In grammar, the genitive case is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can also serve purposes indicating other relationships. For example, some verbs may feature arguments in the genitive case; and the genitive case may also have adverbial uses.

Arabic grammar is the grammar of the Arabic language. Arabic is a Semitic language and its grammar has many similarities with the grammar of other Semitic languages. Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic have largely the same grammar; colloquial spoken varieties of Arabic can vary in different ways.

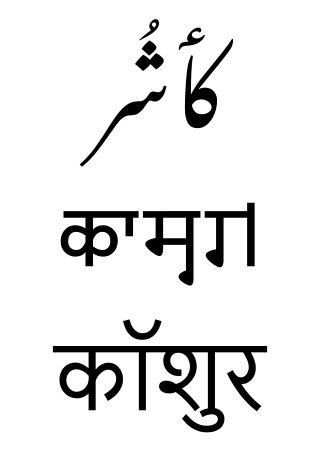

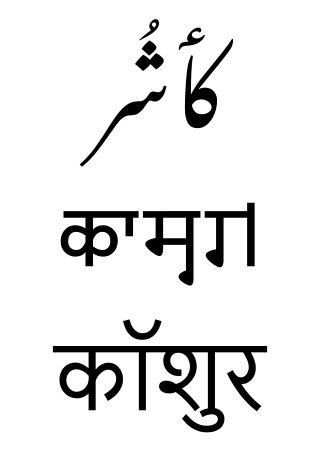

Kashmiri or Koshur is a Dardic Indo-Aryan language spoken by around 7 million Kashmiris of the Kashmir region, primarily in the Kashmir Valley and Chenab Valley of the Indian-administrated union territory of Jammu and Kashmir, over half the population of that territory. Kashmiri has split ergativity and the unusual verb-second word order.

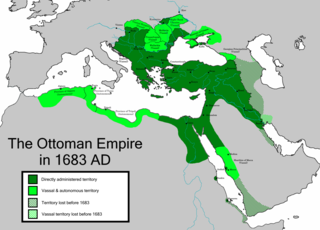

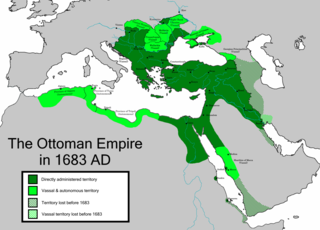

Ottoman Turkish was the standardized register of the Turkish language in the Ottoman Empire. It borrowed extensively, in all aspects, from Arabic and Persian. It was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. Ottoman Turkish was largely unintelligible to the less-educated lower-class and to rural Turks, who continued to use kaba Türkçe, which used far fewer foreign loanwords and is the basis of the modern standard. The Tanzimât era (1839–1876) saw the application of the term "Ottoman" when referring to the language ; Modern Turkish uses the same terms when referring to the language of that era. More generically, the Turkish language was called تركچه Türkçe or تركی Türkî "Turkish".

The Azerbaijani alphabet has three versions which includes the Arabic, Latin, and Cyrillic alphabets.

Wakhi is an Indo-European language in the Eastern Iranian branch of the language family spoken today in Wakhan District, Northern Afghanistan, and neighboring areas of Tajikistan, Pakistan and China.

A possessive or ktetic form is a word or grammatical construction indicating a relationship of possession in a broad sense. This can include strict ownership, or a number of other types of relation to a greater or lesser degree analogous to it.

Yodh is the tenth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician yōd 𐤉, Hebrew yudי, Aramaic yod 𐡉, Syriac yōḏ ܝ, and Arabic yāʾي. Its sound value is in all languages for which it is used; in many languages, it also serves as a long vowel, representing.

In linguistics, a possessive affix is an affix attached to a noun to indicate its possessor, much in the manner of possessive adjectives.

The grammar of the Persian language is similar to that of many other Indo-European languages. The language became a more analytic language around the time of Middle Persian, with fewer cases and discarding grammatical gender. The innovations remain in Modern Persian, which is one of the few Indo-European languages to lack grammatical gender, even in pronouns.

Gilaki is an Iranian language belonging to the Caspian subgroup of the Northwestern branch, spoken in south of Caspian Sea by Gilak people. Gilaki is closely related to Mazandarani. The two languages of Gilaki and Mazandarani have similar vocabularies. The Gilaki and Mazandarani languages share certain typological features with Caucasian languages, reflecting the history, ethnic identity, and close relatedness to the Caucasus region and Caucasian peoples of the Gilak people and Mazandarani people.

Hindustani, the lingua franca of Northern India and Pakistan, has two standardised registers: Hindi and Urdu. Grammatical differences between the two standards are minor but each uses its own script: Hindi uses Devanagari while Urdu uses an extended form of the Perso-Arabic script, typically in the Nastaʿlīq style.

Persian nouns have no grammatical gender, and the case markers have been greatly reduced since Old Persian—both characteristics of contact languages. Persian nouns now mark with a postpositive only for the specific accusative case; the other oblique cases are marked by prepositions.

The Urdu alphabet is the right-to-left alphabet used for writing Urdu. It is a modification of the Persian alphabet, which itself is derived from the Arabic script. It has co-official status in the republics of Pakistan, India and South Africa. The Urdu alphabet has up to 39 or 40 distinct letters with no distinct letter cases and is typically written in the calligraphic Nastaʿlīq script, whereas Arabic is more commonly written in the Naskh style.

Baṛī ye is a letter in the Urdu alphabet directly based on the alternative "returned" variant of the final form of the Arabic letter ye/yāʾ found in the Hijazi, Kufic, Thuluth, Naskh, and Nastaliq scripts. It functions as the word-final yā-'e-majhūl ([]) and yā-'e-sākin ([]). It is distinguished from the "choṭī ye ", which is the regular Perso-Arabic yāʾ (ی) used elsewhere. In Punjabi, where it is a part of the Shahmukhi alphabet, it is called waḍḍī ye with the Gurmukhi equivalent ਏ.

The Pashto alphabet is the right-to-left abjad-based alphabet developed from the Arabic script, used for the Pashto language in Pakistan and Afghanistan. It originated in the 16th century through the works of Pir Roshan.

The Khowar alphabet is the right-to-left alphabet used for the Khowar language. It is a modification of the Urdu alphabet, which is itself a derivative of the Persian alphabet and Arabic alphabet and uses the calligraphic Nastaʿlīq script.

Iḍāfah (إضافة) is the Arabic grammatical construct case, mostly used to indicate possession.

Turkmen grammar is the grammar of the Turkmen language, whose dialectal variants are spoken in Turkmenistan, Iran, Afghanistan, Russia, China, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and others. Turkmen grammar, as described in this article, is the grammar of standard Turkmen as spoken and written by Turkmen people in Turkmenistan.

Hindi-Urdu, also known as Hindustani, has three noun cases and five pronoun cases. The oblique case in pronouns has three subdivisions: Regular, Ergative, and Genitive. There are eight case-marking postpositions in Hindi and out of those eight the ones which end in the vowel -ā also decline according to number, gender, and case.