| Part of a series on the Syrian civil war |

| Syrian peace process |

|---|

Proposals for the federalization of Syria were made early during the Syrian Civil War, [1] were implemented in the mostly Kurdish north and east regions of Syria, [2] and a federalized or decentralised structure was called for by groups in several parts of Syria in 2025. [3] [4]

Contents

- Historical antecedents

- Proposals during the Syrian Civil War

- Timeline

- Post-Assad

- Pro-federalization

- Anti-federalization

- Analysis

- See also

- Notes

- References

- External links

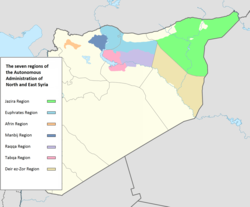

The Rojava conflict led to Kurdish-dominated regions becoming a self-governing federation, Rojava, with a constitution written in 2014, [2] and revised in 2016 [5] and 2023, [6] each time stating that Rojava (Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, DAANES, in the 2023 version) was part of the Syrian state. [6] As of 2016, there was little support for federalization [7] [8] outside of Rojava. [9]

Following the late 2024 fall of the Assad regime, Rojava started negotiations with the Syrian transitional government led by Ahmed al-Sharaa on integration of Rojava with the rest of Syrian state structures, with an eight-point agreement signed on 10 March 2025, [10] and continued intentions for a decentralised national structure. [3]

On 8 August 2025, Druze Sheikh Hikmat al-Hijri and Alawite Sheikh Ghazal Ghazal, speaking via video message, addressed the "Unity of Position of the Components of North and East Syria" conference in al-Hasakah, which brought together about 400 representatives from Syria's minority communities. Al-Hijri called for a national project that transcends narrow sectarian and political divisions, while Ghazal advocated a decentralized system ensuring equality, justice, and genuine participation. Their proposals for decentralized or federal governance were strongly rejected by the Syrian government in Damascus. [11] [12] In late August 2025, Hikmat al-Hijri called for an autonomous Druze region in the Suwayda Governorate in southern Syria and Alawite groups created the Political Council for Central and Western Syria (PCCWS) that explicitly called for a secular, federalised structure for Syria. [4]