Born | Zhao Zhongzhen (1048–1067) Zhao Xu (1067–1085) 25 May 1048 | ||||||||||||

| Died | 1 April 1085 (aged 36) | ||||||||||||

| Burial | Yongyu Mausoleum (永裕陵, in present-day Gongyi, Henan) | ||||||||||||

| Consorts | |||||||||||||

| Issue | Emperor Zhezong Zhao Bi Emperor Huizong Zhao Yu Zhao Shi Zhao Cai Princess Xianmu Princess Xianxiao Princess Xianjing | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| House | Zhao | ||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Song (Northern Song) | ||||||||||||

| Father | Emperor Yingzong | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Xuanren | ||||||||||||

The Emperor Shenzong of Song (25 May 1048 – 1 April 1085), personal name Zhao Xu, was the sixth emperor of the Song dynasty of China. His original personal name was Zhao Zhongzhen but he changed it to "Zhao Xu" after he acceded to the throne. He reigned from 1067 until his death in 1085 and is best known for supporting Wang Anshi's New Policies. He was a particularly active monarch concerned with solving the fiscal, bureaucratic, and military problems of the Song dynasty, but his reign remains controversial.

Contents

- Reign

- Personality

- Muslim mercenaries

- Wang Anshi's New Policies

- Personal involvement in the New Policies

- Yuanfeng Reforms

- Campaign against Vietnam

- Embassy from the Byzantine Empire

- Campaign against the Western Xia dynasty

- Zizhi Tongjian and other literary works

- Death and legacy

- Family

- Ancestry

- See also

- References

- Citations

- Bibliography

Reign

Personality

Emperor Shenzong disagreed with the passive stance of his predecessors and wanted to improve the Song Dynasty's prestige via conquest. This irridentist attitude also contributed towards his desire to centralize fiscal matters: he told his war minister Wen Yanbo that "if we are to raise troops for our frontier campaigns, then our treasuries must be full." [1] Furthermore, Shenzong was dissatisfied with the growing powers of ministers such as chief councilor Han Chi. Shenzong's goals were opposed by the conservatives, particularly Fu Bi and Sima Guang, who were concerned with his expansion of monarchical power and who wanted to maintain the peaceful equilibrium with the Western Xia and the Liao Dynasty. Shenzong respected the conservative faction: he kept Fu Bi in the capital until 1072 and had close relations with Sima Guang, whom he admired for his morality and intelligence. [2]

Muslim mercenaries

Emperor Shenzong hired Muslim warriors from Bukhara to fight against the Khitan Liao dynasty. 5,300 Muslim men from Bukhara were encouraged and invited to move to China in 1070 by Shenzong to help battle the Liao empire in the northeast and repopulate areas ravaged by fighting. [3] The emperor hired these men as mercenaries in his campaign against the Liao dynasty. Later on, these men were settled between the Song capital of Bianliang (today Kaifeng) and Yenching (modern Beijing). The circuits (道) of the north and northeast were settled in 1080 when 10,000 more Muslims were invited into China. [3] [4]

Wang Anshi's New Policies

During his reign in 1068, Emperor Shenzong became interested in Wang Anshi's policies and appointed Wang as the Chancellor. Wang implemented his famous New Policies aimed at improving the situation for the peasantry and unemployed. These acts became the hallmark reform of Emperor Shenzong's reign.

Before Shenzong took the throne in 1067, there was pressure on the Song dynasty to make economic reforms. The Song dynasty's rigorous civil service examinations rejuvenated humanist-oriented Confucian elite culture; in particular, the literati wanted to improve the material conditions of the people. Additionally, the humiliating loss against the Western Xia in the 1040s [5] (as well as the unfavorable terms of the Treaty of Chanyuan) created, according to Sogabe Shizuo, a "perpetual wartime fiscal regime". [6] Shenzong was particularly driven by his irridentist determination to recover the Sixteen Prefectures. [7]

