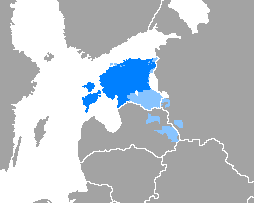

Estonian is a Finnic language and the official language of Estonia. It is written in the Latin script, and is the first language of the majority of the country's population; it is also an official language of the European Union. Estonian is spoken natively by about 1.1 million people; 922,000 people in Estonia, and 160,000 elsewhere.

Romantic nationalism is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes such factors as language, race, ethnicity, culture, religion, and customs of the nation in its primal sense of those who were born within its culture. It can be applied to ethnic nationalism as well as civic nationalism. Romantic nationalism arose in reaction to dynastic or imperial hegemony, which assessed the legitimacy of the state from the top down, emanating from a monarch or other authority, which justified its existence. Such downward-radiating power might ultimately derive from a god or gods (see the divine right of kings and the Mandate of Heaven).

Kalevipoeg is a 19th century epic poem by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald which has since been considered the Estonian national epic.

Nordic folk music includes a number of traditions of Nordic countries, especially Scandinavian. The Nordic countries are Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland.

Johann Gottfried von Herder was a German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He is associated with the Enlightenment, Sturm und Drang, and Weimar Classicism. He was a Romantic philosopher and poet who argued that true German culture was to be discovered among the common people. He also stated that it was through folk songs, folk poetry, and folk dances that the true spirit of the nation was popularized.

Lydia Emilie Florentine Jannsen, known by her pen name Lydia Koidula, was an Estonian poet. Her sobriquet means 'Lydia of the Dawn' in Estonian. It was given to her by the writer Carl Robert Jakobson. She is also frequently referred to as Koidulaulik – 'Singer of the Dawn'.

Estonian mythology is a complex of myths belonging to the Estonian folk heritage and literary mythology. Information about the pre-Christian and medieval Estonian mythology is scattered in historical chronicles, travellers' accounts and in ecclesiastical registers. Systematic recordings of Estonian folklore started in the 19th century. Pre-Christian Estonian deities may have included a god known as Jumal or Taevataat in Estonian, corresponding to Jumala in Finnish, and Jumo in Mari.

Lāčplēsis is an epic poem by Andrejs Pumpurs, a Latvian poet, who wrote it between 1872 and 1887 based on local legends. It is set during the Livonian Crusades telling the story of the mythical hero Lāčplēsis "the Bear Slayer". Lāčplēsis is regarded as the Latvian national epic.

The Estonian Age of Awakening is a period in history where Estonians came to acknowledge themselves as a nation deserving the right to govern themselves. This period is considered to begin in the 1850s with greater rights being granted to commoners and to end with the declaration of the Republic of Estonia in 1918. The term is sometimes also applied to the period around 1987 and 1988.

Otto Wilhelm Masing was a clergyman, writer, journalist, linguist, notable early Estophile and a major advocate of Estonian commoners' rights, especially regarding education.

The culture of Estonia combines an indigenous heritage, represented by the country's Finnic national language Estonian, with Nordic and German cultural aspects. The culture of Estonia is considered to be significantly influenced by that of the Germanic-speaking world. Due to its history and geography, Estonia's culture has also been influenced by the traditions of other Finnic peoples in the adjacent areas, also the Baltic Germans, Balts, and Slavs, as well as by cultural developments in the former dominant powers, Sweden, Denmark and Russia. Traditionally, Estonia has been seen as an area of rivalry between western and eastern Europe on many levels. An example of this geopolitical legacy is an exceptional combination of multiple nationally recognized Christian traditions: Western Christianity and Eastern Christianity. The symbolism of the border or meeting of east and west in Estonia was well illustrated on the reverse side of the 5 krooni note. Like the mainstream cultures in the other Nordic countries, Estonian culture can be seen to build upon ascetic environmental realities and traditional livelihoods, a heritage of comparatively widespread egalitarianism arising out of practical reasons, and the ideals of closeness to nature and self-sufficiency.

Estonian literature is literature written in the Estonian language The domination of Estonia after the Northern Crusades, from the 13th century to 1918 by Germany, Sweden, and Russia resulted in few early written literary works in the Estonian language. The oldest records of written Estonian date from the 13th century. Originates Livoniae in Chronicle of Henry of Livonia contains Estonian place names, words and fragments of sentences. The Liber Census Daniae (1241) contains Estonian place and family names. The earliest extant samples of connected Estonian are the so-called Kullamaa prayers dating from 1524 and 1528. The first known printed book is a bilingual German-Estonian translation of the Lutheran catechism by S.Wanradt and J. Koell (1535). For the use of priests an Estonian grammar was printed in German in 1637. The New Testament was translated into southern Estonian in 1686. The two dialects were united by Anton Thor Helle in a form based on northern Estonian. Writings in Estonian became more significant in the 19th century during the Estophile Enlightenment Period (1750–1840).

The earliest mentioning of Estonian singing dates back to Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum. Saxo spoke of Estonian warriors who sang at night while waiting for a battle. Henry of Livonia at the beginning of the 13th century described Estonian sacrificial customs, gods and spirits. In 1578 Balthasar Russow described the celebration of midsummer (jaanipäev), the St. John's Day by Estonians. In 1644 Johann Gutslaff spoke of the veneration of holy springs and J.W. Boecler described Estonian superstitious beliefs in 1685. Estonian folklore and beliefs including samples of folk songs appear in Topographische Nachrichten von Liv- und Estland by August W. Hupel in 1774–82. J.G von Herder published seven Estonian folk songs, translated into German in his Volkslieder in 1778 and republished as Stimmen der Völker in Liedern in 1807.

The Learned Estonian Society is Estonia's oldest scholarly organisation, and was formed at the University of Tartu in 1838. Its charter was to study Estonia's history and pre-history, its language, literature and folklore.

The Baltic Finnic or Balto-Finnic peoples, also referred to as the Baltic Sea Finns, Baltic Finns, sometimes Western Finnic and often simply as the Finnic peoples, are the peoples inhabiting the Baltic Sea region in Northern and Eastern Europe who speak Finnic languages. They include the Finns, Estonians, Karelians, Veps, Izhorians, Votes, and Livonians. In some cases the Kvens, Ingrians, Tornedalians and speakers of Meänkieli are considered separate from the Finns.

Gotthard Friedrich Stender, also called Old Stender, was a Baltic German Lutheran pastor who played an outstanding role in Latvia's history of culture. He was the first Latvian grammarian and lexicographer, founder of the Latvian secular literature in the 18th century. In the spirit of Enlightenment, he wrote the first Latvian-German and German-Latvian dictionaries, wrote the first encyclopedia “A Book of High Wisdom on the World and Nature” (1774), and wrote the first illustrated Latvian alphabet book (1787).

Kalevala Day, known as Finnish Culture Day by its other official name, is celebrated each 28 February in honor of the Finnish national epic, Kalevala. The day is one of the official flag flying days in Finland.

Eduard Ahrens was a Baltic German Estonian language linguist and clergyman.

Felix Johannes Oinas was an Estonian folklorist, linguist, and translator.

Runic song, also referred to as Rune song, Runo song, or Kalevala song, is a form of oral poetry and national epic historically practiced among the Baltic Finnic peoples. It includes the Finnish epic poems Kalevala and Kanteletar, as well as the Estonian Kalevipoeg.