Immediately after taking the throne in 1067, Emperor Shenzong established the Office of Expenditure Reduction with Sima Guang at its head to improve Song finances. Sima refused and instead issued a scathing report discussing the immensity of the dynasty's financial problems. [8] Indeed, defense consumed 83% of the dynasty's cash income, while the expanding and already-large bureaucracy was very costly to maintain. [9] In 1069, after failing again to gain support for reform from the official Fu Bi, [10] Shenzong made Wang Anshi the head of government and supported his consolidation of power and his New Policies. [11]

Personal involvement in the New Policies

Shenzong largely delegated authority to Wang until his retirement in 1076. An exception was when Shenzong advised Wang Anshi and Chen Shengzhi in early winter 1069 to abandon the Finance Planning Commission (which Wang had set up earlier that year) and instead rely on their power as Secretariats to manage the economy. Wang refused, reasoning that the Commission was needed to coordinate fiscal matters between the Secretariat and the Military Affairs Commission. He rejected Shenzong's proposal to have Wang head the Commission himself on the same grounds. [12] In another instance, Shenzong proposed the restoration of the equal-field system (a system of land redistribution instated by the Northern Wei and used through the Tang dynasty), but Wang Anshi dismissed the idea as impractical. [5] Shenzong's fascination with the revenue-generating potential of interest prompted him to invest heavily in a new price control policy, despite complaints from merchants and consumers about governmental harassment. [13]

Shenzong and Wang Anshi also pursued direct military reforms. In theory, each commandery was 500 troops strong, but in actuality, the number was much lower and contained many old or weak soldiers due to corruption. Shenzong cut down the number of excess troops so that the entire army was less than 900,000 strong and established the Area Generalship System to improve communications, discipline, and troop levy efficiency. Meanwhile, the Baojia system was introduced as a village defense system intended to bolster domestic security and provide further support to the regular army. [14]

Though the New Policies gave Shenzong a large budget surplus, they failed to achieve their goal of improving the Song dynasty's military. The Western Xia continued to inflict defeats on the Song and an attack on the Liao dynasty remained unthinkable. [11] This was caused by continually low army quality, poor logistics, and overall poor leadership. The Baojia system, for example, did not produce troops capable enough to replace the imperial army. [15] The military failures of the Reforms, to which Shenzong had devoted immense amounts of energy, contributed to his eventual illness and death. [14] The New Policies' circumvention of checks on central power was controversial from the onset; both Fu Bi and Sima Guang wrote memorials to Shenzong advising him to balance governmental function, respect the bureaucratic process, and not to support Wang Anshi. [16]

Yuanfeng Reforms

In 1074, a severe drought afflicted Northern China. Many officials such as Han Wei thought that this was heaven’s punishment for instating the New Policies. This, along with the general controversy surrounding the New Polices and Wang’s own misbehavior regarding court factions prompted Shenzong to remove him from his post as chief minister in 1074. Shenzong nonetheless remained on the side of the reformers and retained Wang as a mentor. Lü Huiqing, a reformer, gained Shenzong’s favor and harshly opposed Wang while building up his own power base. His own misbehavior broke up the reformist coalition and Wang was recalled to the capital to replace Lü. Wang did not stay for long and an astronomical omen (along with further misbehavior such as pretending to be sick and overworking his son to death) prompted the distraught man’s permanent retirement in 1076. [17]

Following Wang Anshi's permanent retirement in 1076, Shenzong took personal control of the reform agenda and launched the Yuanfeng Reforms. He first significantly expanded his personal power and used the domineering official Cai Jue to keep the conservatives, many of whom had been invited back to court, in line with the emperor. [18] In 1082, Shenzong restructured the bureaucracy and restored the Tang model of a central government organized around the Six Ministries by creating the Secretariat, Chancellery, and Department of State Affairs to balance the departments against each other. However, due to design flaws, the Secretariat quickly came to dominate the other two departments. [19] Moreover, the strict division of the bureaucracy, in which every policy initiative had to take a complicated route to be approved, was inefficient. With Shenzong himself as the most active policy maker, this inefficiency was largely unproblematic, but the reigns of the child-emperor Zhezong and the incompetent emperor Huizong exposed the redundancy of such a system. [20]

The Finance Commission and Exchequer of Imperial Lands (institutions that predated the New Policies) were dissolved and replaced by the Ministry of Revenue. Shenzong made the Yuanfeng Treasury to raise funds for a renewed offensive against the Western Xia; although the offensive was defeated, the Treasury remained as a depository for revenues from both the New Policies and state-run monopolies. Both the Ministry of Revenue and the Yuanfeng Treasury exercised substantial control over Song fiscal resources. [21] The Yuanfeng Reforms were likely inspired by institutional reform proposals made during the reign of Emperor Renzong of Song and a concern towards the growing power of the Chief counsilorship, but the reforms' rigidity likely contributed to the autocratic nature of the later dynasty. [22] Unlike the New Policies, the Yuanfeng Reforms likely escaped the conservative anti-reform movement headed by Sima Guang and Grand Dowager Empress Xuanren due to their Tang inspiration and Shenzong's hand in heading them. [23]

Campaign against Vietnam

Emperor Shenzong sent campaigns against the Vietnamese ruler Lý Nhân Tông of the Lý dynasty in 1076. [24]

Embassy from the Byzantine Empire

Aside from the ancient Roman embassies to Han and Three-Kingdoms era China, contact with Europe remained sparse if not nonexistent before the 13th century. However, from Chinese records it is known that Michael VII Doukas (Mie li yi ling kai sa 滅力伊靈改撒) of Fo lin (i.e. the Byzantine Empire) dispatched a diplomatic mission to China's Song dynasty that arrived in 1081, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong. [25]

Campaign against the Western Xia dynasty

Emperor Shenzong's other notable act as emperor was his attempt to weaken the Tangut-led Western Xia state by invading and expelling the Western Xia forces from Qing prefecture (庆州, today Qingyang, Gansu Province). The Song army was initially quite successful in these campaigns, but during the battle for the city of Yongle (永乐城), in 1082, Song forces were defeated. As a result, Western Xia grew more powerful and subsequently continued to be a thorn in the side of the Song Empire over the ensuing decades.

Zizhi Tongjian and other literary works

Sima Guang, a minister interested in the history of the previous 1000 years, published the Zizhi Tongjian or A Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government in 1084. This book records historical events from the Zhou dynasty to the Song dynasty. Another notable literary achievement that occurred during his reign was the compilation of the Seven Military Classics, including the alleged forgery of the Questions and Replies between Tang Taizong and Li Weigong. [26]

Death and legacy

The disastrous defeat at the battle of Yongle City in 1082 during the Song invasion of Western Xia completely broke Shenzong’s spirit. In tears, he berated his councilors and said “Not a single one of you said that the [Yongle City] campaign was wrong.” [27] He was crushed by the realization that his reforms, into which he had poured immense amounts of time and energy, had failed. [14] Accordingly, his reformist zeal slowed down and he increasingly favored the conservatives, particularly Sima Guang. In Autumn 1084, Shenzong sensed he was dying and entrusted the heir to Sima Guang and Lü Gongzhu.

Emperor Shenzong died in early 1085 at the age of 36 from an unspecified illness and was succeeded by his son, Zhao Xu who took the throne as Emperor Zhezong. Emperor Zhezong was underage and so Shenzong’s mother Empress Gao ruled as regent until her death. A political struggled ensued following Shenzong’s death. The Emperss Dowager’s conservative faction (which included Sima Guang, Lü Gongzhu, the famous poet Su Shi, and the co-founder of Neo-confucianism, Cheng Hao) defeated Cai Jue’s faction. The conservatives went on to repeal the New Polices and purge the court of remaining reformers. [28]

Family

Consorts and Issue:

- Empress Qinsheng, of the Xiang clan (欽聖皇后 向氏; 1046–1101)

- Princess Shuhuai (淑懷帝姬; 1067–1078), 1st daughter

- Empress Qincheng, of the Zhu clan (欽成皇后 朱氏; 1052–1102)

- Zhao Xu, Zhezong (哲宗 趙煦; 1077–1100), 6th son

- Zhao Shi, Prince Churongxian (楚榮憲王 趙似; 1083–1106), 13th son

- Princess Xianjing (賢靜帝姬; 1085–1115), 10th daughter

- Married Pan Yi (潘意) in 1104, and had issue (two sons)

- Empress Qinci, of the Chen clan (欽慈皇后 陳氏; 1058–1089)

- Zhao Ji, Huizong (徽宗 趙佶; 1082–1135), 11th son

- Noble Consort Yimu, of the Xing clan (懿穆貴妃 邢氏; d. 1103)

- Zhao Jin, Prince Hui (惠王 趙僅; 1071), 2nd son

- Zhao Xian, Prince Ji (冀王 趙僩; 1074–1076), 5th son

- Zhao Jia, Prince Yudaohui (豫悼惠王 趙價; 1077–1078), 7th son

- Zhao Ti, Prince Xuchonghui (徐沖惠王 趙倜; 1078–1081), 8th son

- Noble Consort, of the Yang clan (懿靜貴妃 楊氏)

- Noble Consort, of the Song clan (貴妃 宋氏; d. 1117)

- Zhao Yi, Prince Cheng (成王 趙佾; 1069), 1st son

- Zhao Jun, Prince Tang'aixian (唐哀獻王 趙俊; 1073–1077), 3rd son

- Princess Xianxiao (賢孝帝姬; d. 1108), 4th daughter

- Married Wang Yu (王遇) in 1097

- Pure Consort, of the Zhang clan (懿靜淑妃 張氏; d. 1105)

- Princess Xianke (賢恪帝姬; d. 1072), 2nd daughter

- Virtuous Consort, of the Zhu clan (德妃 朱氏)

- Princess Xianmu (賢穆帝姬; d. 1084)

- Able Consort, of the Wu clan (惠穆賢妃 武氏; d. 1107)

- Zhao Bi, Prince Wurongmu (吳榮穆王 趙佖; 1082–1106), 9th son

- Princess Xianhe (賢和帝姬; d. 1090)

- Able Consort, of the Lin clan (賢妃 林氏; 1052–1090), personal name Zhen (貞)

- Zhao Yu, Prince Yan (燕王 趙俁; 1083–1127), 12th son

- Princess Xianling (賢令帝姬; d. 1084), 7th daughter

- Zhao Cai, Prince Yue (越王 趙偲; 1085–1129), 14th son

- Cairen, of the Guo clan (才人 郭氏)

- Zhao Wei, Prince Yi (儀王 趙偉; 1082), 10th son

- Furen, of the Xiang clan (夫人 向氏)

- Zhao Shen, Prince Bao (褒王 趙伸; 1074), 4th son

- Unknown

- Princess Xianmu (賢穆帝姬; d. 1111), 3rd daughter

- Married Han Jiayan (韓嘉彥; d. 1129)

- Princess Xiankang (賢康帝姬; d. 1085)

- Princess Xianyi (賢宜帝姬; d. 1085)

- Princess Xianmu (賢穆帝姬; d. 1111), 3rd daughter

Ancestry

| Emperor Shenzong of Song | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 宋神宗 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | "Spiritual Ancestor of the Song" | ||||||

| |||||||

| Zhao Yuanfen (969–1005) | |||||||||||||||

| Zhao Yunrang (995–1059) | |||||||||||||||

| Lady Li | |||||||||||||||

| Emperor Yingzong of Song (1032–1067) | |||||||||||||||

| Ren Gu | |||||||||||||||

| Lady Ren | |||||||||||||||

| Lady Zhang | |||||||||||||||

| Emperor Shenzong of Song (1048–1085) | |||||||||||||||

| Gao Jixun (959–1036) | |||||||||||||||

| Gao Zunfu | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Xuanren (1032–1093) | |||||||||||||||

| Cao Qi | |||||||||||||||

| Lady Cao | |||||||||||||||

| Lady Feng | |||||||||||||||